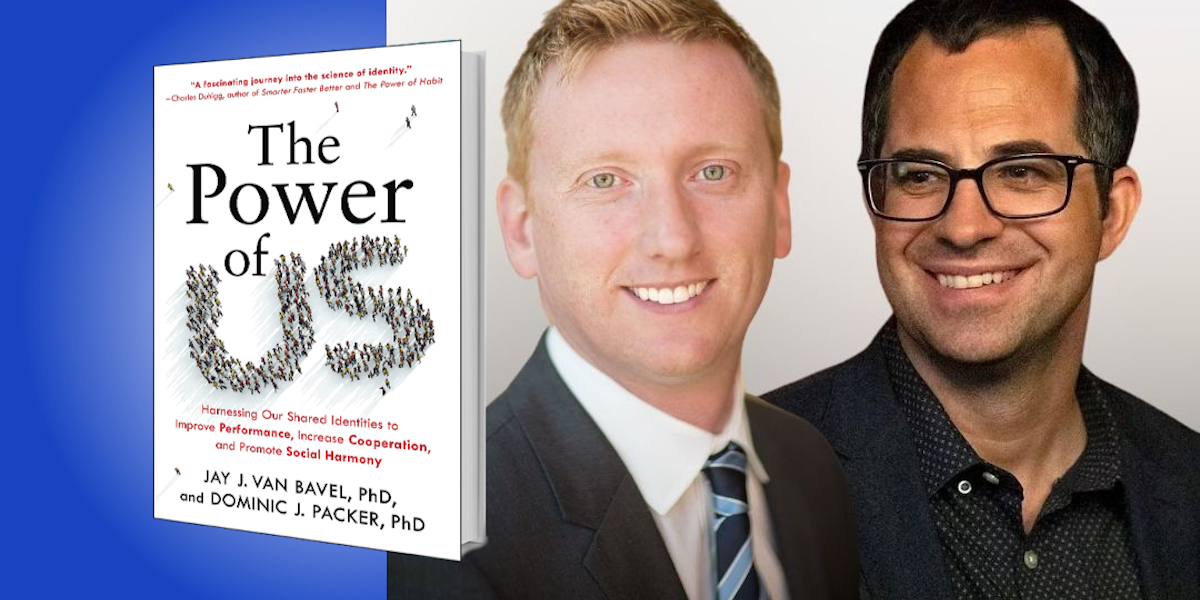

Jay Van Bavel is an Associate Professor of Psychology and Neural Science at New York University. From neurons to social networks, Jay’s research investigates the psychology and neuroscience of implicit bias, group identity, team performance, decision-making, and public health. Dominic Packer is a Professor of Psychology at Lehigh University. Dominic’s research investigates how people’s identities affect conformity and dissent, racism and ageism, solidarity, health, and leadership.

Below, Jay and Dominic share 5 key insights from their new book, The Power of Us: Harnessing Our Shared Identities to Improve Performance, Increase Cooperation, and Promote Social Harmony. Listen to the audio version—read by Jay and Dominic themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. We contain multitudes.

We are social psychologists who study how people’s identities affect how they perceive and understand the world, and how they make decisions. If we’re chatting with a stranger on a long flight, we might have them play a little game in which they complete the statement “I am ____” twenty times. Dom would say, “I am a professor, a father, a Canadian, a foodie, a bit shy, a fiction lover, etc.” while Jay would say, “I am a former hockey player, a New Yorker, a sports fan, a politics junkie, etc.”

Some of these things are individual in nature, characteristics that make us different from others. Some are relational selves, who we are in relation to specific other people, like being a parent or a child, a spouse or a friend. But a whole bunch are collective selves or social identities. Many of our most important identities are based in the groups we belong to, whether it’s our occupation, race, gender, nationality, political affiliation, or love of a sports team.

People often assume that they have a core self, a stable identity that they carry with them through the world. But as Walt Whitman famously said, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” Each of us contains many different identities that come in and out of focus at different times, often because of the social situations around us. Who I am at work is not the same as who I am with my kids, which is not the same as who I am as a fan of my local baseball team or the political identity I project online. As different identities are activated, it changes how someone perceives the world, as well as their preferences, their goals, and their decisions. Understanding that different parts of a person’s self operate at different times—and that many of those identities come from the groups they belong to—helps to make sense of a lot of human behavior that often looks irrational from an individualistic perspective.

“Each of us contains many different identities that come in and out of focus at different times.”

2. We have a readiness for solidarity.

Sylvia Rosalie Jacobson was a professor of social work at Florida State University. In September 1970, the flight she was on was hijacked taking off from Frankfurt. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine commandeered the plane, and flew Sylvia and her one hundred forty-eight fellow passengers to a remote airstrip in the middle of the Jordanian desert. There they sat for several days, and conditions on the plane slowly deteriorated. The cooling system broke down. The lavatories were overwhelmed. People fell ill. It was chaotic and scary.

As a social scientist, Jacobson observed events through the lens of her professional identity. And when it was all over and the passengers were rescued, she wrote a scientific article about it. She noted that despite the heat and the stress, there were moments of unity when the passengers gained a sense of shared identity. This tended to occur when their captors treated them as a whole. When the hijackers trooped through the cabin, the passengers were keenly aware of their common fate. In those moments, Jacobson wrote, “divisiveness was subdued. Despite differences of nationality, religion, race, sorrows, needs, values, resentments, and fears, there was unity.” The shared and traumatic experience that the passengers were going through provided a foundation to form a collective bond and sense of identity—and it helped them to organize and coordinate their behavior around common goals, including how to ration dwindling food and water supplies.

This is an important insight about human nature. When circumstances make us aware that we share a common experience or characteristic with others, a set of mental processes spontaneously kick into gear that cause us to feel like we are part of a group—that causes us to actually become a group. In dozens of studies, we have found that something as simple as assigning people to teams by tossing a coin produces immediate feelings of affiliation, changes in behavior, even changes in how people’s brains respond to ingroup and outgroup members.

“Crises create feelings of common identity; they generate solidarity that allows people to work together to address the problems at hand.”

One of the important implications of this idea has to do with how people respond during crisis. Leaders and policy makers often mistakenly assume that people will panic or behave selfishly during emergency situations. But research clearly shows that crises create feelings of common identity; they generate solidarity that allows people to work together to address the problems at hand. Great leaders know how to harness this psychology to overcome crises.

3. All reality is social reality.

In The Power of Us, we tell a story about the 1966 World Cup final between England and West Germany. Over 400 million people watched this incredibly tight match, and England won when they scored a goal 10 minutes into overtime… Except they didn’t! Later geometric analysis of video footage by computer scientists clearly shows that the ball didn’t cross the goal line. More than 50 years later, Germans are still bitter about that goal.

In the book, we told this story as an example of people seeing what they want to see, perceiving things in ways that confirm or benefit their identities. Once we’d written the book, it went through two rounds of legal review—one in the United States, and one in the UK. The US lawyers didn’t blink an eyelid at our story about the 1966 World Cup, but the UK lawyers were distinctly put out! They contested our claim that England had not scored the winning goal, and they advised that we instead say that the outcome was “controversial” or a “matter of contention.”

Funnily enough, these British lawyers were simply affirming our point. When identity is on the line, we are resistant to information that challenges beliefs about our groups. People naïvely assume they see the world for what it really is, but when you adopt an identity, it’s as if you put on a pair of glasses that filters your experience of the world. When things are ambiguous, identity tells you what is important, where to look, and when to listen.

Identities even influence what we taste and smell. In a pair of studies we ran in Switzerland, Swiss participants experienced the scent of chocolate more intensely than other scents—but only if they had been reminded that they were Swiss. The influence of identity on perception can also have significant negative outcomes, especially in contexts like policing and the justice system, where bias has terrible consequences for members of marginalized communities.

“When you adopt an identity, it’s as if you put on a pair of glasses that filters your experience of the world.”

4. Tribalism is a myth.

The idea that groups are inevitably discriminatory is incredibly common—but it’s also incorrect. Group identity does not always lead to prejudice and discrimination, dislike and disregard—indeed, the assumption that these outcomes are inevitable is one of the most prominent myths about identity.

The fact is that the norms we create and embody determine how we treat members of other groups. For this reason, groups are not simply “tribal,” as it is often said. When people use the term “tribalism,” they seem to be referring to a toxic pattern with at least three components:

- Intense conflict between ingroups and outgroups,

- Interest only in hearing information that confirms their own groups’ worldview, even if it is incorrect (a desire, as it were, to live in an echo chamber),

- Suppression of critical or dissenting voices from within the group itself (even punishing insiders with different views).

Though some groups have these characteristics, there is nothing inevitable about it! Rather than adopting discriminatory norms, groups can and often do embrace norms of tolerance, acceptance, and inclusion. For every white supremist organization, for example, there are dozens of humanitarian groups like the Red Cross or Doctors Without Borders working to improve the lives of people different from themselves.

Rather than placing a premium on information that confirms our worldviews, groups can adopt norms of accuracy, or what we call “evidence-based identities.” Scientists, lawyers, judges, investors, engineers, investigative journalists, and many others belong to groups with these sorts of identities. These groups are constantly interrogating reality, and people who fail to do so are often ostracized from the group! Groups can also create norms that embrace rather than suppress dissent and divergent perspectives. In each case, leaders play a particularly important role in creating, reinforcing, and perpetuating the norms of their groups.

“Leaders play a particularly important role in creating, reinforcing, and perpetuating the norms of their groups.”

5. Leaders manage identities.

A few years ago, we were at a conference in New York City, and we decided to go to a themed restaurant right off Times Square. I ordered a salad with grilled chicken, and when the food came, we were engrossed in conversation. Plus it was incredibly dim, so we weren’t paying close attention to what we were eating. But a few mouthfuls in, Jay noticed that there was something a bit strange and rubbery about the texture of his chicken. He took out his phone and used the flashlight to take a closer look—and the chicken was completely raw!

We called the floor manager over and showed him the chicken. He expressed mild concern, but said it was probably fine. When we asked what the restaurant was going to do about the situation, he said that they would knock half the price off the chicken salad—because Jay had already eaten half of it. As you can imagine, there might have been some shouting at this point. Jay ended up getting food poisoning that night, and he posted about the experience on Yelp. A while later he was contacted by the NYC Board of Health, who invited him to file a formal complaint.

There’s a lot going on in this story, but we’re telling it because it’s about a massive failure of leadership. What did the manager think he was doing? He probably thought that he was doing what his boss would have wanted, and maybe that he was acting in the interests of the restaurant: You don’t give food away for free, you don’t admit fault, you protect the bottom line. What a silly and narrow perspective on what represents the restaurant’s best interests—and what poor leadership to have employees interacting with customers while holding this understanding. After all, you shouldn’t have to tell your staff not to charge people for eating raw chicken—or not to serve it in the first place!

In The Power of Us, we argue that effective leaders manage social identities. They help their groups and organizations develop shared understandings of who they are and what they are striving for, and they unite their people around a sense of common purpose. These leaders create what social psychologists Alex Haslam and Steve Riecher call “engaged followership.” Rallying around collective goals, group members creatively and often independently figure things out and are able to act in the best interests of the group—and unleash the power of us.

To listen to the audio version read by Jay Van Bavel and Dominic Packer, download the Next Big Idea App today: