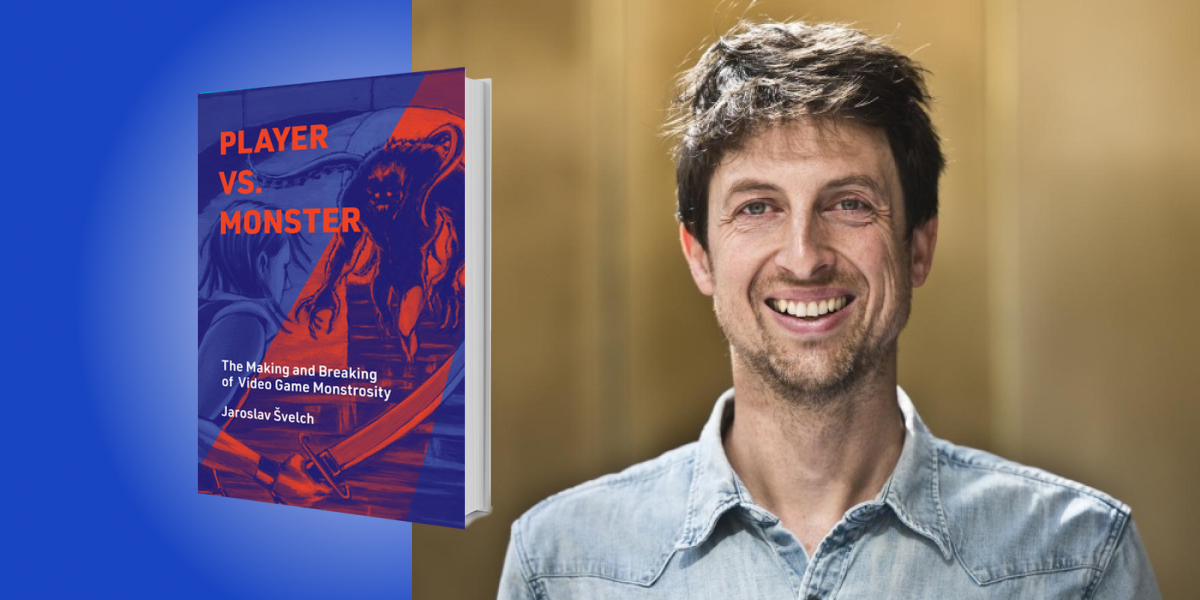

Jaroslav Švelch is based in Prague at Charles University and also teaches at the game design department of the Academy of Performing Arts.

Below, Jaroslav shares five key insights from his new book, Player vs. Monster: The Making and Breaking of Video Game Monstrosity. Listen to the audio version—read by Jaroslav himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Monsters are simulated.

Over the years, monsters have become a staple of video games, posing as enemies to beat and obstacles to overcome. Very often, these monsters are borrowed from film, literature, and comics; one can fight zombies, dragons, demons, aliens, and so on. But there is one important difference between monsters in traditional media and monsters in games; the latter are simulated and follow predefined rules.

In a book, the monster can be hinted at with a vague yet creepy description; in a film, we can catch a glimpse of a monster and speculate about the details. In a game, however, we encounter it again and again. We play with it to learn its moves and find its weak spots. In general, this makes video game monsters less mysterious, and it also explains why it’s so difficult to adapt horror fiction into video games.

2. Monsters present a paradox to the player.

The function of the monster in culture is to give shape to the fears and anxieties of individuals and society. The function of the monster in games is to serve the player’s experience of agency (with some exceptions). Even the creepiest monsters are there for us to beat. This creates a paradoxical task for video game designers: how to make monsters that fill us with fear and awe, even if we know they can be beaten, and if the fear and awe go away quite quickly?

“The function of the monster in culture is to give shape to the fears and anxieties of individuals and society. The function of the monster in games is to serve the player’s experience of agency.”

Game designers are aware of this issue, and try to impress us with boss monsters who are often bigger, more powerful, and visually impressive. Although boss monsters might seem impossible at first, even they can be beaten if you spend long enough figuring them out.

3. How Space Invaders changed arcade games.

Before the 1970s, there were few, if any, monsters in games. Think of chess, card games, board games, or sports. The practice of using monsters as opponents only took off in the 1970s, after the launch of the original tabletop Dungeons & Dragons in 1974 and Space Invaders in 1978. This was the beginning of what we now call the “player versus environment” gameplay. Space Invaders, specifically, presented a new paradigm of how monsters were used in shooting games. Before Space Invaders, there were shooting galleries and electromechanical shooting games but, in these situations, the worst thing that a target could do to you was not get hit.

The aliens in the 1978 Space Invaders game could, on the other hand, kill your avatar—your embodiment in virtual space. This innovation brought about gripping and intense gameplay, and made shooter games incredibly popular.

4. The trivialization of monsters allows us to kill them without remorse.

Following the success of Dungeons & Dragons and Space Invaders, monsters became the go-to video game antagonists. There are many good reasons for that. Firstly, they were already popular thanks to monster movies and comics. Secondly, slaying monsters is a prototypical element of a heroic story, and lastly, perhaps most importantly, it’s morally acceptable to kill monsters.

“The ease with which we kill monsters suggests that all our fears and problems can be destroyed with strength or firepower.”

Interestingly, the designer of Space Invaders, Tomohiro Nishikado, originally intended to use human opponents, but he decided that it would be unethical to shoot them. It’s less controversial to have the player kill monsters rather than people, but at the same time, this role of a default enemy has trivialized monstrosity. It presents a simplified view of otherness, according to which whole classes of beings are defined as expendable. The ease with which we kill monsters suggests that all our fears and problems can be destroyed with strength or firepower. This feels especially outdated at a time when humanity faces incredibly complex challenges like climate change and global pandemics.

5. Monsters can be used creatively.

Some games break the mold and question the idea that monsters can simply be killed for pleasure. Titles like Shadow of the Colossus undermine the heroism and hubris of the monster-killer. The game’s protagonist is a tragic hero who slays huge but peaceful colossi and eventually becomes a monster himself. Some games make monsters sympathetic, like Undertale, a game where you can kill monsters in the usual way, but you can also take a “pacifist” route—although it is much more difficult. Additionally, there are games where monsters are invisible, inscrutable, or otherwise out of reach—in the Amnesia series, for example, the player’s avatar loses sanity when it looks at monsters.

All in all, video games and their monsters have immense potential to make us rethink our relationship with otherness and question our anthropocentric hubris.

To listen to the audio version read by author Jaroslav Švelch, download the Next Big Idea App today: