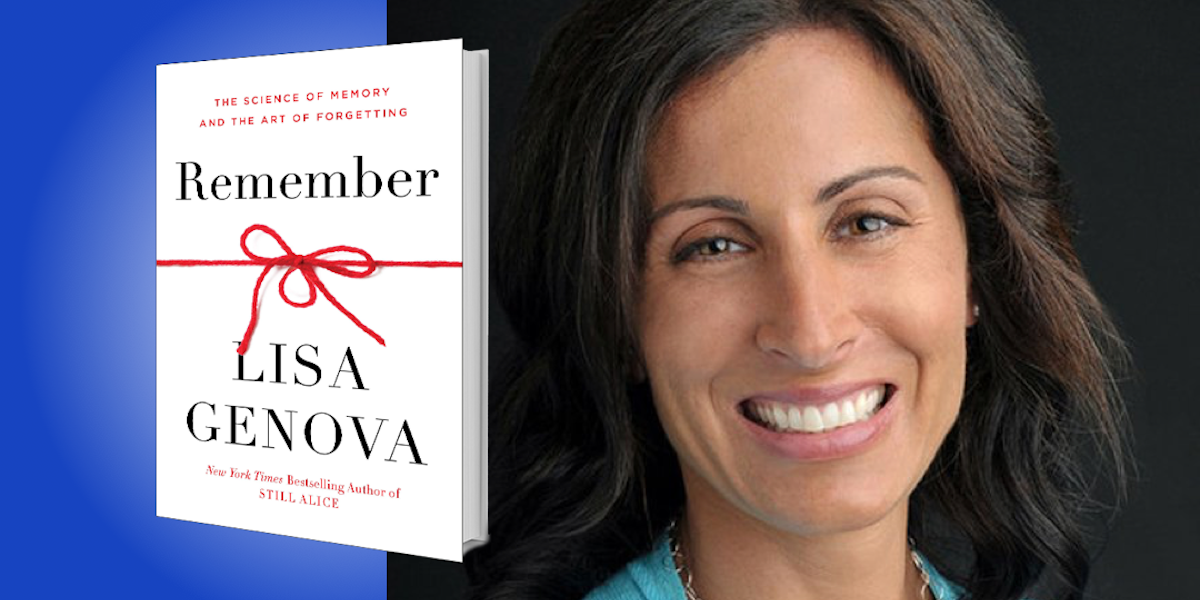

Harvard-trained neuroscientist Lisa Genova has been called the Oliver Sacks of fiction and the Michael Crichton of brain science. She’s the author of four novels, including Still Alice. She has appeared on The Dr. Oz Show, Today, PBS NewsHour, CNN, and NPR, and her TED talk, “What You Can Do To Prevent Alzheimer’s,” has been viewed more than five million times.

Below, Lisa shares 5 key insights from her new book, Remember: The Science of Memory and the Art of Forgetting (available now from Amazon). Download the Next Big Idea App to listen to the audio version—read by Lisa herself—and enjoy Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Where did I put my phone, my keys, my glasses, my car?

The number one reason for forgetting what someone said, the name of a person you just met, or where you put your phone is lack of attention. If you don’t pay attention to where you put your glasses, you can’t form a memory of where you placed them. Later, when you’re unable to find them, you’re not actually experiencing a memory problem; you’re suffering from a symptom of distraction.

Want to improve your memory? Stop multitasking, and pay active attention to what you hope to remember. When you maximize attention, you maximize your ability to remember.

2. Oh, what’s his name?

“Blocking” on a word, also called “tip of the tongue,” is one of the most common experiences of memory failure. You’re sure you know some elusive word, most often a proper noun, but you cannot for the life of you retrieve it on demand. Why does this happen?

Blocking occurs when there is weak activation of the neurons that link up to the word you’re looking for. You often come up with a loosely related word, something similar in sound or meaning. These related words are, unfortunately, called “ugly sisters”; even more unfortunate, zeroing in on an ugly sister will unwittingly make the situation worse. I recently asked my boyfriend, “What’s the name of that famous surfer—Lance? No, it’s not Lance.” He knew who I was talking about, but he couldn’t come up with it either. We were both stumped. It turns out that by blurting out the wrong name, I’d sent my boyfriend’s brain to Lance Armstrong, the ugly sister. Now he was stuck in the wrong neural neighborhood and couldn’t get out.

“Don’t trust that you will remember later what you plan now, because you probably won’t.”

Much later, once we’d stopped trying to find the name, it bubbled to the surface, seemingly out of nowhere: “Laird Hamilton. Yes! That’s it!” Why does that happen? By calling off the hunt, your brain can stop perseverating on the ugly sister, giving the correct set of neurons a chance to be activated. Having a word stuck on the tip of your tongue is a normal glitch in memory retrieval, a by-product of how our brains are organized. You wear glasses if your eyes need help seeing, so you have my permission to use Google if a word is stuck on the tip of your tongue.

3. What doctor’s appointment?

Prospective memory is your memory for what you need to do later. This is your brain’s to-do list, a memory to be recalled at a future time and place. And it is fraught with forgetting because our brains are terrible at remembering to remember. Between 2005 and 2013 in the U.S., surgeons forgot 772 surgical instruments—scissors, scalpels, gloves—inside the bodies of their patients! Prospective memory is unreliable no matter the stakes.

So don’t trust that you will remember later what you plan now, because you probably won’t. Think of to-do lists, check lists, calendars, and pillboxes as glasses for your prospective memory. There is no shame in using these; even pilots use checklists to make sure the wheels of the plane are down before landing. Thankfully, they don’t rely on their prospective memory.

4. Why did I come into this room?

We all experience walking into a room only to scratch our heads in dumbfounded wonder: “Why am I here?” Why does this happen? Because memory retrieval is easier, faster, and more likely to be successful when the context of recall matches the context that was present when the memory was formed.

“If you want to remember more of what happened in your life, step out of your routine. Look for ways to make your days and nights different and meaningful.”

The other night as I was settling into bed, I realized that I didn’t have my glasses, and that I probably left them in the kitchen. I went downstairs, walked into the kitchen, flicked on the lights, and looked around, totally stumped. I had no idea why I was in the room. In this example, the memory for what I wanted—go to the kitchen to get your glasses—was encoded in my bedroom, surrounded by a specific context and cues: bedtime, the book on my nightstand, the books in my bookcase. When I arrived in the kitchen, there was nothing to remind me of what I wanted. And what’s more, these kitchen cues actually misdirected the hunt, sending me down neural pathways associated with cooking and eating, neural circuits that would not lead to reading glasses.

So the next time you walk into a room and stop cold because you cannot remember why you went in there, don’t freak out. But don’t just stand there trying to muscle the answer into your consciousness, either; your brain doesn’t work that way. Go back to the room you were in before, either literally or in your mind’s eye. Revisit the context, and it will most likely deliver the answer to you.

5. You remember your first kiss. Why not your tenth?

Episodic memory is your memory for what happened in your life. Some experiences stick, while others slip away. How can we have such readily retrievable memories for some life events, and absolutely no memory for others? It’s because much of our waking hours are, well, boring. We shower, brush our teeth, drink coffee, do our jobs, eat, watch TV, spend too much time on social media, and go to bed. These utterly forgettable moments are the mundane, habitual events of our daily lives. Sameness is the kiss of death to memory. These experiences don’t make it past the present moment—and that’s okay. Would your life truly be improved if you could remember the details of every morning shower?

While our brains are terrible at remembering what is boring and familiar, they’re phenomenal at remembering what is meaningful, what is emotional, and what surprises us. If you want to remember more of what happened in your life, step out of your routine. Look for ways to make your days and nights different and meaningful.

To listen to the audio version read by Lisa Genova, and browse through hundreds of other Book Bites from leading writers and thinkers, download the Next Big Idea App today: