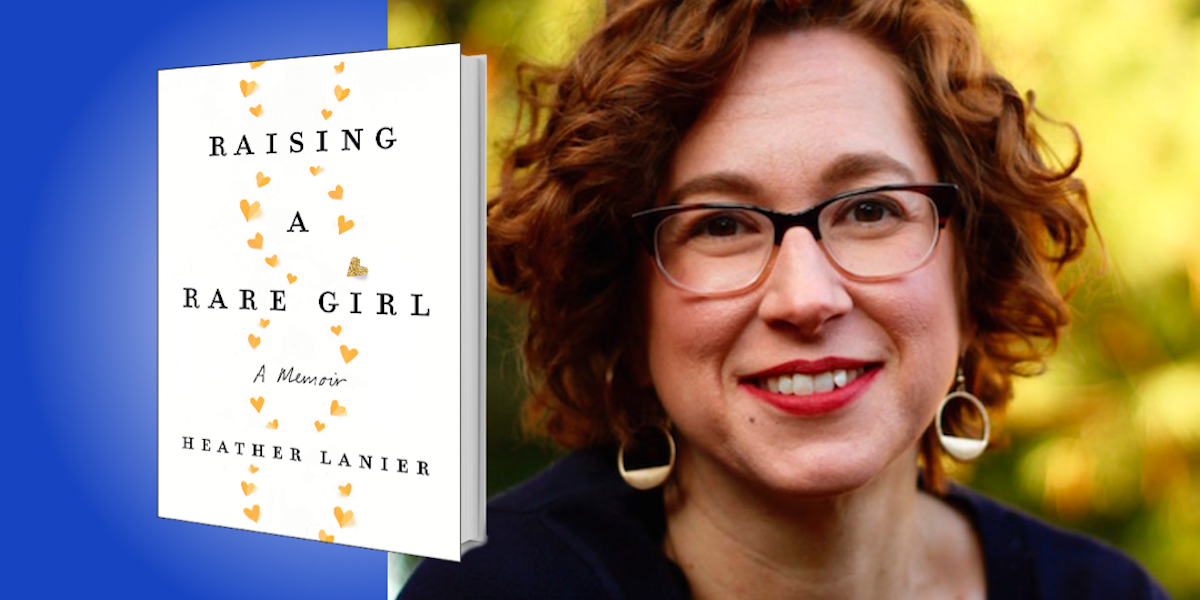

Heather Lanier is an essayist, memoirist, and poet whose nonfiction has appeared in The Atlantic, Salon, Fourth Genre, Brevity, and elsewhere. A recipient of an Ohio Arts Council Individual Excellence Award and a Vermont Creation Grant, she’s an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Rowan University. Her TED talk, “‘Good’ and ‘Bad’ Are Incomplete Stories We Tell Ourselves,” has been viewed over two million times.

Below, Heather shares 5 key insights from her new book, Raising a Rare Girl: A Memoir. Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. The point of life is not to be superhuman—it’s to be ultra-human.

When my daughter Fiona was diagnosed with a rare chromosomal syndrome, I felt groundless—but I realized a great human truth. There is no way to guard ourselves against difficulty and fragility. We can’t use our minds or our supplements or our religions to coax our way out of the human condition. So our work is not to become perfect or superhuman—it’s to become ultra-human, as human as humanly possible. This means being vulnerable, sometimes aching and sometimes struggling, but always being open and real and present to the whole messy road.

2. “Normal” is a king we do not have to worship.

When we ask ourselves, “Is this normal?” we often mean, “Is this okay?” We revere normalcy, which is thanks to the bell curve. It was a Belgian statistician, Adolphe Quetelet, who first applied the bell curve to moralize human measurements. He created and hailed the average man. But once we turned the bell curve into a moral measurement, believing that outliers were bad, deviant, or broken, we distorted the truth of our humanity, which is that our diversity is beautiful. And disability is an expression of that diversity.

3. The way professionals frame a person profoundly impacts their perceptions.

After my daughter was born, a pediatrician came to examine her. He was concerned about her tiny size, and he said, “It’s either bad seed or bad soil.” He was likening my new baby to a bad plant. But when my husband and I met with a geneticist, he smiled and greeted my daughter with delight. Then he used words like genetic “deletion” instead of “defect.” This isn’t just an issue of semantics—it’s about how language reflects a way of seeing, and transfers that way of seeing to others. Through his language and framing, that geneticist took my daughter’s life back from a culture that might label her as less than, and he returned that life to us.

“Our work is not to become perfect or superhuman—it’s to become ultra-human, as human as humanly possible.”

4. Apply a strength-based lens.

Throughout my daughter’s first year, she didn’t babble like most babies do. Because of this, early interventionists considered her to be functioning at nearly a newborn level. But then we saw a new speech therapist who noted that Fiona greeted her not by saying hi or waving, which she couldn’t do yet, but by making eye contact and smiling. Rather than focusing on all my daughter couldn’t do, the therapist focused on all she could do. Strength-based educators envisioned greater goals for my daughter, and they achieved them—they even got Fiona walking and talking. When we apply a deficit lens to a person, seeing where they’re deficient, we rob them of their full humanity and their full potential. But when we apply a strength-based lens and see what they’re capable of, we can meet people where they are, honor their gifts, and envision what’s possible for them.

5. The point of this life is love.

Modern parenting is often tangled up with the desires of the ego. But the point of parenting shouldn’t be to make little replicas of ourselves, and it shouldn’t be to create high-achieving super-humans. I think the point of parenting is to be leveled. I think it’s to be utterly brought to our knees with a love we have no choice over. The point of life itself is love, and the ridiculous and brave and risky act of love turns our hearts into taffy that stretches across the broad spectrum of human feeling. We hurt, we long, we exalt, we rejoice, and when we do that, we become not superhuman, but ultra-human—as human as humanly possible.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: