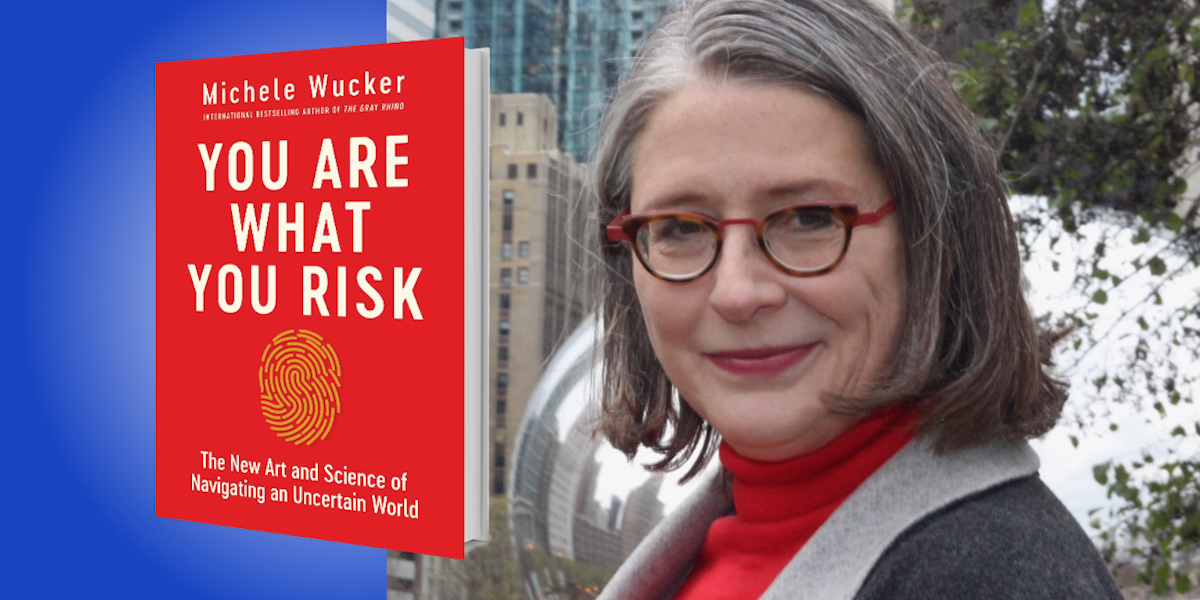

Michele Wucker is a former media and think tank executive who is currently a strategist, speaker, and writer. She has a popular TED Talk, and is the author of four books, including The Gray Rhino, a #1 English-language bestseller in China.

Below, Michele shares 5 key insights from her new book, You Are What You Risk: The New Art and Science of Navigating an Uncertain World (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Michele herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The Risk Fingerprint

The risk choices you make identify you just as distinctively as a fingerprint does. What you choose to risk tells the world about your priorities, your purpose, and your values. It also reflects your personality and influences.

Your underlying personality is the key determinant in what risk choices you make, and while you can’t change your innate traits, you can create habits to smooth out or intensify them. Like a cut that leaves scars, experience can change the way you respond to future risks.

Some of the influences on your risk decisions are temporary but more powerful than you think: who else is in the room, what you had for lunch, and even the temperature or fragrance in the air. Did you know that eating spicy food makes you more likely to take more and bigger risks for a few hours afterward? Or that cooler temperatures may have a similar effect? If you want to ask your boss for a raise, do it over lunch in a Thai restaurant, order your meal spicy, and ask them to crank up the air conditioning.

“What you choose to risk tells the world about your priorities, your purpose, and your values. It also reflects your personality and influences.”

Understanding our risk fingerprints and what creates them is a powerful tool to understand ourselves and those around us. In turn, embracing our risk fingerprints—including both the strengths and weaknesses in our risk relationships—helps us to make better decisions, take smarter risks, and live more successful and productive lives.

2. Risk Empathy

Once you have clear insights into your own risk fingerprint, understanding the risk fingerprints of the people around you can improve your relationships, both personal and professional. In fact, “risk empathy” is key to teamwork and partnership, and applying it can help you to open doors that you might not have known were closed in the first place.

For example: How much time do you leave to get to the airport? This is a great way to understand your own risk preferences and those of the people around you—and hopefully find common ground. Sometimes people who like to get to the gate just before it closes do not necessarily like risk-taking more than people who get there too early; they just have a different way of coping. When you’re traveling with a friend or colleague, understanding why each of you needs more or less time and meeting the other person in the middle can smooth over a lot of arguments.

Risk empathy also involves being aware of and busting up risk stereotypes. Women, in particular, are subject to stereotypes about their risk preferences and attitudes. That costs women founders money from venture capitalists who don’t think they are likely to take “enough” risks, even though the data shows that women are often wiser risk-takers than men. Academic research often reinforces these stereotypes, even when the underlying evidence doesn’t justify the headlines.

“Risk empathy also involves being aware of and busting up risk stereotypes.”

A true risk empath recognizes that someone from a different background may see risk in very different ways from their own, but doesn’t make assumptions. Instead, risk empaths listen to what others say about the risks in front of them and what makes them more or less comfortable with choices—and then put that knowledge to use. Often, differences in risk attitudes between generations or genders or ethnicities are rooted in experiences or environments specific to each group, but not every person in that group may share those experiences. Sometimes people will have honed their risk-taking skills because they had to take more risks because of their environment, and others may be more comfortable taking risks because their social background gave them a fallback. Tapping into those nuances can help us understand natural biases that affect how we see risks, and having a diverse set of perspectives can help us avoid blind spots.

3. The Risk Ecosystem

Our risk choices are part of a feedback loop among the risk attitudes and choices that individuals, organizations, and societies make. A risk ecosystem is the cultural, social, and policy environment that affects how each person and organization responds to risks.

The future not just of organizations but of societies and nations depends on the risk ecosystem that they create. We’ve seen this clearly with the way different countries, cities, and communities have responded to the risk that COVID-19 posed. We’ve heard all different explanations, all of them with some element of truth, for why some countries masked up and others didn’t, why some people took every precaution and others threw caution to the wind. But the real explanation for the differences in how people and societies respond to pandemics and other threats lies in how and why they perceive risks the way they do, and on their ability to fend them off. That is closely tied to the risk ecosystem that they put in place.

“It’s time to stop using ‘risk averse’ and start looking at whether risk decisions are appropriate for the situation at hand.”

Is there a social safety net? Who bears the costs of bad risk decisions and who reaps the benefits? What incentives are there in place to encourage people to take “good risks”—that is, to pursue opportunities—and to deter them from “bad” risk taking—that is, unwise or even dangerous decisions? How do you judge who is worth taking a risk on? How do you price risk properly?

The importance of a strong risk ecosystem is true for organizations, too. Do they promote a culture of conformity and “the way we’ve always done it,” or do they reward creativity and innovation? How they provide incentives for different kinds of risk-taking may unintentionally push people to made decisions that make sense for them in the short term but hurt the organization down the road. Do they see the biggest risk as making a misstep or becoming obsolete?

4. Stop saying “risk averse.”

All too often, we confuse risk awareness with what we call “risk aversion.” Technically, risk aversion is the decision to take less risk, all things being equal. But all things rarely are equal. Is it risk averse to decide to pay down student loans at 10 percent instead of putting your money in a stock market at record highs where you are more likely to lose money than gain it? No, it’s smart. Does walking down a dark alley at 3 AM pose the same risk to a 5-foot woman as to a 6-foot man? No. Are women and men punished the same way for making business decisions that go bad, especially if they are not in a gender typical role? It’s time to stop using “risk averse”—especially since it often is not meant in a flattering way—and start looking at whether risk decisions are appropriate for the situation at hand.

“By being aware of risks and your response to them, you’ve already taken a step toward reducing them.”

We need to focus instead on risk awareness and risk savvy—on making good risk decisions, not just taking bigger or smaller risks.

5. Risk management has to involve our reactions to risks, not just the dangers we face.

After the Great Financial Crisis that hit its depths in 2009, companies rushed to make “risk heat maps” and track all sorts of possible risks. But too often, they did it just to say they did it, and once they had checked “completed risk analysis” off of their list, they didn’t pay enough attention to what they were doing about those risks.

Companies and boards are starting to pay attention to risk governance and behaviors, but the concept of understanding and optimizing your own relationship with risk is something that any person can easily apply to their own lives.

When you include your own risk awareness and skills as part of the decisions you make, you will learn to avoid dangerous missteps even as you become more comfortable stretching to pursue opportunities that might have been too scary. You can set up peer support groups to give you a temperature check on the risks you’re taking—both the active risks, like making a big investment, or the passive risks, like avoiding the “gray rhinos” that you know are in front of you, but you are not heading off for whatever reason.

By being aware of risks and your response to them, you’ve already taken a step toward reducing them.

To listen to the audio version read by Michele Wucker, download the Next Big Idea App today: