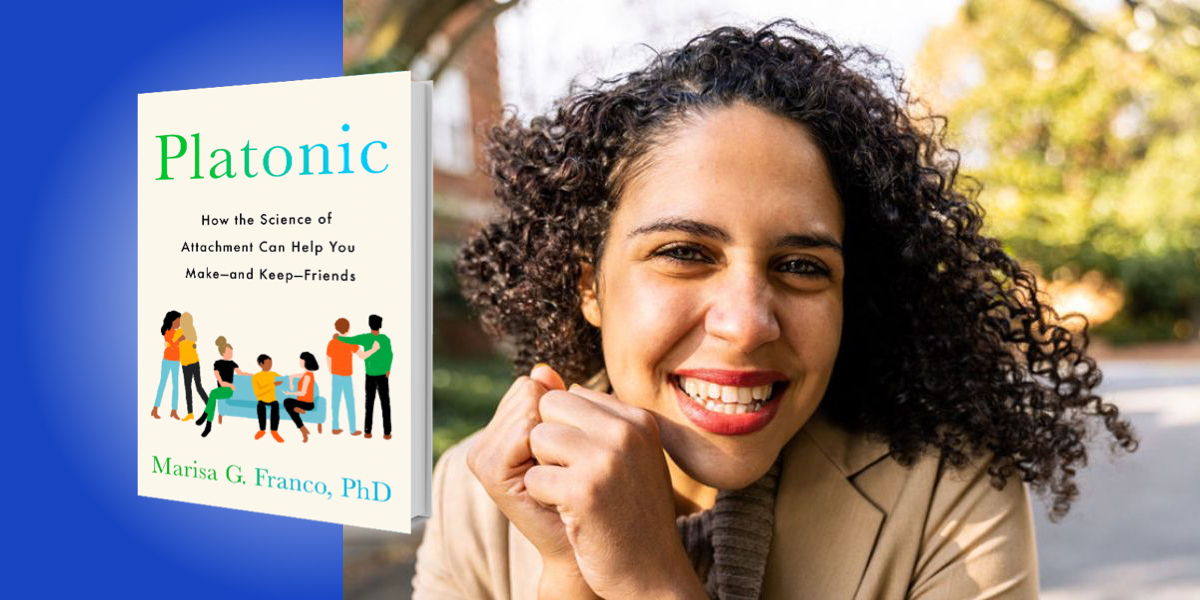

Dr. Marisa G. Franco is a professor, speaker, and psychologist. She is an Assistant Clinical Professor at the University of Maryland, where she teaches courses about loneliness and friendship. She writes for Psychology Today and she has been a featured psychologist in The New York Times, NPR, and Good Morning America.

Below, Marisa shares 5 key insights from her new book, Platonic: How the Science of Attachment Can Help You Make—and Keep—Friends. Listen to the audio version—read by Marisa herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Friendships don’t happen organically—you have to initiate.

There is a misconception that friendships happen organically because when we were kids they did. This is the case because, according to sociologist Rebecca Adams, friendships happen organically when we have continuous, unplanned interaction and shared vulnerability. If you see someone every day, then you tend to let your guard down over time. It’s common for kids to connect during recess, lunch, and gym on a daily basis.

As adults, we don’t inhabit those same environments. We might see colleagues every day at work, but that doesn’t mean we have shared vulnerability. Adults often don’t let their guard down around colleagues. One study found that the more time we spend with colleagues at work, the less close we feel to them. This suggests that adults need to make more of an effort than children have to in order to make friends. This might look like telling someone, “Hey, it’s been such a pleasure connecting. Would you be open to exchanging contact information?”

“Adults need to make more of an effort than children have to in order to make friends.”

According to one study, people who thought friendship happens effortlessly grew increasingly lonely over time, while people who saw friendship as something that requires effort grew less lonely as the years went by. So, you’re going to have to go out there and try.

2. Don’t expect rejection.

Our brains have a negativity bias because we learn more from negative information than from positive information. For example, a friend told me that in sixth grade one of her friends told her, “None of us like you.” From then on, she never initiated interactions with friends again. There must be many instances in which people have wanted to be her friend (myself included) and would have liked for her to initiate more, but because of that one instance of rejection, she assumed that everybody would reject her. This phenomenon is called the liking gap. Researchers had strangers interact and then asked them, “How much do you like one another?” They found that participants consistently underestimated how much they were liked by others. The more self-critical a person is, the more pronounced their liking gap.

I took this research to heart on a recent solo trip to Mexico City. I knew people are less likely to reject me than I think so I encouraged myself to connect with people. I was at a coffee shop and noticed someone speaking American English, and I said to him, “Where are you from?” We got to talking and then I asked him to exchange contact information by saying, “Oh, it was so great talking to you. I’d love to stay connected.” Then I invited him to a language exchange group that night which I knew about through meetup.com. That’s how I made friends while traveling solo abroad. I initiated, knowing that people are less likely to reject me than I think.

3. Assume that people like you.

This is hard. Our brain tends to assume the opposite because of negativity bias—it’s just trying to help us survive, but let’s face it, sometimes our brains get a little bit in the way. Research finds that some people are high in rejection sensitivity, meaning they project that they’re going to be rejected onto ambiguous circumstances, like if a friend doesn’t sit next to them or respond to their text right away. What happens is these rejection-sensitive people tend to reject others. They become cold and withdrawn because of the rejection they think they’re enduring. After they reject others, people reject them back.

“When we assume rejection, this triggers behaviors that make rejection more likely to become true.”

Researchers found that when they lied to people and told them, “Hey, you’re going to go into this group and, based on your personality profile, we assume that you’re going to get along with these people and that they’re going to like you.” Telling people this made the participants warmer, friendlier, and more open. This phenomenon is called the acceptance prophecy. When we assume people like us, it triggers behaviors that make this more likely to become true. When we assume rejection, this triggers behaviors that make rejection more likely to become true. People are less likely to reject you than you think, and it helps to assume that people like you.

4. Find a group that meets repeatedly over time.

This is a life-changing tip that motivated me to write Platonic. I was feeling grief after bad breakups in my young twenties, so I met up with my friend, Heather, and I was like, “I think what would really help me heal is if we started a wellness group with our friends. We can meet up each week, meditate, cook, do yoga.” Heather said yes, and that was the start of our wellness group. Every week we practiced wellness together and it felt transformative. The most healing part wasn’t the activity of the week, but just being around friends and having a regular sense of community.

You can start your own group to create something repeated over time that generates community, or you can think of other ways to engage in what interests you with other people. If you like learning languages, don’t take a language workshop, take a language class. Or if you like improv, take an improv class that meets repeatedly over time. When we see people repeatedly, it creates a connection.

For example, researchers placed random women into a large psychology lecture for varying numbers of classes—some for none of the classes, others for most of the classes. At the end of the semester, they asked the students, “Do you remember any of these women?” And the students said, “No.” But yet, when asked, “How much do you like each of these women?” the students, even though they didn’t remember any of the women, reported liking the woman that had shown up to the most classes 20 percent more than the woman that had not shown up to any classes. This suggests that the exposure effect happens completely unconsciously. We come to like people more when we see them over and over again, even if we don’t engage with them.

“People prefer someone that makes them feel valued and loved, rather than someone particularly entertaining or charismatic.”

This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. If you see someone repeatedly and they don’t pose a threat, your brain says, “Chill, you can trust them, you can become friends.” This also means that you should expect that early interactions with a new person will be awkward. Your brain is still set to weary mode when you don’t know a person too well. Over time, you will feel more comfortable. Don’t quit after one time. To create connections, show up repeatedly.

5. Make other people feel like they belong.

When I was in college, I thought to be an attractive friend to others I had to be smart, funny, charismatic, and insightful. My plan was to be magnetizing and people would flock to me. I now realize that people prefer someone that makes them feel valued and loved, rather than someone particularly entertaining or charismatic.

In fact, people reported that the number one quality that they look for in a friend is someone who makes them feel valued. According to risk regulation theory, we decide how much to invest in a relationship based on the discernment of our likelihood of rejection. So, when people tell us, “You’re not going to be rejected here,” we feel safer investing in that relationship. The people that are best at making friends are really good at making other people feel comfortable.

To listen to the audio version read by author Marisa G. Franco, download the Next Big Idea App today: