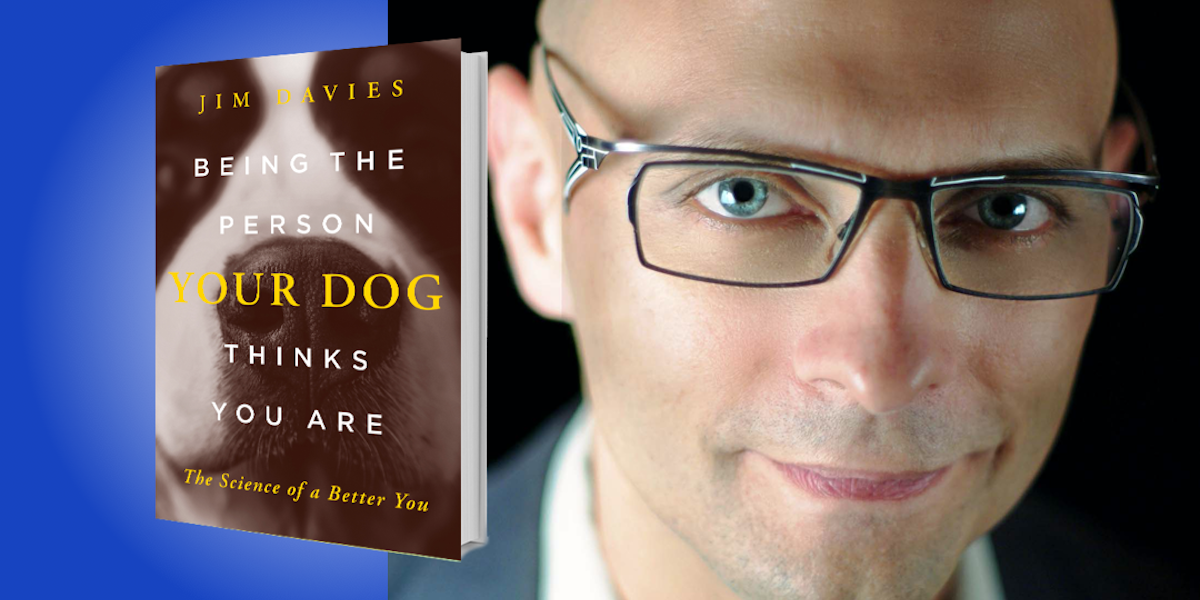

Jim Davies is an associate professor in the Institute of Cognitive Science at Carleton University. Director of the Science of Imagination Laboratory, he explores processes of visualization in humans and machines and specializes in artificial intelligence, analogy, problem-solving, and the psychology of art, religion, and creativity. His work has shown how people use visual thinking to solve problems, and how they visualize imagined situations and worlds.

Below, Jim shares 5 key insights from his new book, Being the Person Your Dog Thinks You Are: The Science of a Better You. Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Turn good advice into a habit.

You’ve probably already gotten some great advice in your life, so why do you still have so many problems? One reason is because just about none of the things that make your life better work simply by learning what they are. To create any lasting benefit, you have to change your habits.

Many people try to use willpower to build new habits or override old habits, but this is not a very effective strategy on its own, because some days you just won’t have the willpower—you’ll be stressed out or distracted, and when the conscious part of your mind is thinking about something else, existing habits take over. Instead, you need to devise strategies that consistently foster repetition and reward for the desired behavior. So when you hear some good advice about how to improve your life, remember that it’s not enough to know it—you have to turn it into a habit.

2. The best thing you can do for your productivity is to reduce distraction.

If I had to suggest one thing to make a person more productive, it would be to reduce distraction so that you can allocate more time for concentrated work. The easiest way to do this is to turn off the notifications on your phone for as many apps as you can. It seems like every app you download asks you if it can send you notifications. Every time I get that prompt, I imagine it saying, “May I have permission to lower your productivity so that my company can make more money?” When you think of it that way, it’s a lot easier to say no.

“Turn off the notifications on your phone for as many apps as you can.”

3. Trust your instincts, but only sometimes.

Sometimes your instincts are spot on, and sometimes they’re not. So how do you know when you should trust your instincts, or when you should instead override your instincts with science or data or careful reasoning? Of course, every situation is a little different, but one rule I try to follow is this: Trust your instincts when reacting to a situation that is similar to one that our ancient ancestors might recognize—the time before industry, before computer technology.

In those situations, your instincts might be really good. Do you smell something off about the meal sitting in front of you? Maybe you shouldn’t eat it. Maybe you smell something fishy about a deal somebody is offering you, and you don’t trust them. Pay attention to your feelings. But if the situation is totally new in a historical sense, then you need to put your intuitions aside and pay more attention to reasoning and data.

4. To be the best person you can be morally, look beyond the industrialized world.

When you’re helping somebody or hurting somebody right in front of you, it feels very visceral—you get a guilt feeling or a good feeling. But if you’re doing something for people far away, it can feel detached and cerebral, and it sometimes doesn’t even feel like a moral decision at all. And since most people make moral decisions by responding to how they’re feeling about this or that situation, our moral focus tends to be on the people we meet. But did you know that you can give someone in Southern Africa a year of life for about 70 U.S. dollars, and you could save someone’s life for about five grand? There’s very good science behind these numbers—this is not just charities boasting. It’s far cheaper than saving lives in the industrialized world, no matter which charity you pick.

“You can give someone in Southern Africa a year of life for about 70 U.S. dollars, and you could save someone’s life for about five grand.”

In terms of time and money, there is no more efficient way to be a good person than to save the lives of people threatened by malaria. So if you donate a few hundred dollars a year to an effective charity, like the Against Malaria Foundation for example, you will probably be a better person than anyone you know.

5. Some things matter a lot—and some things matter much less.

You often hear advice about health and happiness and productivity, but there’s rarely any talk about how effective it is. How much of an effect is this really going to have? That part is crucially important; whether it comes to environmental protection or making yourself less stressed or getting more work done, some things matter so little that they are not worth your attention.

One example comes from the science of maintaining your personal happiness. The most important thing you can do to make yourself happier, assuming you aren’t dealing with a mental illness or something that requires special attention, is to spend time with people you care about. Even introverts benefit from this enormously. Not only is it the best thing for your happiness, but it’s also the best thing you can do for your health. In terms of extending your life, it’s even more effective than regular exercise and quitting smoking!

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: