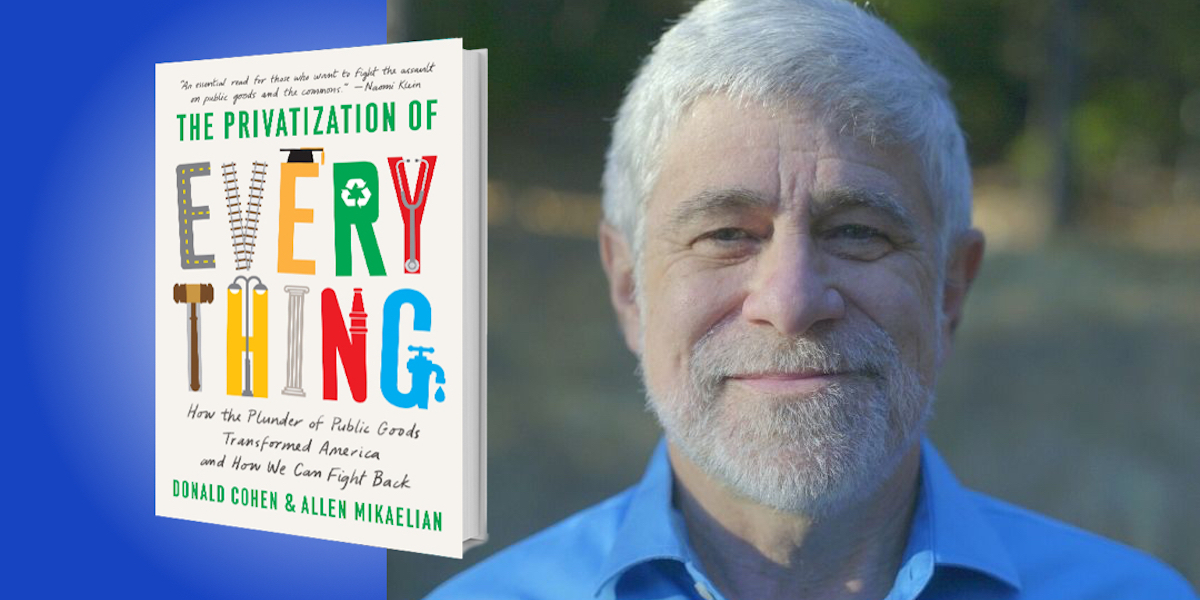

Donald Cohen has been running a national research and policy institute, In the Public Interest, on issues of privatization for over 10 years. He has seen first-hand how governments provide essential services—schools, water, libraries, parks—and how they use or misuse contracting as a way to provide those services. His opinions have appeared in the New York Times, Reuters, and the Los Angeles Times, to name a few. Co-author Allen Mikaelian is a New York Times bestselling author and doctoral fellow in history at American University.

Below, Donald shares 5 key insights from their new book, The Privatization of Everything: How the Plunder of Public Goods Transformed America and How We Can Fight Back. Listen to the audio version—read by Donald himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Public things are for all of us.

There are things we all need to survive and thrive: big things like public health, mobility, knowledge, democracy, education, shelter, clean air and water, and the ability to communicate with each other. In a democracy, we—the public—should be able to decide what are essential public goods, available equally to all.

But economics textbooks define “public goods” as only things that we can’t be prevented from using, and that one person’s use of doesn’t stop others from using them, too. Things like street lights—because you can’t stop someone from using the light, and if you use the light to read a map, everyone else can use it at the same time to read their maps. This definition means that the market—not the public—decides what’s public and what’s private. The market, thus, controls many of life’s “essentials.”

Take health care: it fits the definition of a private good. You can exclude people from getting it, and there are only so many hospital beds, doctors, and nurses. If we accept that it’s a private good, then we are saying that those with resources should be able to meet their health needs, while those with fewer resources shouldn’t. Yet as a nation, we can decide that everyone should have the same health care, regardless of income or status.

“As a nation, we can decide that everyone should have the same health care, regardless of income or status.”

Likewise, we can decide that everyone should be able to go to college. Or that every family should be able to put their children in high-quality childcare. Or even that every citizen should have an equal voice in our democracy.

That doesn’t mean that we get every aspect of public goods directly from government agencies. Sometimes we do, like Social Security, the neighborhood library, or a county hospital. Sometimes it means setting standards and hiring inspectors for consumer goods, like food, to ensure it’s safe.

In a democracy, we can decide what those essentials are that should be available to everyone.

2. Privatization weakens democracy.

Private interests and public interests are simply different. Not good, not bad, just different. Private companies sell things, while the public wants to ensure that people have the things they need. The problem comes in the fine print of public-private contracts and agreements, which, by design, embed private control over our public goods.

For example, 12 years ago, Chicago (like all cities) was hit hard by the recession and swimming in red ink. Out of desperation, they took an offer from global investors and a national parking company to give the city $1.1 billion—up front—in exchange for control of the city’s 36,000 parking meters for 75 years.

Everyone thinks it was a terrible and shortsighted deal, but the worst part is that it was an assault on democracy. Chicago city transit planners are unable to implement planned transit alternatives, like BRT or bike lanes, because the contract requires that the city buy the parking spots back to cover revenue that could have been generated over the life of the contract.

“That’s a straitjacket on democracy.”

It makes sense for the contractor, but it doesn’t make sense for us. It forces elected officials to consider the impact that new policies could have on company revenues, rather than freely create policies that respond to a changing world. That includes basic city responsibilities such as land use, housing, climate, transportation, and parks.

In other words, the contract takes away the power that democratically elected city leaders need to do the job they were elected to do. That’s a straitjacket on democracy, and unfortunately, those constraints are a common feature of public-privatized contracts.

3. The market is the wrong tool to deliver public goods.

Some argue that market-style competition will provide more and better public services. Certainly, competition can generate new products and new ideas, but it can also have a downside when it comes to public goods.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the Trump administration’s response was to hand it to the market. States were competing against one another for protective equipment and COVID tests. That drove prices up and left states scrambling. Jared Kushner said outright, “Free markets will solve this. That is not the role of government.” That approach failed miserably, so Operation Warp Speed was launched to bring government coordination to pandemic management.

Another example is charter schools. Charter schools were originally intended to be laboratories of innovation that test ideas before sharing the good ones for the benefit of all students. Unfortunately, it’s become something different.

“Jared Kushner said outright, ‘Free markets will solve this. That is not the role of government.’ That approach failed miserably.”

Charter schools compete with neighborhood schools for enrollment (and the education dollars that come with each student). The basic idea is that parents will choose the good schools, and the poor schools will either improve or fail. That hurts families, divides communities, and leaves poor schools with fewer resources to make necessary improvements. It also creates incentives to manipulate the market.

Charter schools are legally required to accept all students, but some charters use a variety of schemes to keep out new students or move out existing “problem” students—like special education students, or ones with behavioral issues. These students might bring down the schools’ test scores and lead to fewer enrollments. In 2015, the New York Times found that a charter school principal kept a “Got to Go” list of students, and that other schools were pushing kids out as well.

Finally, competition also leads to secrecy, not sharing the things we could all benefit from. Charter school employee handbooks often include non-disclosure agreements that threaten legal action if teachers reveal “trade secrets.” That includes lesson plans and curricula, precisely the stuff that should be shared broadly—and that, by the way, was paid for by the public.

4. A privatized America is a divided America.

Political, cultural, and religious divisions in America are nothing new, but the pandemic unveiled a profound problem: we no longer see our individual fates as tied together. Privatization is making it worse by further dividing us.

“After 800,000 COVID deaths, it’s clear that the health of all of us depends on the health of each of us.”

The privatization of public education began as a reaction to Brown v. Board of Education. Parents didn’t want their children in the same schools as Black children. The policy solution they turned to was school vouchers, which turned families into consumers who could choose private, segregated schools. It was described as “parent choice,” but it was really just racism.

Today, we’re seeing that same transformation throughout the economy. We’re increasingly individual consumers of basic public goods, rather than citizens who look out for one another and do our part for society. In 1975, states funded 58 percent of the total cost of higher education. Today, it’s 37 percent, with higher tuitions filling the gap. With public funding, colleges could keep tuitions down and make school accessible to more students. Without state funding, students bear mountains of debt, or they just don’t go at all.

At the other end of our education system, Pre-K childcare is a fully privatized market good. It’s a commodity purchased by parents, when it should be a public good. The Treasury Department found that more than 60 percent of families are paying more than they can afford.

We are increasingly on our own in the marketplace to meet our basic needs. Sherrilyn Ifill, the president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund said it best: “We are being destroyed by the idea that we are not interdependent.” Indeed, we are tied together whether we admit it or not. After 800,000 COVID deaths, it’s clear that the health of all of us depends on the health of each of us. The same could be said about educating all children, not just the ones in your family, or about making sure that everyone has clean water.

“Turn on the faucet—that’s a public service. The paint on your wall used to contain lead until the government took action. The weather apps on our phones use data collected by the National Weather Service.”

5. Public services are both ubiquitous and invisible.

There are many public resources that we are hardly aware of, despite coming across them every day. And despite all our challenges, there’s plenty to be impressed by and even proud of.

Turn on the faucet—that’s a public service. The paint on your wall used to contain lead until the government took action. The weather apps on our phones use data collected by the National Weather Service.

The problem is that when we are unaware of the government services that help us get through life, we more easily embrace anti-government, anti-public attitudes.

If we want to ensure democratic control over the essentials we all need (whether they are done by public workers or a private company), then first, we need to “surface the state.” This means becoming aware of the public things that surround us. Next, we need to be clear about the public purpose of each of these things, and how they are essential for all of us. The roads are about mobility, our schools are about an educated country, and health care is about a healthy nation. The third step is acknowledging that there’s no free lunch; we have to pay for the things we need. That means raising and spending money from all of us, for all of us. That’s democracy.

Finally, there’s room and need for public and private institutions. When it’s about the essentials we all need to survive and thrive, then the public has to be in charge, even when private companies do the work. That’s also democracy.

Democracy means that we decide the important stuff: what are essential public goods.

To listen to the audio version read by co-author Donald Cohen, download the Next Big Idea App today: