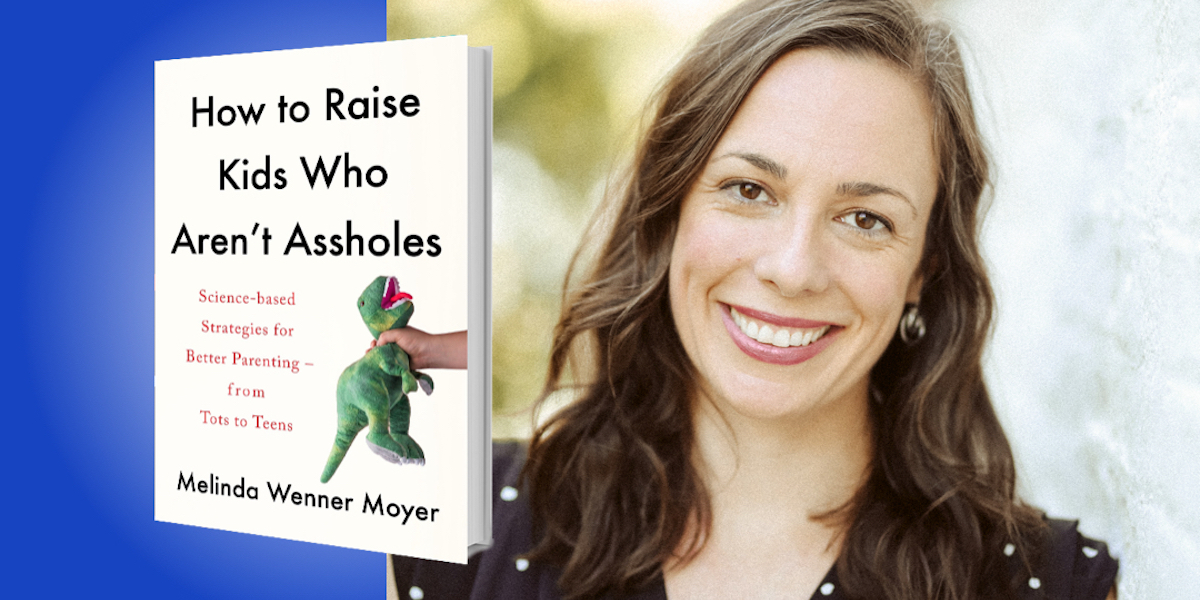

Melinda Wenner Moyer is a science and parenting journalist, a contributing editor at Scientific American magazine, and a regular contributor to the New York Times, Washington Post, and other national magazines and newspapers. She is also a faculty member in the Science, Health & Environmental Reporting program at NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute.

Below, Melinda shares 5 key insights from her new book, How to Raise Kids Who Aren’t Assholes: Science-Based Strategies for Better Parenting—from Tots to Teens (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Melinda herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Talking about feelings makes kids more generous.

Research shows that parents who talk about feelings are more likely to have generous kids. In a 2013 study, researchers invited toddlers and their mothers into a lab and asked the moms to read a book to their kids. As they read, the researchers recorded how frequently the moms labeled and explained the characters’ feelings and encouraged their kids to do the same. They assumed that moms who talked about feelings in the study talked about feelings a lot at home, too.

Then the toddlers were invited, one by one, to play with a researcher in another room. While they played, the children were given opportunities to be generous—to share toys and to help the researcher when they pretended to need something. The researcher complained, for instance, that she felt cold, when a blanket was just out of reach—to see if the child would go get the blanket and give it to her. The researchers found that the children of moms who frequently engaged with their kids about feelings were much more likely to help and share. In other words, talking about feelings helps kids develop the skills they need to be compassionate and generous.

2. To build resiliency, let kids fail.

One of our most important jobs as parents is to protect our kids and keep them safe. But when this instinct is too well-honed, it can be counterproductive. When we start protecting our kids not just from serious harm but also from challenge and failure, we hold them back—and can even make them feel worse about themselves.

“When we start protecting our kids not just from serious harm but also from challenge and failure, we hold them back—and can even make them feel worse about themselves.”

Studies suggest that kids can struggle with feelings of low self-efficacy when their parents do too much for them. Researchers at the University of Illinois surveyed more than two hundred students from second through fifth grade, asking them how they felt when their parents helped them and made decisions for them. The older the kids were, the more they considered their parents’ help to be a sign that their parents considered them incompetent. When we instead give kids the opportunity to navigate challenges themselves, we show them that we have faith in them. We also communicate that it’s OK to mess up, because every mistake is an opportunity for learning and growth.

Another way to build resilience in kids is to emphasize effort more than skill or ability. This invokes what Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck calls a “growth mindset.” When we tell kids they’re smart, or they’re naturally good at math, they start to think of ability as a fixed trait, which they either have or they don’t—effort doesn’t matter. When they start thinking this way, they then start to consider challenges and failures as signs of ineptitude. If, instead, we emphasize to kids that smarts and ability are learned through effort and practice, they start to see challenges as opportunities for growth and learning.

3. Respond to misbehavior with empathy, then guidance.

Often, when kids act out, parents assume they’re doing it on purpose—they’re defying us, they’re trying to make us mad. But in reality, kids often misbehave because they’re lacking the skills they need to handle the situation rationally and gracefully. And when we get mad at kids for acting out, we upset them more, which makes it harder for them to listen to and learn from us.

Research suggests that the best way to respond to misbehavior is to first validate your child’s feelings. If your daughter has thrown a book across the room in rage, you might say “Oh wow, you look so angry,” before moving on to the issue of the thrown book. Give her the opportunity to talk about her feelings by asking her what happened, and then reflect those feelings back to her. “Oh, I totally get it—you’re mad because you weren’t invited to Leah’s birthday party.” Acknowledging your child’s feelings will help her understand them and learn to manage them better. Research has shown that when parents shame kids for having big feelings, those kids are more likely to have problems regulating their emotions in the future.

“When we get mad at kids for acting out, we upset them more, which makes it harder for them to listen to and learn from us.”

Then, once your child has calmed down a bit, think about what guidance you want to impart—what lesson you want to teach in that moment. Perhaps you want to convey to your kid that although it’s OK that she’s mad, it’s not OK for her to throw things, because someone could get hurt. You might also talk about what she could do next time she’s angry that would be more appropriate. When we respond to bad behavior with empathy and guidance, we help our kids learn from the experience and manage the next difficult situation more appropriately and constructively.

4. To prevent racism, talk to children about race.

White parents sometimes say things like “my kids don’t see color,” or “my kids are colorblind.” But research shows that children notice differences in skin color from the time they are babies. And kids are like little detectives: They are constantly looking around, trying to understand how the world works and which social categories matter and why. They’ll notice that hair color doesn’t matter when it comes to how much power people have and where people live and who people are friends with, but that race does matter. They see that all but one U.S. president has been white, that heroes portrayed in most movies are white, and then they start to make inferences. If parents and teachers don’t talk to children about the role that racism plays in shaping the racial hierarchy that exists in our society, kids may conclude that white people have more power and prestige because they’re somehow smarter or better.

Research confirms that talking about race and racism reduces the likelihood that white kids will develop racial prejudice. (Families of color usually talk about race a lot, in part because they have to. It’s really only white families who go out of their way to avoid the topic.) In one study, researchers presented short biographies of famous white and Black people to white elementary-aged children over the course of six days. Half of the kids heard biographies that discussed the discrimination experienced by the Black individuals, while the other half heard biographies without any details about discrimination. Afterwards, the researchers gave the kids tests designed to assess their levels of racial prejudice. Compared with the kids who weren’t taught about discrimination, the kids who were taught about discrimination had more positive attitudes towards Black people.

“It’s far better to talk about race with your kids and make mistakes than to avoid the topic entirely.”

One thing I want to acknowledge is that it can feel really awkward to talk about race if you’re white. That’s in part because many white people have been raised to consider race a taboo subject. So it may be hard at first, but it gets easier the more you do it. And it’s OK if you make mistakes, or you don’t know how to answer all your kids’ questions. You can always revisit them later, when you’ve had some time to think. Still, it’s far better to talk about race with your kids and make mistakes than to avoid the topic entirely.

5. When kids fight, be a mediator, not a referee.

When children get into arguments, our tendency is to either let them work out the conflict for themselves, or to jump in and referee—to say “OK, Jimmy, give the teddy bear to your sister.” But research suggests that these strategies backfire. When we leave kids to work out conflict by themselves, they rarely work it out cooperatively—the older or more dominant child typically wins, which can teach kids that coercion and bullying are good ways to solve problems. And when we referee, the losing child feels resentment toward the winning one (and toward you), which fuels further conflict.

But there’s another way—a way to use conflict to teach kids about empathy and cooperation. It’s called mediation. First, intervene in the fight. Acknowledge that the kids sound upset, and put anything they’re fighting over away for a few minutes. Next, ask each child to describe what happened and how they feel, and identify points of contention and common ground. Then help the kids brainstorm solutions to the problem that feel fair to everyone.

Mediation works because it acknowledges and validates kids’ emotions, and it helps kids understand the other child’s perspective. This not only makes each child feel heard and respected, but it teaches each child to understand and respect other people’s feelings, too. Research from clinical trials has shown that mediation works; one 2014 study found that after parents were taught to use mediation techniques with their kids, their children were better able to discuss their and their siblings’ feelings, identify potential solutions, and arrive at compromises on their own.

To listen to the audio version read by Melinda Wenner Moyer, download the Next Big Idea App today: