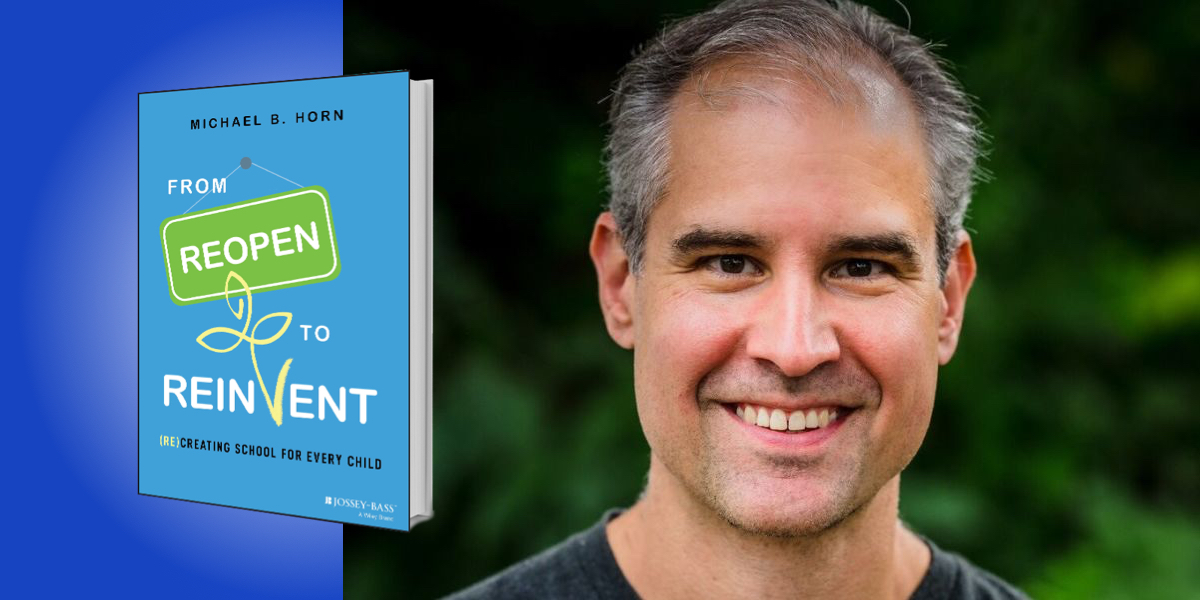

Michael B. Horn is the cofounder of the Clayton Christensen Institute, a non-profit think tank, and the author of many books on the future of education.

Below, Michael shares 5 key insights from his new book, From Reopen to Reinvent: (Re)Creating School for Every Child. Listen to the audio version—read by Michael himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Think positive sum, not zero sum.

Our school structures are built on a historical legacy of sorting students out of the education system. This stems from a scarcity mentality—that there are only a few opportunities, so we must select those students who will benefit the most and discard the rest. Although this arrangement was once successful for society, in today’s knowledge economy—which prizes intellectual capital and works best when all individuals can develop their human potential—sorting no longer suffices. Nor is it necessary, given that today’s technology allows us to personalize learning in unprecedented ways. Opportunity is now abundant.

For instance, at Santa Rita Elementary School in the Los Altos School District in California, a fifth-grade student started the year at the bottom of his class in math. He struggled to keep up and considered himself one of those kids who would just never quite “get it.” In a typical school, he would have been placed in the bottom math group—because the system is built to sort, not support, students. That would have meant that he would not have taken algebra until high school, which would have negatively impacted his college and career choices.

But his story took a less familiar turn. His school transformed his class into a blended-learning environment in which students not only learned in person but also used some online learning. After 70 days of using Khan Academy’s online math tutorials to fill the gaps in his learning, Jack started accelerating. He went from a student well below grade level to one working on material well above grade level.

“A better path is a positive sum education system, which holds that when individuals achieve success, the pie grows larger for all of us.”

Today’s traditional school system reflects a zero-sum view of the world, in which it’s assumed that resources are scarce and for every winner there must be a loser. By age 18, the vast majority of students have already been told that they rank “below” the top, and they’ve been labeled as “not good enough” for certain pathways. That’s devastating, not only for individual students, but for all of us.

A better path is a positive sum education system, which holds that when individuals achieve success, the pie grows larger for all of us. This is the logic that led to the rise of capitalism and an unprecedented growth in prosperity. We ought to view schooling not as a game to be won, but as an effort to help every individual thrive and be productive.

2. Guarantee mastery and student success.

Under today’s school system, time is held as a constant and each student’s learning is variable. Students move from concept to concept after spending a fixed number of days, weeks, or months on the subject. Educators teach, administer tests, and move students on to the next unit regardless of an individual’s results and understanding of the topic.

Contrast this with a mastery—or competency-based—learning model in which time becomes the variable and learning becomes guaranteed. Students only move on from a concept once they demonstrate mastery. Success is part of the model.

As Sal Khan points out, this is more logical because you’d never build a house the way we educate students. Imagine, Sal says, that a contractor says, “You have a total of three weeks to build a foundation, do what you can.” The contractor does what he can. Maybe there are delays. Maybe some of the supplies don’t show up on time. Three weeks later, the inspector says, “Well, the concrete’s still wet over there. That part’s not up to code. It’s 70%. That’s a C. Let’s go build the next floor.” You can imagine how this would go. The more we build up, at some point there’s going to be a big collapse.

But what’s more, the traditional time-based system signals to students that it doesn’t matter if they stick with something because they’ll move on either way. This approach undermines the value of perseverance, a growth mindset, and curiosity, as it doesn’t reward students for continuing to work on a topic. This demotivates students, as many become bored when they don’t have to work at topics that come easily to them or when they fall behind because they don’t understand a building-block concept.

Contrast that to a mastery-based learning system, in which failing initially is fine. Failure is an integral part of learning. Students stick with a task, learn from failures, and work until they demonstrate mastery. For core knowledge and concepts, success is both required and guaranteed. Mastery-based learning systematically embeds values (like perseverance) into its design. It showcases a growth mindset, because students can improve their performance and master academic knowledge, skills, and habits of success.

3. Teachers shouldn’t grade students.

It’s as American as apple pie. Teachers grade their students. But what if, like the sugar in apple pie, being graded by your teachers isn’t good for students—or teachers, and maybe even society?

“The traditional time-based system signals to students that it doesn’t matter if they stick with something because they’ll move on either way.”

In her bestselling book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Carol Dweck wrote, “When teachers are judging [students], [students] will sabotage the teacher by not trying.” Why would students get the impression that their teachers are judging them? Because their teachers grade them—which involves judging how well they have done.

One reason there’s so much tension between parents and teachers over grading is that students are stuck in a high-stakes, zero-sum system that parents rightly perceive as averse to failure. Moving to a mastery-based learning system allows for embracing failure as part of learning.

Even in a mastery-based learning system, however, teachers doling out the final grades still creates a conflict of interest that is unfair to both students and teachers. On the one hand, teachers are responsible for students’ learning. On the other, they are responsible for ensuring students’ grades show what the student has done. Teacher grades, for example, are subject to grade inflation. That’s one reason standardized tests have stubbornly remained a part of education—they serve as a check on teachers going easy on their students.

Groups of schools ought to join together to agree on what students should master and rubrics through which students could demonstrate that mastery. Then teachers could grade each other’s students to erase the conflict and create interrater reliability. This is worth a serious investment in time, thought, and building educator capacity because students deserve schools where teachers are their advocates. Teachers deserve the same.

4. The T in Teachers should stand for Team.

We ask an impossible number of things from teachers. Even before the pandemic, 30% of college graduates who become teachers typically leave the profession within six years. That ranks as the fifth-highest turnover by occupation, behind secretaries, childcare workers, paralegals, and correctional officers. Creating a more sustainable and gratifying teaching profession is critical.

“Creating a job in which teachers must serve as a superhero is filled with stress and unsustainability.”

Part of the challenge is that the traditional one-to-many teacher-to-student model is broken. Among the things we ask of a single teacher are content delivery, tutoring, mentoring, facilitating conversations and projects, serving as a concierge to explore different interest areas, curating resources, offering timely feedback on student work, data mining, and counseling.

To do all of this, teachers must act as superheroes. Many ably do, but creating a job in which teachers must serve as a superhero is filled with stress and unsustainability. It’s a path to failure for many. Asking teachers to do things for which they haven’t been trained also creates downside of risks for students.

One change that could significantly help teachers is making teaching a team sport that distributes these crucial roles across several individuals. By team teaching, I’m referring to co-teaching, in which groups of teachers actively work together as they support large groups of students. The most obvious way to accomplish this is to create larger learning environments or combine classrooms. Once you have this set up, teachers can disaggregate their roles. From the Elizabeth Public Schools district in New Jersey (where five schools pioneered the use of Teach to One for math in open spaces of roughly 3,000 square feet) to Summit Public Schools and Montessori classrooms, there are many exemplars in practice today.

5. Make schools friendlier to parents.

A big observation during the pandemic was that schools provide safe childcare for parents. But if schools are about providing childcare, then they aren’t doing a great job—even in normal times. Childcare that lasts from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. isn’t in sync with the conventional 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. workday, not to mention the increasing occurrence of less consistent work schedules. Plus, leaving parents to figure out what their kids should do during summer break is stressful.

While many of us remember summers with nostalgia and fondness, think about what parents go through. One parent told me that she started planning for summer the preceding November. The sign-ups start in early December, and you have no idea what activities your child will even want to do in six months. On top of that, each week of the summer is often different, which creates stress on schedules and childcare.

What if school were year-round? That’s not unheard of in nearly 4,000 schools in America. It’s known as a balanced school year. These schools still offer breaks for students. In one model, students attend school for roughly 12 weeks followed by three weeks of vacation year-round. That creates fewer huge blocks of uninterrupted time for children, lessening the exhaustion that teachers feel at the end of the year as well.

“If schools are about providing childcare, then they aren’t doing a great job—even in normal times. “

And what if school had vastly different schedules that were more flexible? For example, Bob Harris (who used to lead HR at the Pittsburgh public schools) thinks we ought to flip the high school day. In a flipped school day, students would start their day in line with the time teens ought to be waking up—9 a.m. or even 10 a.m.—by reporting to a workplace in their community, which they could rotate every semester or year. After working half a day, the students would break for lunch and head to school for extracurricular activities and projects with fellow students. Finally, in the evenings, students would take their classes online from home when their parents are more likely to be around.

That’s just one arrangement. It’s time to meet parents with what they need as well, so that their children have great care that helps everyone be happier and more successful.

To listen to the audio version read by author Michael B. Horn, download the Next Big Idea App today: