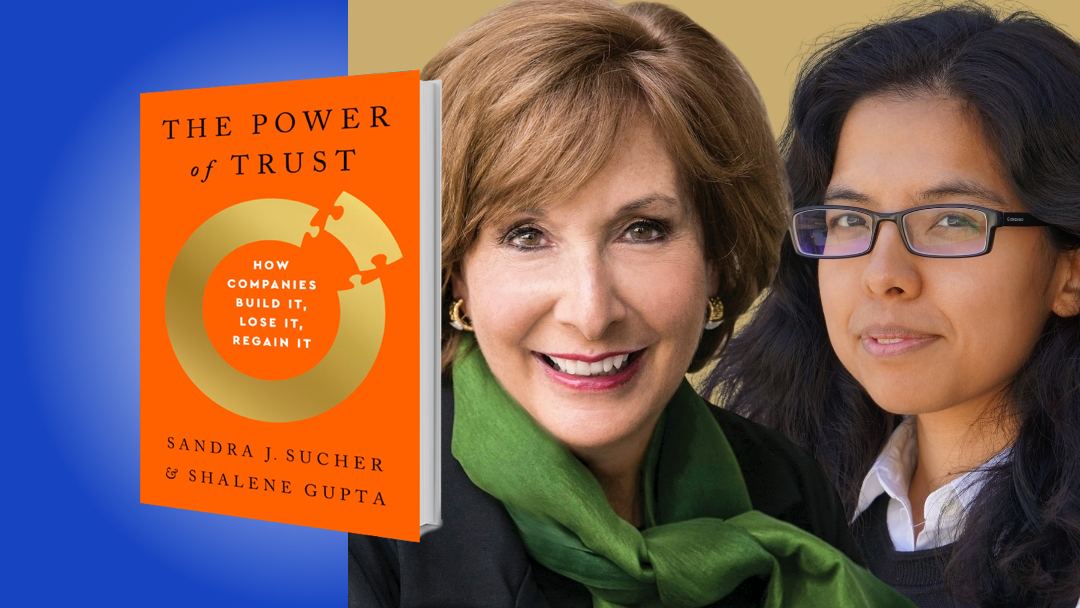

Sandra Sucher is a professor of management practice at Harvard Business School, and Shalene Gupta is a research associate at Harvard Business School. Prior to academia, Sucher was a business executive for 20 years, having sat on the executive board of Fidelity Investments. Gupta came to Harvard after being a business technology journalist for Fortune, as well as earning many other achievements and grants, such as the Fulbright Scholarship. Their book draws on two decades of research from which they have discovered practical advice on how to build long term trust and pursue moral leadership.

Below, Sandra and Shalene share 5 key insights from their new book, The Power of Trust: How Companies Build It, Lose It, Regain It (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version of the book bite—read by the authors themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Trust is a relationship based on vulnerability.

When we trust, we give people and organizations power over us, trusting that they will not abuse this power. Often, we take this trust for granted and don’t even realize that we are trusting— like when we get on a plane believing that it will take us from point A to point B without crashing. We have no ability to check whether the plane will work, and take it on faith that we are safe. Then when we hear about disasters like the crashes of Boeing’s Max 737 jets, we start asking questions about how the planes were designed.

When we learn that Boeing designed the Max 737s with the assumption that pilots could respond to a software malfunction within four seconds, and that the company refused to require pilots to be trained on the new system in order to cut costs, we know that we’ve been betrayed. Boeing abused trust by using a flawed design that ended up killing 346 people.

Trust is a special form of dependence, and is based on the idea that we are vulnerable to others’ power when we trust them.

“Competence alone is not enough.”

2. There are four different elements to trust.

We trust in four different dimensions: competence, motives, fairness, and impact.

Competence is our ability to do something. It’s foundational for building other types of trust. For example, we became enamored with Uber because it offered an efficient and convenient way to get a ride, and was often cheaper than a taxi. However, competence alone is not enough. There’s a lot about Uber to feel queasy about.

In 2013 an Uber driver ran over a little girl. The family sued, but Uber refused to protect the driver saying that the accident happened when he was not taking any rides. As a result, we began to question Uber’s motives. How much did Uber actually care about the family or the driver?

Meanwhile, between 2013 and 2015, Uber had booked and cancelled 5,000 rides on Lyft. Now we had questions about Uber’s fairness: how did it treat employees and competitors?

Then in 2017 a former employee, Susan Fowler, published a blog post about Uber’s toxic work culture where sexual harassment went unpunished. Consequently, by the time Fowler left the company, the percent of women in her division dropped from 25% to 6%.

It’s no surprise that as the public lost confidence in Uber’s motives, means, and impact, Uber started to lose market share to its competitor, Lyft. In January 2021, Uber’s market share had fallen from 90% to 68%, while Lyft’s had climbed to 32%.

3. Trust is built from the inside out.

We tend to think that trust is an exercise in managing reputation. In reality, trust is built from the inside out. In 2011, Nokia needed to layoff 18,000 people because its smartphone business was no longer competitive. To manage this layoff, it created a new process based on trust where, in exchange for staying until they were no longer needed, Nokia created a program to help employees find their next step.

“We tend to think that everyone trusts for the same reasons, but in actuality, deciding to trust is highly personal and based on our own specific interests.”

The program used company resources to give employees five different paths forward: find a new job at Nokia, find a new job outside Nokia, get a grant to start a new business, train for something new, or receive financial support to do something else entirely. The bet paid off. 60% of 18,000 employees across 13 countries knew their next step the day they left the firm. The quality of products was maintained and, in many factories, improved. The company achieved 33% of revenues from new products during the restructuring—the same percent of revenues from new products it normally obtained. This all sounds expensive, but the program cost less than 4% of restructuring charges.

Companies that build trust from the inside out can accomplish more than we ever thought possible.

4. Trust is in the eye of the beholder.

We tend to think that everyone trusts for the same reasons, but in actuality, deciding to trust is highly personal and based on our own specific interests. This makes gaining and retaining trust as an organization tricky because it requires dealing with different groups who have potentially conflicting interests.

For example, during the Great Recession, Honeywell CEO Dave Cote realized that his customers wanted the products Honeywell had promised them, his shareholders were concerned about stock returns, and his employees wanted to keep their jobs. He decided to prioritize meeting customer needs first because without them Honeywell wouldn’t have a future. He furloughed employees instead of laying them off. This cut costs, but also helped Honeywell retain a skilled workforce that could create the products customers wanted, instead of forcing Honeywell to hire and train new employees when the recovery occurred.

As a result of Cote’s balancing and prioritizing, when the crisis had passed and employees were taken off of furlough, Honeywell was able to outperform competitors’ stocks by over 20 points.

“Regaining trust is a long game.”

5. Lost trust can be regained.

All too frequently, we think that once trust is lost, it can never be regained. This is not true. Rather, broken trust can be rebuilt with a great deal of time and effort.

Regaining trust is a long game. Trust is regained by apologizing for the wrong that occurred, then taking accountability for the problem, and finally doing the hard work of fixing the system that created the problem in the first place.

Our favorite recovery story is about Recruit, a Japanese company that caused a scandal in the 1980s when the founder sold shares before a subsidiary went public in exchange for political favors. The resulting scandal was so great that the Japanese prime minister and his entire cabinet had to resign. Employees expected Recruit would die within six months, but managers made it a personal project to rebuild Recruit.

Managers authorized employees to personally apologize to customers for the harm the company caused—in fact, you can still read the story of the scandal and lessons learned on Recruit’s website. Managers invested in training, began a program to recognize employee innovation, and worked hard to make Recruit a good place. Working at Recruit became a mark of distinction on employee resumes. Today, Recruit is a flourishing global company with revenues north of $20 billion, with 65,000 employees worldwide.

Lost trust can, indeed, be recovered.

To listen to the audio version of the book bite read by Sandra J. Sucher and Shalene Gupta, download the Next Big Idea App today: