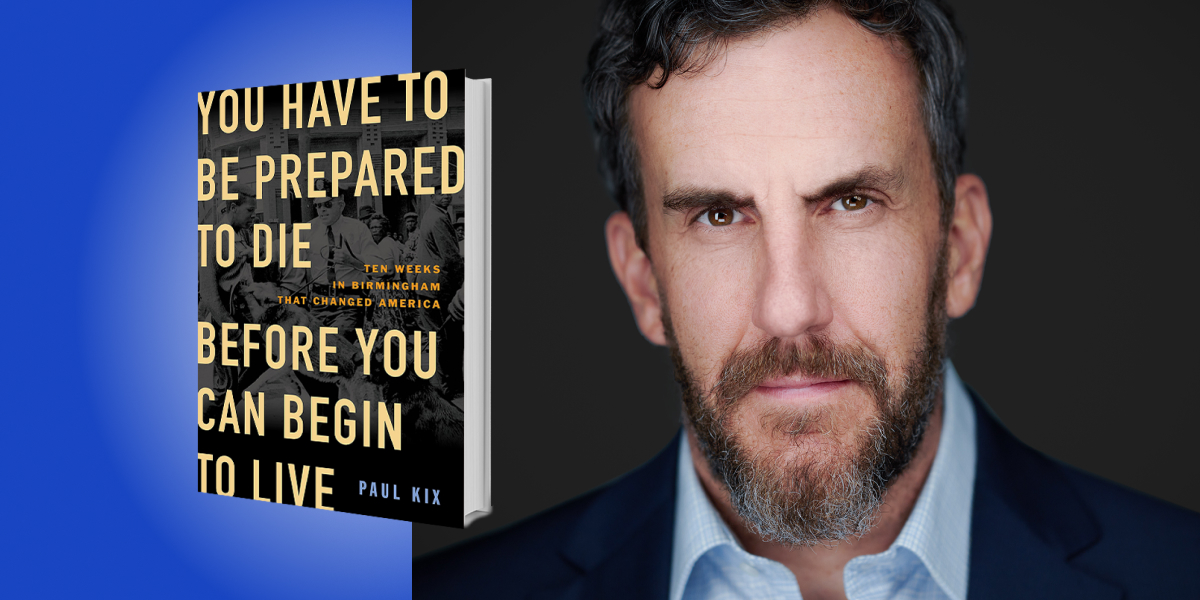

Paul Kix is an author whose last book was The Saboteur, a bestselling and critically acclaimed true story of the most daring man in World War II. His writing has also appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, GQ, and ESPN The Magazine, among other publications.

Below, Paul shares five key insights from his new book, You Have to be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live: Ten Weeks in Birmingham That Changed America. Listen to the audio version—read by Paul himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Lean into your vulnerability.

The Birmingham Campaign, in Birmingham, Alabama, was when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) descended on the city in the spring of 1963 to either break segregation once and for all or be broken by it. The Birmingham Campaign—or, as Martin Luther King Jr. and his deputies called it, Project Confrontation—altered the trajectory of the United States. Not just the Civil Rights Act of 1964, not just the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but King’s martyrdom in 1968 and then a new life for his country, right down to me marrying a Black woman in a former Jim Crow state and raising our three Black kids on a shaded street where no one harasses us for who we are. Sixty years after Project Confrontation, I owe my life and livelihood to that campaign’s success.

So, let’s start with where the SCLC was back then. They were broke. They were ridiculed by other civil rights groups as pompous and weak. They had just staged a year-long campaign in Albany, Georgia, and lost, which the press—Southern and Northern—called the most humiliating defeat of King’s career. By the early months of 1963, King’s SCLC had not won a single civil rights campaign since its founding, seven years prior.

Against that backdrop, Wyatt Walker, the executive director of the SCLC, said, “All our flaws can be turned into strengths if we look for the lessons in each.” Walker spent months analyzing the SCLC’s vulnerabilities and weaknesses and found that the organization wasn’t vulnerable or weak. The SCLC had just made a couple of bad assumptions in the past. The first was that it had always staged campaigns in conjunction with other civil rights groups. The second was that these campaigns had been waged in places where the groups thought they might win.

In the months prior to Project Confrontation’s debut, Walker wrote a blueprint for how it should proceed. First, the SCLC should be the only group overseeing this campaign. Second, they should stage it not where they might win, but where they were sure to suffer. If they and their volunteers suffered violence, it would get to the conscience of white America and the Kennedy brothers who governed it, in ways that no campaign had.

“Sixty years after Project Confrontation, I owe my life and livelihood to that campaign’s success.”

That’s how the SCLC settled on the most violent, most racist city for Project Confrontation: Birmingham, Alabama. Walker’s insights astounded everyone within the SCLC. The only reason he developed these insights was because he had the temerity to look where others hadn’t—deep into the SCLC’s own humiliations and vulnerabilities. To paraphrase what Walker would later say himself: Look into your own vulnerabilities and you will find a reservoir of untapped strength.

2. Courage is not mandatory in life.

Birmingham, in those days, wasn’t so much a city as a site of domestic terror. The Klan castrated Black men. The cops raped Black women. The city’s public safety commissioner, Bull Connor, gleefully and often publicly referred to Birmingham as Bombimgham, for all the Black businesses and residences that were dynamited. CBS’s Edward R Murrow reported from Birmingham prior to King’s arrival and told his producer he hadn’t seen anything like this place since Nazi Germany.

All of this is why King thought he and/or his deputies would die for going down there. So how did they do it? What sort of pep talks did they give themselves? What sort of courage did they display? Well, the real courage they showed was admitting that they weren’t courageous at all. King delivered a mock eulogy before the SCLC left for Birmingham. It was a way to acknowledge the obvious—they were all terrified of campaigning down there—and it was also a way to ease the tension that lived within that fear. It worked. Showing each other that they all had fear was a way to buoy themselves so that they could withstand it.

Then they found something greater than it when they found that the best elixir for fear is action, as King later wrote. For King and the leaders of the SCLC, that meant arriving in Birmingham and just starting the campaign. Putting in the effort, day after day, before they were ready, before they were courageous. It was never not terrifying, but because the SCLC was in the midst of responding to it, the terror wasn’t overwhelming either. Action decreases fear. This is true in all of life’s encounters.

3. Your grand plan is never the final plan.

It didn’t matter that Wyatt Walker had promises from over 300 volunteers and an association of Black Baptist ministers. Hardly any of those volunteers stepped forward once the SCLC arrived in Birmingham. The reasons were numerous, but the upshot was this: The SCLC started the largest campaign of its life with the fewest number of volunteers it had ever assembled. Meaning, they had to adapt—fast.

“The best plan is the one where you are constantly adapting to the circumstances around you, looking for the best solution.”

That’s when the SCLC’s James Bevel (its operations lead and a man far younger than the middle-aged King and one who favored overalls instead of the standard Movement-issued conservative suit) told King the campaign would only work if children led it. Their parents, you see, might get fired for protesting. But kids didn’t hold jobs and only want a future better than their decrepit present, where they got discarded sporting equipment and school textbooks that were a generation out of date. King did not want to use children against the brutality of Bull Connors cops and the Klan. But the campaign turned anemic with only adults and, meanwhile, Bevel was training kids by the dozens, hundreds, and then thousands in the means of nonviolent protest.

Bevel realized something key to the problem of the Birmingham campaign, which is also any problem in life. The best plan is the one where you are constantly adapting to the circumstances around you, looking for the best solution.

4. Suffering is eternal. Victimhood is optional.

In early May 1963, Bevel led a campaign within the Birmingham Campaign which he called, D-Day. It was thousands of children skipping school on May 2nd and 3rd and descending on Kelly Ingram Park, across from the 16th Street Baptist Church. The objective was to get to the white-owned and white-run downtown and stage massive protests for civil rights there.

But on May 2nd and 3rd, Bull Connor and the Birmingham Police Department stood with guns and German Shepherds and fire-hoses that could tear mortar from bricks or dislodge bark from trees at a distance of 100 feet. Bevel had children march right into those guns and dogs and firehoses anyway. The result was savage, apocalyptic, the worst thing war photographers present that day had ever seen. Children were mauled by dogs, as if the dogs were feasting on them. Children backflipped in the air from the firehoses, their clothes just disintegrating on their bodies, their hair scalped as the firehoses hissed across their skulls. The children knew this might happen. Bevel had prepared them for it. And because they had known they would likely suffer, they did not turn their suffering into victimhood. They did not stop marching. By the dozens and then hundreds and ultimately thousands the children continued to march in early May.

“When you know that everyone in life will suffer, you realize that your own suffering can serve a cause.”

As a result, they could not be stopped and Birmingham began to desegregate. When you know that everyone in life will suffer, you realize that your own suffering can serve a cause: At minimum, it forges you into a better person. At most, it changes the world.

5. Control what you can and then watch your sphere of influence grow.

The attacks grew more vicious. The hotel where the SCLC stayed was bombed. The home of King’s brother A.D. was bombed. But by mid-May 1963, the SCLC saw these attacks for what they were, desperate attempts by racist whites to remain in control. But white authority could no longer control anything so long as the SCLC realized what was within its control, which was the ability to stay calm in the face of such attacks. The ability to go to the press and say that the volunteers and SCLC itself would remain peaceful regardless of what happened to them, which began to engender the support of the nation to the cause of the SCLC.

King’s group and its volunteers controlled what was within their purview, their words and actions. By never stooping to white authority tactics and showing the press over and over the brutality of how whites treated Blacks in Birmingham, the Kennedy administration pressured white civic leaders to sign a document desegregating Birmingham, the most racist city in America.

As a result of that desegregation pact, other American cities began to stage their own protests. Suddenly there were fifty Birminghams, a hundred Birminghams, all over the nation, and the Kennedy brothers realized the only way to find solutions for them all was to do the one thing they had been loathe to do: Author civil rights legislation. For them, this could mean the end of Kennedy’s re-election bids, according to Kennedy’s own pollsters. But Bobby Kennedy became convinced that real and lasting civil rights legislation was what was needed now.

So, on June 11th, King got his wish. Jack Kennedy went on national television and said the time had come for the white man to see the Black man as his equal. That day, set in motion the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The spring of 1963 altered America in ways that no season had before and no season has since. This history teaches lessons on how to live with courage, dignity, and righteousness, and, perhaps most importantly, teaches the power of the ability to control what is within your control. Do that well. Do that for a while. Then watch your sphere of influence grow.

To listen to the audio version read by author Paul Kix, download the Next Big Idea App today: