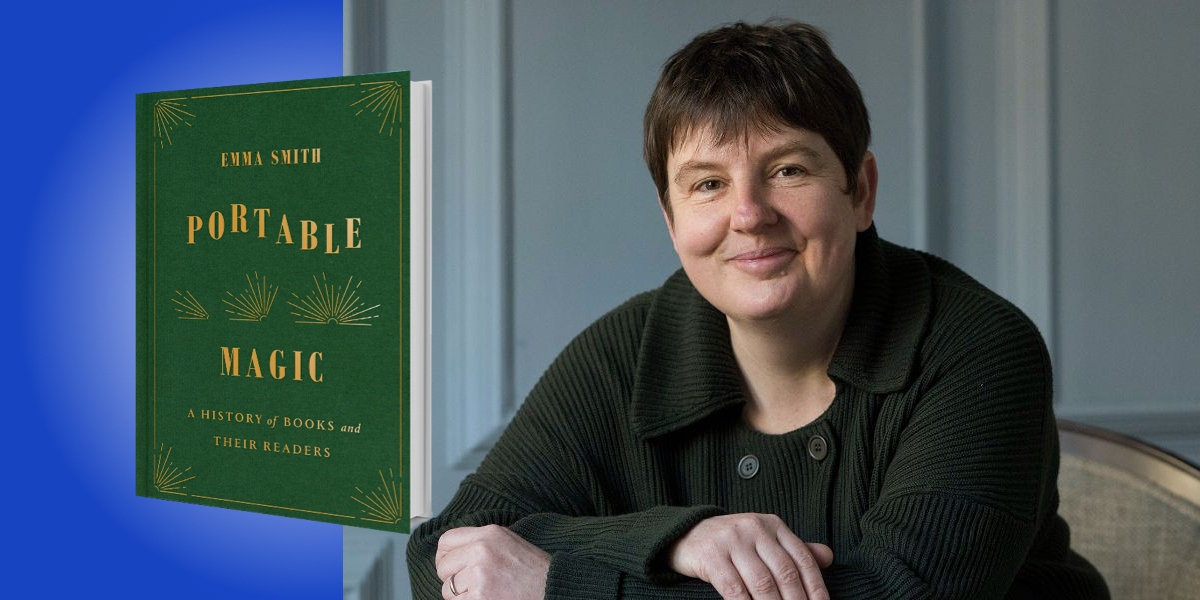

Emma Smith is a professor of Shakespeare studies at the University of Oxford, and a fellow at Hertford College. Below, she shares 5 key insights from her new book, Portable Magic: A History of Books and Their Readers. Listen to the audio version—read by Emma herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Books are a remarkable technology.

When we think about books and technology, we often think of digital books and eReaders. But books with physical pages, a spine, and protected by a cover are an amazing reading hack.

Back in the first Christian century, the Roman poet Martius gave a cheeky advert for books as a new reading format: they are much handier than scrolls, easier to carry around, and take only one hand to operate. Just as we’ve learned to swipe and pinch screens, so our ancestors, who were used to scrolling horizontal strips of parchment (animal skin or plant fiber like papyrus), had to learn to flick pages, use their fingers to mark their place, and rub the corner of the page to turn it.

Those earliest books are entirely recognizable today. If you swapped Portable Magic for the gospel book buried with St. Cuthbert in the seventh century or the first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, all readers across time would be familiar with the artifact and how to use it.

We sometimes worry that eBooks will eclipse paper books, but the real issue is how similar they are. eBooks are the same size, format, and try to mimic the same techniques. They are often called something like “paper white” to emphasize their aspirations to be a book. Remember how Pinocchio wanted to be a real boy—well, eBooks want to be real books.

2. You can’t always judge a book by its cover.

Millions of publishing dollars are spent on book covers each year, although that wasn’t a standard part of publication until the second half of the twentieth century. Many readers have favorite covers and can hardly read a new edition of a much-loved title because it doesn’t have the preferred cover. Sometimes it comes down to personal taste, but other times there’s a creative mismatch between what the book looks like and the content inside.

“A series of abolitionist gift books hijacked a format that was thought sentimental and harmless, and used them to publicize the moral outrage of slavery.”

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, as gift-giving was becoming an important part of Christmas, books were marketed as the ideal holiday gift. Top of the wish list were specially designated gift books or annuals—these had names like Forget Me Not, or The Garland—which were beautifully produced, with colored silk and satin covers, full of poems and engravings, and they were advertised as the perfect gift for women. Women could give them to other women, and it was a gift that a man could give a woman without implying marriage. They were hugely popular.

With these popular books came some snootiness—one of the bonehead suitors in George Eliot’s novel Middlemarch is shown to be hopeless because he believes that a copy of Forget Me Not is a suitable present for an intelligent woman. But the women who exchanged these books had the last laugh. A series of abolitionist gift books hijacked a format that was thought sentimental and harmless, and used them to publicize the moral outrage of slavery. An abolitionist group in Boston produced Autographs for Freedom, which looked like a gift book, circulated as such, and its revolutionary content went under the radar.

3. Books carry an almost sacred aura.

The first books were bibles. The word bibliography, or the French word for library, bibliotheque, clearly overlap with the term bible. Christianity and the book developed hand in hand, and although three major religions claim to be religions of the book, book technology is most closely associated with Christianity. The torah in a synagogue is still in scroll form; the Koran is most often transmitted orally by learning its verses by heart.

I love that when we meet the grizzled Luke Skywalker in the last of the Star Wars films, he is on an island with the library of Jedi scriptures—a set of blue and gold, leatherbound books. Most of our books today do not carry sacred content, but nevertheless, I suggest that all books have retained some of that sacred aura they had at the very beginning. That’s why we often find damage to books emotionally difficult, and why burning books is such a red button subject. A man on Twitter who cut a fat modern novel in half (existing in hundreds of thousands of editions, so not at all valuable) in order to have a lighter commute was more or less put in a police protection program and given a new identity as a result of the backlash.

“Most of our books today do not carry sacred content, but nevertheless, I suggest that all books have retained some of that sacred aura they had at the very beginning.”

Books rouse the passions. Everyone has an opinion, for instance, on people writing in them, folding down the corners, arranging them by color, throwing them away after they’ve finished reading them, dropping them on the floor, or bending their spine. If any of these make you wince, maybe you’re subconsciously thinking of those bibles.

4. The form of a book is part of its meaning.

You may feel that the book itself is just a container for the far more important bit—the words, ideas, and information within. That’s partly true because their form affects their meaning.

When Shakespeare’s plays were published after his death in a big, formal volume called the First Folio, the publishers were saying something about how they wanted these works received through the manner of publication. Instead of the cheap, topical, popular form of the theater, they released an expensive book, made to last and to occupy space in a library where it could be studied seriously—a work, rather than a play.

Something similar happens to more ordinary books too. Paperbacks were the baby boomers of post-war publishing, when stuffy hardback titles were superseded by modern, cheaper paperback ones. Unsurprisingly, the kinds of works published in paperback were themselves part of new attitudes: Dr. Spock’s Baby Care, Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People, Tolkien’s The Hobbit—the appeal of these works was partly the fresh format that chimed with their countercultural ideas. There’s a reason the Beatles didn’t make a song called “Hardback Writer.”

“Instead of the cheap, topical, popular form of the theater, they released an expensive book, made to last and to occupy space in a library where it could be studied seriously—a work, rather than a play.”

Sometimes the overlap of form and meaning can be taken to extremes. Ben Denzer is an American artist whose works are often in book form. For instance, he made a little square yellow book called “American Cheese” made of 20 squares of plastic wrapped cheese. That is a book in which form and meaning are identical. But perhaps Denzer is asking what is a book, what might it mean to consume a book, and is anything that has turning pages and a spine and a cover a book?

5. You can never truly get rid of a book.

I don’t just mean that it’s hard to give away books to thin out a bookshelf. It’s funny how having lots of books—more than you could read in the rest of your life—makes a person seem like an intellectual, whereas having more shoes than you can wear or cars than you can drive makes you seem needy or overcompensating.

Books are a part of our lives, witnesses to particular moments, friendships, enthusiasms, ambitions, and versions of ourselves. As forensic science teaches, every contact leaves a trace. There are projects harvesting premodern DNA from dust in the gutter (that channel between the pages) of old books. Readers leave part of themselves in the books, just as the ideas and possibilities from the books remain with us, too.

I love, with a kind of mournful curiosity, reading inscriptions in books at the second-hand shop: professions of affection from a relationship that is presumably over. We all leave our mark on books, be that visibly or invisibly. Books and humans have a long and symbiotic history. We can never really get rid of them.

To listen to the audio version read by author Emma Smith, download the Next Big Idea App today: