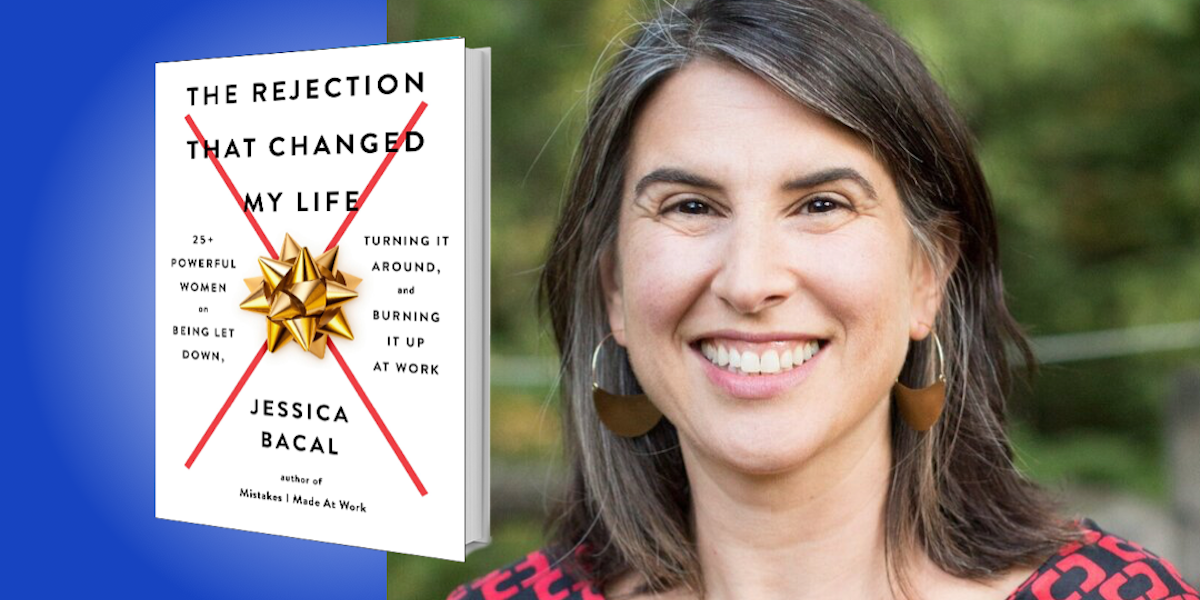

Jessica Bacal directs The Narratives Project, a co-curricular initiative for students at Smith College, where she also teaches a course called Designing Your Life. Prior to Smith, Jessica was a teacher, editor, educational writer and consultant in New York City. Her previous book was Mistakes I Made at Work: 25 Influential Women Reflect on What They Got Out of Getting It Wrong.

Below, Jessica shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Rejection That Changed My Life: 25+ Powerful Women on Being Let Down, Turning It Around, and Burning It Up at Work (available now from Amazon). Download the Next Big Idea App to listen to the audio version—read by Jessica herself—and enjoy Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Rejection is data.

In 2019, I was working at Smith College and loved my job, but I applied for a bigger job at the college. That meant writing a three‑page cover letter with my vision for a new center, giving an hour-long presentation for colleagues, and asking peers for letters of reference. It meant being interviewed by people who already knew me, so after years of normal collegial interactions, we had to sit awkwardly around a conference table so they could assess my potential.

I didn’t get the job.

When I didn’t get it, I felt humiliated because I’d tried so hard in front of all these people. But at the same time, I felt a little bit relieved, which was an interesting thing to notice. That relief, which was about not having to do the job, was important data. Maybe I hadn’t really wanted the job.

Harvard Business School professor Laura Huang told me she categorizes her rejections based on the emotion attached to them, and then looks for patterns in order to learn about herself. For example, the first time Huang was hired as a professor, she got advice to start networking by inviting fellow faculty members and deans to lunch. When she tried this with one especially important dean, the lunch went disastrously; the conversation was stilted and self-conscious. Afterward, she felt embarrassed and rejected.

But Huang paid attention to her emotions and used them as data about herself and about what worked for her when it came to networking. She realized that in getting to know people at work, it felt better for her to join a committee or find another low-key strategy where she didn’t have to invite someone to a one-on-one lunch.

“Laura Huang told me she categorizes her rejections based on the emotion attached to them, and then looks for patterns in order to learn about herself.”

Another way in which Huang uses rejection as data is when she sends out articles for publication. When she was first submitting to journals, she’d make a note of every rejection, writing the name of the article, and the names of her co-authors. She hung them on her wall. And Huang started noticing a pattern: Papers that she wrote with seasoned, well-published colleagues were actually more likely to get rejected, while those she wrote with colleagues at her same career level did better. She was able to use this data to change her publishing strategy.

2. You can build muscles for dealing with rejection.

When going after something you really want, it’s common to face repeated rejection. With time, you can actually get good at it. One of my favorite stories is from a young woman named Caitlin Kirby. She’s an environmental social scientist, and she went to her dissertation defense wearing a skirt made of rejection letters. These were all letters she’d gotten as she pursued her doctorate—rejections of articles she’d submitted, grants proposals, and the like. Kirby told me she’s not a crafty kind of person, but she made the skirt partly to the show other students in her department that rejection is normal on the path to getting a PhD. She wore those letters as a kind of badge of honor.

Kirby told me that she thinks of rejection tolerance like a muscle, because increasingly she’s able to face disappointment with strength. It gets easier over time, though it’s never truly painless. Just as muscles hurt after a new exercise, rejection after a new risk can be painful again.

3. Rejection can make you more creative.

Social scientists are learning that rejection can make people more creative. One of my interviewees, Andie Kramer, had a great metaphor to explain how this works. She said, “If you walk into the wall, fall down, and then try to walk through the same part of the wall again, you’re just going to fall again. You’ve got to look around and say, “Is there a door? Is there some other way that I can get through here? What can I learn from hitting the wall?”

“She thinks of rejection tolerance like a muscle, because increasingly she’s able to face disappointment with strength. It gets easier over time.”

Ally Einbinder, a bassist for the LA punk band Potty Mouth, told me about being dropped by the management she and her band had been relying on. In the music business, Einbinder said, “everyone has an idea about what’s best for you, and because you become fatigued by all the decisions, it’s easy to rely on a management company to make them.” But after this major rejection, she was proud that the band “figured out how to get the album done, release it, and create a marketing campaign within a year.” They did all of that creative work. And after the album came out in 2019, LA Weekly called Potty Mouth the best punk band in LA.

4. Rejection can set you on new and interesting paths.

Many of the women I spoke with talked about how a rejection had set them on a new path. They used a work rejection as a way to pivot. One especially instructive story is from the journalist Carolina A. Miranda. She was working at Time magazine where, she told me, “I might be interviewing Scarlett Johansson one week and rounding up al-Qaeda cases the next.” But she said it wasn’t an ideal fit for her. Because it was a national magazine, they were always asking, “Is this a story of national importance?” And Miranda was interested in “quirkier stuff,” she told me, “and in culture.” Not many of her pieces got published.

Eventually, she left Time and began freelancing and blogging. She sold some articles, but she said that her own blog gave her “a more developed eye in finding unusual stories.” She said, “It also gave me a platform to publish weird stuff if I couldn’t sell it.” Miranda developed a small following, and editors started seeking her out. Eventually, this path landed her a job as an arts and culture writer at the Los Angeles Times.

“Many of the women I spoke with talked about how a rejection had set them on a new path. They used a work rejection as a way to pivot.”

But it’s not as if Carolina thought, back when Time wasn’t taking her pieces, “Oh no problem, I’m fine with rejection because it’s going to set me on a new path!” No, she was disappointed. Many years later, however, she realized that it was a formative experience. In addition to learning a ton, it was a jumping off point. From there, she took a new path.

5. Find support, and share your story.

There’s value in sharing our work rejection stories, and in seeking support. Too often there’s shame associated with rejection. When something bad happens in our work lives, there’s a tendency to assume we’re alone, that nothing like what happened to us has happened to other people. There’s even a psychological term for this: pluralistic ignorance. But during my interviews, I heard that when people were willing to be vulnerable and open, to admit they were struggling, they often were able to form important relationships that buoyed them, lifting them up in both work and life.

One example came from reproductive justice activist Loretta J. Ross, who told me about getting over a major work disappointment. In the nineties, Ross relocated from DC to Atlanta for a job with a mentor she deeply admired. However, within a year, she made a major misstep and was fired. She told me, “I was in shock because I didn’t know what I was going to do next.” So she took a road trip. There was a tribute conference planned in Boston for the poet and activist Audre Lorde, who was sick with cancer. Ross got in her Toyota and drove north, picking up three friends along the way.

She recalled, “In Boston, we met with Audre and celebrated her life, and it put things in perspective.” She also felt comforted by being with like-minded peers and told me, “I was fortunate to have that Black feminist community coming from around the country. It was an emotional reset because I felt that I still had worth—I still had something to contribute.” By the time Loretta Ross returned to Atlanta, she’d been offered another job and was ready to take it on. Sharing her story with other women, finding support, allowed her to do this.

To listen to the audio version read by Jessica Bacal, and browse through hundreds of other Book Bites from leading writers and thinkers, download the Next Big Idea App today: