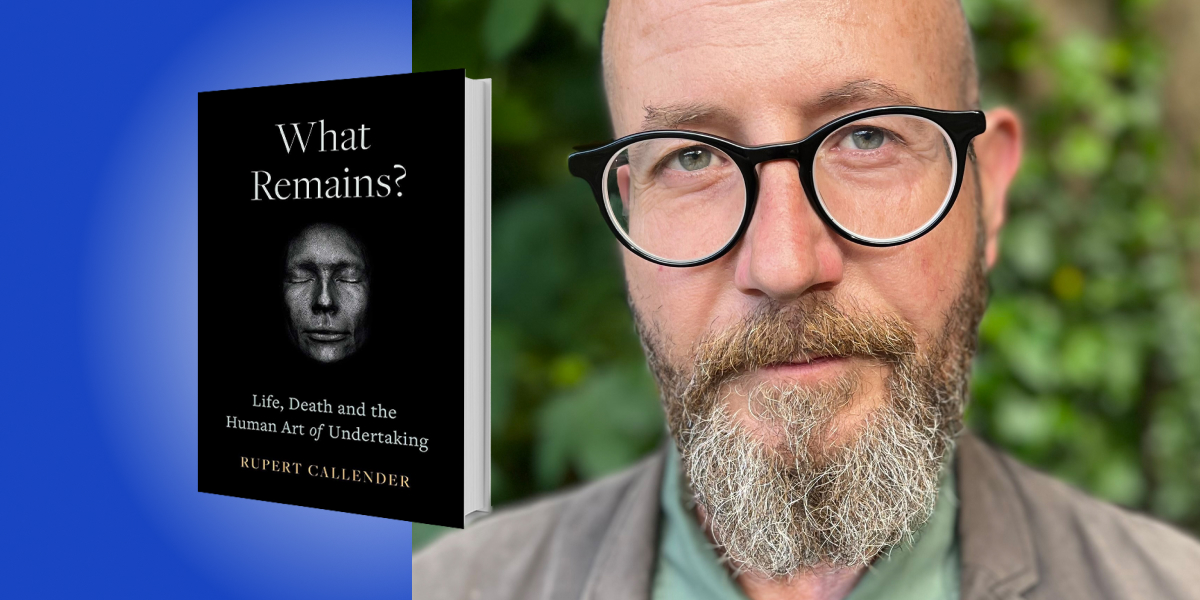

Rupert Callender is a self-taught ceremonial undertaker since 1999. He pioneered a new, radical approach to funeral services, and continues to promote a new way of laying our deceased to rest through his business, The Green Funeral Company.

Below, Rupert shares five key insights from his new book, What Remains?: Life, Death and the Human Art of Undertaking. Listen to the audio version—read by Rupert himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Starting something by knowing what not to do is often a better place to begin than knowing what to do.

I never imagined in my wildest dreams (or nightmares) that I would make my living with the dead. It was not on my radar as a career idea, but a childhood and early adulthood saturated in bereavement meant that I had a lot of experience with grief—most of it detrimental.

I didn’t go to some of those funerals, and the ones I did attend just didn’t work on any level. So, when I found my vocation I knew straight away what I wasn’t going to do. I wasn’t going to wear a weird suit all the time. I wasn’t going to adopt the mock salubrious persona of many funeral directors. I wasn’t going to have a fleet of shiny cars, or ruthlessly up-sell coffins and “stuff.” I wasn’t going to use professional pallbearers to carry the coffin. I wasn’t going to embalm bodies and cover them in makeup. I wasn’t going to steer families into any kind of ceremony that didn’t completely chime with their values and beliefs. I wasn’t going to gatekeep the bewildering experience of grief from the people whose actual loss it was.

This certainty about how I was not going to do it propelled me in the direction of how it needed to be done. And I knew this because it had been done wrongly to me.

2. Do it yourself.

Long before Nike adopted it as their slogan, Jerry Rubin, political leader of the Yippies (Youth International Party) was telling people to do it!

If you have an idea, a radical idea to change things, then don’t wait until the time is right, or you have enough resources, or you’ve thought it through, because you’ll think the guts out of it. Jump in blindly because if you are thinking it, then someone else is already thinking it too. Also, if it’s about change, then the opponents of change will also be saddling up.

“If you have an idea, a radical idea to change things, then don’t wait until the time is right, or you have enough resources, or you’ve thought it through, because you’ll think the guts out of it.”

In the UK, you don’t need any qualifications to become an undertaker because families are not required to use an undertaker if they have the courage to do it themselves.

The first dead body I touched was the first funeral I did. It remains one of the most complex funerals I have ever done, and I’ve since done hundreds, but at the time I had no practical experience organizing any of it.

The ideology that we formed from that experience was to help families do it themselves. Not necessarily all of it, but to encourage radical participation in the practical and ceremonial aspects of a funeral. Get involved. No tourists, all of us fellow travelers on the mortal road.

3. Find your social ancestors.

Everyone is obsessed with their personal genealogy and the internet is bristling with ways to access censuses and records to find out what your great-great-grandmother did.

And DNA technology means you can reach even further, deciphering the origin of every drop of blood within you, tracking your ancestry across continents and millennia. You can even discover what early species of hominin you share ancestry with.

Knowing where you come from gives you an idea as to where you are going and, perhaps, allows for owning the responsibility that goes with any historical damage your ancestors might have done. But for me, it became more important to locate my social and cultural ancestors. By social and cultural ancestry, I mean the artists and writers who have inspired you, the musicians and idealists who have shaped you far more than your genetic family. They might be fictional characters from a novel or film, but you will also discover that some are your elders, peers, and friends.

“Once you find your social ancestors, you can put into practice a form of ancestor worship that is more grounded in the real world.”

For me, I saw the lineage from acid house back to the hippies, the beatniks, back further to the radical dissenters of the distant past. I realized my youthful tribe was part of a much older and bigger tribe. Once you find your social ancestors, you can put into practice a form of ancestor worship that is more grounded in the real world. It even gives you the opportunity to thank some of them personally, which is so much better than saying nice things over their dead body.

4. Create original rituals.

You don’t have to believe in anything to perform rituals. Rituals themselves create meaning. By doing them you open space for a lightly held, playful form of spirituality that owes more to art and imagination than belief.

In What Remains, I talk about some of the rituals I created to shuck off the accumulation of grief that goes with my work. These include making crop circles in the middle of the night, dancing ecstatically into the dawn with friends, and dabbling in psychedelically tinged, offshoots of Chaos Magic (a form of magic that is about the immediate creativity in a particular moment), rather than following complicated instructions from arcane magical traditions of the past. It is spontaneous and disposable, but it focuses the mind’s attention on goals and can become a form of secular prayer.

“Rituals themselves create meaning.”

Some of the best rituals happen naturally. I like eating Jelly Babies while driving, but I don’t like the green ones, so a little pile of green babies started to grow on the passenger seat. Throwing them in the trash bin felt wrong because something about them was like a representation of me as a human, however basic, not to mention it being a waste of food. So, I hit on the idea of throwing them one by one into the verdant hedgerows that line the roads where I live. I only throw them in a beautiful place, no truck stops, or parking lots. They become offerings twice: first as food for mice and slugs, and as a form of nature worship, a little green man thrown into the symbolic mouth of the big Green Man.

5. See your own strength through the lens of others.

When I was an idle youth, I decided that our personalities are of little use to us, but they are incredibly useful to others. We see qualities and strengths in our friends that they themselves are often blind to, yet struggle to spot the equivalences in ourselves.

We are social animals that, in the right conditions, bring out the best in each other. A death might not seem like the right conditions, but after helping countless families through the worst thing that has ever happened to them, I am endlessly astonished at the courage and heart and love of so-called “ordinary” people when faced with the terrible pain of loss. People, like you and me, rise unexpectedly to face the unimaginable.

And it is not just the people going through it, but the community around them which often comes together to help in small, practical, but vital ways.

When you doubt yourself or can’t find the courage that others show, try remembering that one day your strength and emotional integrity might be equally inspiring to someone else. We complete each other and reflect our best selves back to us through the mirror of strangers.

To listen to the audio version read by author Rupert Callender, download the Next Big Idea App today: