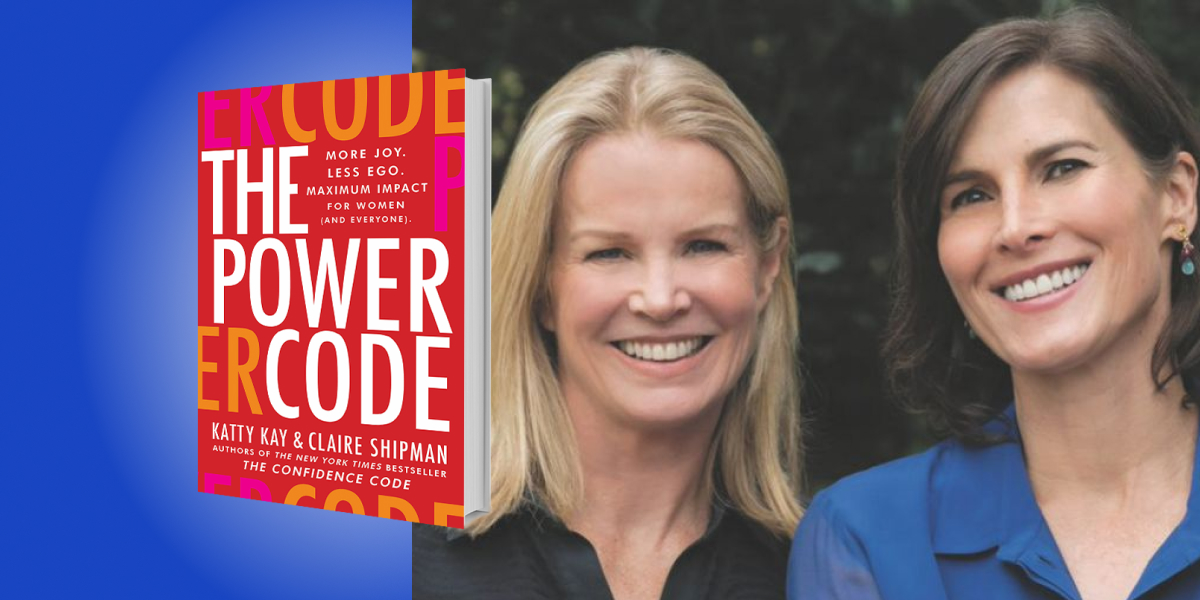

Katty Kay and Claire Shipman are journalists based in Washington D.C., who have extensively covered the White House, elections, wars, and financial collapses, among other front-page political spotlights. This is their third book together.

Below, Katty and Claire share 5 key insights from their new book, The Power Code: More Joy. Less Ego. Maximum Impact for Women (and Everyone). Listen to the audio version—read by Claire—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Women don’t want power—at least, not the current version.

There is a disturbing amount of data that suggests women don’t like power all that much. And perhaps with good reason because research shows that, for women, the costs of getting power are too high and power itself isn’t that appealing. At least, that’s what many women feel about power in its current form. This finding may help explain why only 10 percent of CEOs at Fortune 500 companies are women and only 27 of the 193 countries in the world are led by women.

The problem isn’t women. Women have all the qualities and qualifications to wield power effectively and with great impact. Women are better educated than men in an economy that values brains over brawn. Multiple global studies show corporations perform better, with higher profits, when they employ more women in leadership. The problem is power as it is currently conceived.

2. Women and men define power differently.

Through the centuries, the traditional understanding of power (defined by the men who wielded it) was of a hierarchical force. But our research shows that women tend to have a different interpretation of power. Men’s notion of power infers control over and competition with other people, perhaps because they tend to be more hierarchical and higher in social dominance than women. It’s a zero-sum proposition: more power for me means less for you, and vice versa.

“Power for women can be a win-win.”

Women don’t tend to see power in such finite terms. We can both have power and be collaborative, precisely because we see it as non-zero-sum. Power for women can be a win-win. If this kind of power was embraced, it would create different organizations, cultures, and operating styles—even different outcomes. This isn’t just an exercise in redefinition, it’s about reimagining what kind of power gets noticed, emulated, and rewarded. It’s about changing existing dynamics that clearly aren’t suited to women’s purposes.

3. Power does stuff to our brains.

In 1887, Lord John Acton, the English politician and writer, came up with the immortal phrase, “Power tends to corrupt, absolute power corrupts absolutely.” A century and a half later, Acton’s premise still intrigues neuroscientists. The study of how power affects the brain is in its infancy, but it has already brought forth provocative new ideas—ideas that both reinforce and contradict Acton’s theory.

Power does tend to encourage less empathy, but it also encourages taking action and liberates a person to be more authentic. In fact, power is a tool; it’s almost neutral and in the right hands, and it can have very positive effects. We uncovered research that suggests that women who do rise to the top are less likely to be corrupted by power, maintaining empathy and connection to the lower ranks.

You can prime yourself for power. Before a big job interview, or any other important event, set aside 15 minutes to remember a time when you felt powerful. For example, a time when you were influencing others to make a change. Spend at least five minutes writing about it, on paper, to help retrieve the memory. Note how you feel as you go about this challenge. Studies show the effort of this exercise can last all day, and, over time, it can become habit-forming. Studies have shown that in real interviews, those who were primed for power had better outcomes.

4. Power still involves pots and pans.

We don’t usually write about marriages. Confidence, science, diversity, economic policy—we’ve tackled all that. But as we researched power, we realized we couldn’t ignore what happens at home. Often, the biggest barrier to women getting power isn’t bosses—it’s husbands. We say husbands rather than partners because research shows that it’s in marriages between a man and a woman that these barriers continue to be the most immutable.

“Often, the biggest barrier to women getting power isn’t bosses—it’s husbands.”

A woman with a job does more housework than a man who doesn’t work. It’s not just doing the physical work that takes so much time. It’s the planning, too, known as cognitive labor. At work, this is a highly paid skill. Anticipating an issue, identifying it, deciding what to do, and monitoring the outcome. The same skill set for organizing a kid’s soccer camp is used to set up a conference. Women handle the bulk of cognitive labor at home.

While women may fantasize about a husband who does more housework or stays at home, they protect the status quo as well. One-third of American women earn more than their husbands, and that number grows every year. But in couples where that’s the case, they often lie about it on the U.S. Census form to make it look like the man is earning more. Both the husband and the wife will misreport their incomes to make it look like a traditional marriage.

5. Men may seem to be clinging to power unfairly; it’s important we use a different lens.

Humans hate loss. It’s known as loss aversion theory. Whether it’s something as small as a sweater or as big as power, we fight hard to keep what we have. It’s critical to consider the reaction men may be having to their loss of power, in scientific terms. It helps us empathize with them and that might ease the power transition.

And what men have, as ardently as they may fight to keep it, isn’t that great. They are pushed by society, by spouses, to keep playing the outdated role of primary breadwinner, which is why the number of stay-at-home dads has barely grown in a quarter of a century. Some men realize the zero-sum power formula isn’t working. One law partner told us, “Men get sucked into our careers and the demands. We find it hard to say no or to say we’ve had enough. We don’t love it, but we don’t have a different road map.” One man who quit his job told us he had a voice in his head reprimanding him for failing at the one thing he was supposed to do in life: earn an income. How sad is that?

Men are missing out on a whole range of life’s richer pleasures, like the satisfaction of caregiving, because they still feel they must be “real” men. Belgian sociologist Isabelle Roskam has found that, in general, women are more prepared to cope with the stress and exhaustion of balancing domestic and work duties. But not naturally so. From a young age, girls imitate women, and boys imitate men. Boys are particularly resistant to imitating behavior not typical of their gender. Roskam says it’s urgent that boys are given more chances to see themselves as fully engaged dads and as emotional beings.

To listen to the audio version read by co-author Claire Shipman, download the Next Big Idea App today: