I was lying on a dentist’s chair in Germany, recovering from an emergency root canal, contemplating why myths and misinformation spread so easily.

But let me back up.

I had a filling two weeks ago in the United States that was badly botched. The day after I arrived in Germany (where we’re spending our summer), the pain in my tooth reached a crescendo that I had never before experienced. Only shoving cold water in my mouth gave me some respite, and even then, for all of five seconds before the pain came roaring back. Although all of Germany seems to shut down on Sundays, I found a dentist that was open for three precious hours.

Of course, the dentist spoke no English. In high school, I had taken a year of reluctant German, and the dental hygienist’s English was as good (or, I should say, as terrible) as my German. As we tried to figure out what was wrong, we took linguistic liberties to new heights, taking a laissez faire approach to the structures of these two noble languages (Me tooth pain much, ja). After much back and forth that made Tarzan look more like Shakespeare, I was told I’d need a Wurzelkanal. The “Wurzel” part I didn’t get, but the “kanal” part came through loud and clear.

Trending: Best Happiness Books of 2025 (So Far)

I had never had a root canal before, but its reputation preceded itself. I thought most people ranked root canals right up there with a colonoscopy. As the hygienist began to pull out the tools that would probe the depths of my tooth to excise a nerve, my nerves began to rattle.

What followed was shock and awe. Not at the pain, but at the lack thereof. Aside from the minor sting of the anesthetic injection, I felt zero pain during the procedure. The only pain I experienced was the one that preceded and required the treatment, not the treatment itself.

I strolled back to our apartment, numb and slurring like a sailor on leave, wondering how I bought into this myth of the painful root canal, and why, in general, misinformation proliferates.

We’re eager to believe myths in part because they appeal to our emotions. Given a story and a mountain of data, the story prevails. Stories resonate. Stories sell. These mentally vivid images strike a deep, lasting chord, known as the narrative fallacy. We remember what so-and-so told us about how his male-pattern baldness was caused by too much time in the sun. We fall for the story, throwing logic and skepticism to the wind.

Myths also feed our appetite for drama and scandal. They force us out of our 9-5 hamster wheels, the humdrum nature of our daily routines. It’s far more interesting to contemplate the possibility of alien sightings and abductions than to listen to a scientist drone on about the shoddy nature of the supporting evidence.

Trending: Why Rest is the Biggest Productivity Hack for Your Brain

The media is in part to blame. It lends credence to these incredulous claims by giving them air time, making it difficult for the public to distinguish scientific fact from fiction. A mountain of data dispelling the fraudulent study that links the MMR vaccine to autism isn’t interesting. Jenny McCarthy explaining how her son developed autism after getting a vaccine (and then being miraculously cured through a dietary intervention) is endlessly fascinating.

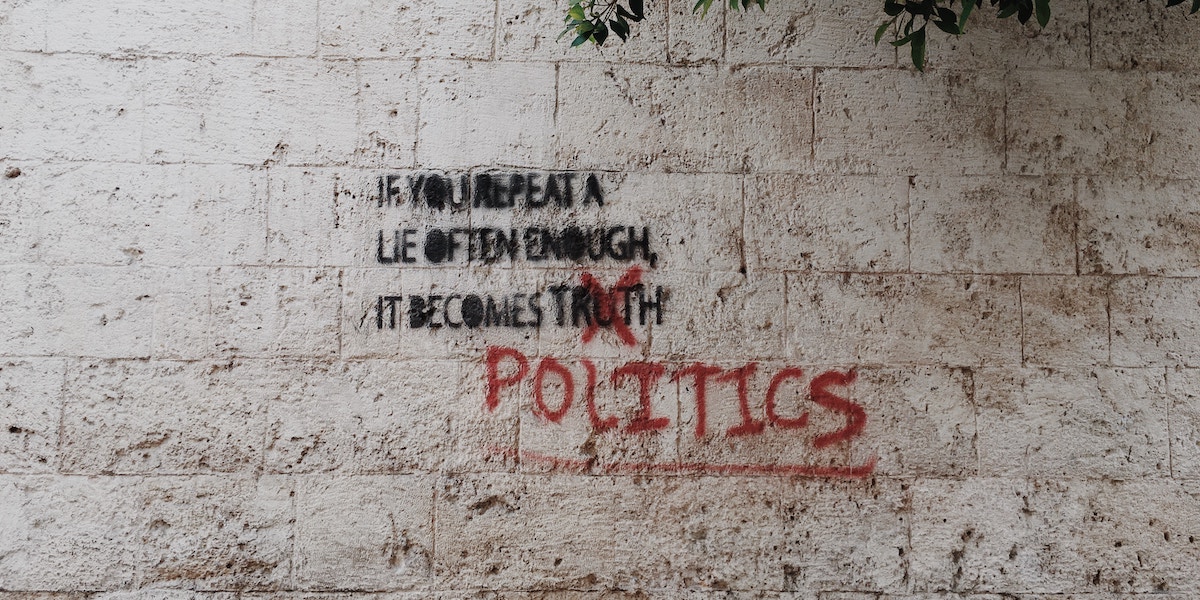

Once reported and retweeted, these myths become the truth. As Tali Sharot observes in her book, The Influential Mind, “by repeating the myths regarding the MMR vaccine in an attempt to dispel them, people sometimes wind up remembering the myths rather than the counterevidence.”

Myths persist also because they fill the gaps in our understanding. They create order out of chaos, clarity out of complexity, and a cause-and-effect relationship out of blind luck. Your child exhibits signs of autism? Blame it on that vaccine he got two weeks ago. You spotted a human face on Mars? Obviously the elaborate work of an ancient civilization that, coincidentally, also helped the Egyptians build the pyramids of Giza.

The search for certainty over uncertainty, the preference for stories over data, these are human tendencies that help us make sense of the world. But they also lead us astray. The antidote is also human: tapping into our ability to question and doubt everything from emotional appeals to confident political claims. It’s only through the relentless exercise of our critical-thinking muscles that myths and misinformation can be exposed for what they are.

Trending: How to Break Free From the Ambition Trap

Ozan Varol is a rocket scientist turned award-winning author and law professor. For additional content like this, check out his blog, the Weekly Contrarian.