Carl Safina is an ecologist and a MacArthur Fellow “genius” award-winner. He holds the Endowed Chair for Nature and Humanity at the State University of New York at Stony Brook and is founder of the not-for-profit Safina Center. His writing appears in the New York Times, TIME, The Guardian, Audubon, National Geographic, Huffington Post, CNN, and elsewhere.

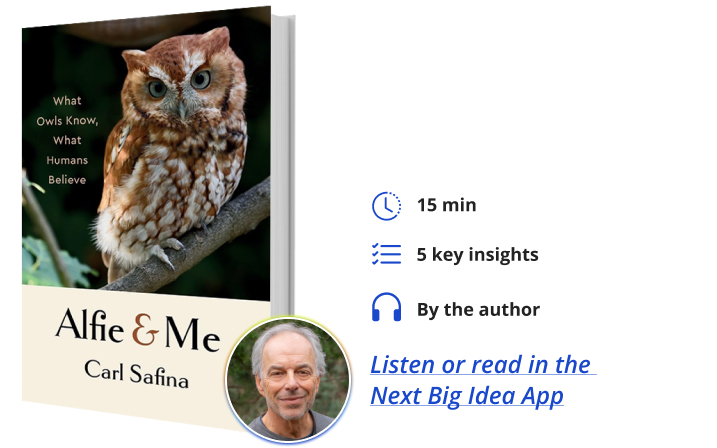

Below, Carl shares five key insights from his new book, Alfie and Me: What Owls Know, What Humans Believe. Listen to the audio version—read by Carl himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. A rescued wild creature can become our portal into the wild world all around us.

The COVID-19 shutdowns that forced us to spend our year at home coincided with the presence of a free-living screech owl, rescued near death, who we raised and then allowed to wander off at her own pace. “Alfie” surprised us by deciding to stay around our backyard, getting herself a wild mate, and becoming a mother of three youngsters.

The little owl in this story is a living being in all the ordinary and extraordinary ways. She is not a messenger—as some people believe owls are—but she is in no sense “just an owl.”

Our deeply shared history as living beings is why Alfie and I had the capacity to recognize each other and be brought into a relationship by that strange binding called trust. Trust was the bridge across which she and I, and my wife Patricia, shuttled.

Early in Alfie and our relationship, I realized something mutual was happening. Alfie was becoming a portal to a parallel reality adjacent to our human existence. She brought us closer to the living world, softening borders between light and darkness, deepening perception beyond the usual.

Alfie was my passport to that older, saner realm, usually denied to foreign visitors. She was my little friend.

2. Wild animals are individuals.

Humans, of course, have differing personalities and temperaments, and people who know dogs or cats—to the extent cats let themselves be known—take personality differences for granted.

Yet we assume that all individual wild creatures are the same—mainly because we don’t know any actual wild creatures. But wherever researchers have looked for individuality in other creatures, they have found it.

“Courtship in these birds isn’t just a phase but, similarly to humans, is an unfolding process.”

Alfie had her own particular personality. Her first mate was rather relaxed around us; her second mate always tried to drive us away from their young ones. You might think that having been raised by humans, Alfie wouldn’t know she was an owl. While she continued to recognize and respond to Patricia and me with complete confidence and even physical affection, she responded completely normally to her wild mate. She took superb care of her eggs and her young ones.

Watching the owls for several hours a day showed me that courtship in these birds isn’t just a phase but, similarly to humans, is an unfolding process. Alfie and her mate were at first very tentative, but as they built trust, the bond strengthened, and they spent more time together. Physical mating also progressed, awkward initially and then increasingly skilled—and avid.

3. We tend not to know or see them. But they are our neighbors.

The 2020 Covid pandemic was fortuitously timed to allow me to observe Alfie’s first free-living year closely. Many people found a silver lining to that awful year in pets and gardens. Friends said the birds were singing louder. But that wasn’t it. The humans were quieter. News media showed mountain goats on Welsh sidewalks, jackals in Tel Aviv, and daytime raccoons sauntering through Central Park in New York City. Deer wandered in a seemingly de-peopled east London. The BBC showed us flamingos on a de-touristed Albanian lagoon and pumas in Santiago, Chile.

From Alfie’s portal, I’d reenter the human realm and confront the headlines. Covid. Unhinged politics. Racial frictions. Cultural factions. Lying denials, lying assertions. Troops clashing in disputed areas. For me, the daily rhythms and quiet sanity of the owls’ world contrasted with humankind’s self-inflicted torments.

4. Our culture’s view of the wild is not typical among human cultures.

Alfie is flesh and feathers; her heart pumps blood red as ours. She has her comforts and fears. These are everyday things, sure, but everyday things are the result of our planet’s entire three-and-a-half-billion-year history.

“Everything is here now” is a tenet of Zen Buddhism. This moment required all of time. The whole journey is present. In our mother’s womb, our temporary gills, fins, and tail manifested the genetic memory of life’s family portrait. As adults, we retain and procreate our fish-originated spinal column, ribs, and organs, and the gill-originated jaw with which we voice human thoughts. The deep ancestors’ essence is everywhere. We are one point in the unfolding. We are not just a speck in time and the universe; we are the universe and all of time in a speck.

Alfie is a very real little being, yet I suppose she is, in this way, a bit of a messenger. After all, Alfie has managed to convene us, you and me, here in this moment. For most of human history, Indigenous peoples everywhere perceived Life and the cosmos as relational. Similarly, ancient Asian traditions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Taoism, Confucianism, and others elevated the human role in maintaining relational harmony among worldly forces. All saw in nature’s diversity a unity with things deeper, bigger, and eternal. (Physicists have indeed found that deeper things create the world we see.)

Then, in ancient Greece, a different thought arose. Plato posited an ideal realm outside of space and time and disparaged our flawed material world. Judaism absorbed his dualist split between ideal and real, and Christianity amplified it. Later, René Descartes’ faith—and his fear of Catholic Inquisitors—helped ensure that the West’s philosophical underpinnings carried into the scientific and industrial revolutions this deprecation of the world.

In almost all other belief systems, the world contains the most holy and important things; in the Western dualist perspective, the world is often the least holy, least important thing. The Western view has globalized as a worldwide monetary economy whose valuations reflect this devaluation.

“Dissociation is dualism’s contagious ailment, civilization’s self-generated epidemic.”

Physics, chemistry, astronomy, geology, biology, and ecology all affirm that existence is relational at all scales of space, life, and time. But we have created instead a transactional economic system that allows all parties to dissociate from their interactions—and the consequences.

Nothing is horrific enough to unify us once we are sufficiently disengaged from the world and one another. Not mass shootings, not intensifying storms and rising floods, certainly not oceans of plastic, nor plummeting populations of birds and bugs. Dissociation is dualism’s contagious ailment, civilization’s self-generated epidemic. It all works overtime to turn the planet’s once splendid living family into a broken home.

Our systems depend on the destruction of natural systems. Our way of living, writes Zen master Susan Murphy, “does evil by countless repetitive, cumulative failures of care and conscience.” Even those of us who are aghast help grease those gears.

And here we are, simultaneously facing the extinction crisis, the toxics crisis, the climate crisis, while a world of eight billion humans, having literally set the natural world on fire, stares. It is easier to imagine the end of the world than how we will end our destructive habits.

5. There is a lot to learn from wild lives and from other traditional cultures.

Life on this planet is vulnerable. Yet, it’s also capable of resilience. The spectacular recoveries of creatures like bald eagles and humpback whales do not fill me with confidence—their rescue from our pesticides and violence entailed protracted battles, but they inspire me with hope. Saving them required merely a new willingness to value and accommodate other-than-human life. That’s important because a few more accommodations are needed.

Alfie has been a connector for me, not only between her world and mine—a single world that we share—but between my familiar ways and my expanding perspective. Alfie opened the portal, allowing me to participate in aspects of life rarely available in a human-centered existence. Things small and lovely, often delightful, have altered my view of her life and my own.

The little things are the big things. In our accustomed lives, we think and act transactionally, but Alfie showed me that what’s paramount is to live in a relationship. People for many thousands of years lived in relationship with nature and with their communities. If there is a major message to take from traditional and Indigenous cultures, it is that to live in relation with the living world and the people around us is the direction we need to go; it’s how we might heal.

When we take the focus off ourselves, we become better, and so do the lives around us.

To be fully present in life and love, so natural for Alfie, remains a work in progress for me. Alfie is the perfect little Zen master. She lives a freedom untainted by critique or doubt, a liberty buoyant and accessible to her as the air beneath her wings. She is pure presence, here now. Alfie showed me what’s possible when we blur our accustomed boundaries. That realization can inspire a life’s work. Or be as simple as a little owl outside the back door.

To listen to the audio version read by author Carl Safina, download the Next Big Idea App today: