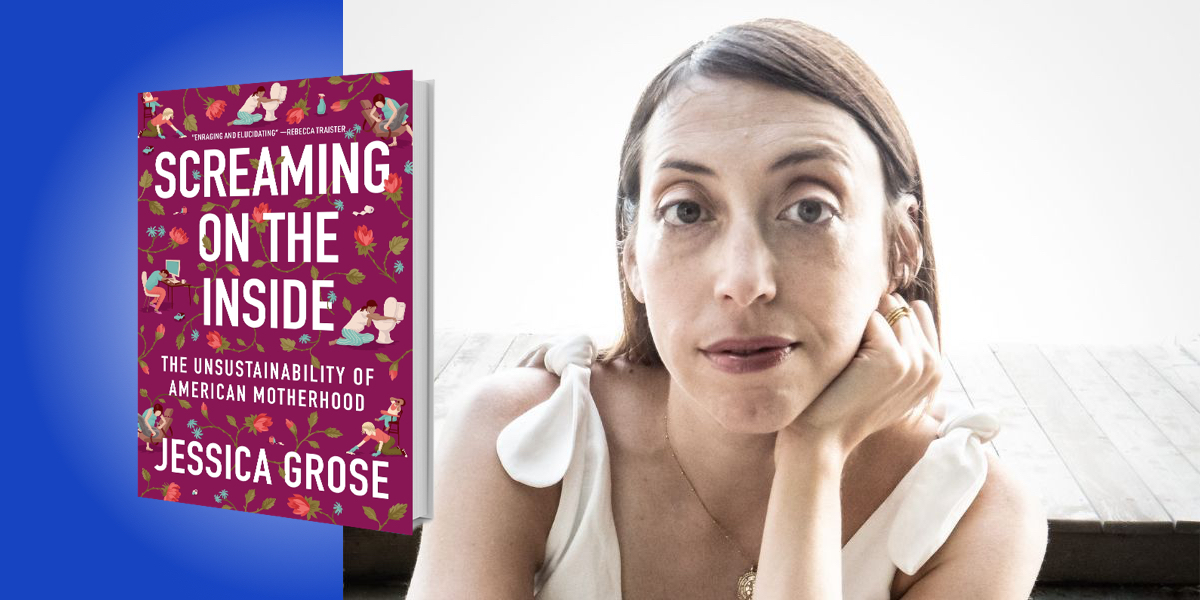

Jessica Grose is an opinion writer at the New York Times. She was formerly a senior editor at Slate, and an editor at Jezebel. Her work has also appeared in the Washington Post, Businessweek, Elle, and Cosmopolitan, among others.

Below, Jessica shares 5 key insights from her new book, Screaming on the Inside: The Unsustainability of American Motherhood. Listen to the audio version—read by Jessica herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. There’s no single right way to parent.

While listening to about 100 contemporary moms, many spoke about how they felt pressured and guilty about not living up to particular unreasonable ideals. While each mother had slightly different concepts of the ideal, these unrealistic notions—usually about being serene and self-sacrificing every second of the day—did not serve them or their families.

Reams of research and history will tell you what all parents need to understand: there is no “right” way to parent. The truth is that parenting cannot follow a recipe. There’s no foolproof set of rules that will result in a permanently happy child. Every parent has different values, and we will have different ideas about how to pass those values along to our children. What successful parenting has in common is not a particular set of rules, but close observation of the kind of unique humans our children are.

2. Ambivalence is human.

Mothers are also human. One of the most damaging parts of the American motherhood ideal is that we aren’t supposed to express anything but perfect love for our children. No one feels perfect love for anything all the time, and it doesn’t make you a bad mother or a bad person to admit that out loud. A piece of advice from my own mother, who is both wise and practiced psychiatry for forty years: Even about the things we love most, we are truly ambivalent.

“One of the most damaging parts of the American motherhood ideal is that we aren’t supposed to express anything but perfect love for our children.”

Ambivalence, in psychoanalytic terms, is not indifference or mixed feelings, as the late psychotherapist Rozsika Parker explained in her book Torn in Two: The Experience of Maternal Ambivalence. Ambivalence means “quite contradictory impulses and emotions towards the same person co-exist. The positive and negative components sit side by side and remain in opposition.” We will feel strong pulls of adoration and rage and every emotion in between. Parker described maternal ambivalence as “normal, natural and eternal.”

The eternal part of ambivalence is key. Sometimes we imagine mothers of the past as more essentially maternal in some way, as if modern life has stripped away the pure joys of motherhood. But when you read women’s diaries and letters from the past three hundred years, that could not be further from the truth. Which leads me to…

3. “Natural” motherhood isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

Many mothers feel guilty because they needed medication while they were pregnant, during birth, or afterwards. Others felt bad because they did not breastfeed for very long, or at all. They felt that the “best” kind of mothering was “natural” which in the current interpretation means without the involvement of modern medicine or commercial products.

Women’s diaries and letters from centuries ago, before antibiotics, antidepressants, or formula were available, document that “natural” motherhood was not a beautiful, earth-mother fantasy. Women from the 19th Century, for example, described giving birth as a “dreaded ordeal,” and a “constant & never ceasing horror.” The mother of a sleepless, colicky infant wrote of the “hard feelings” she had toward her baby son. “I fear I am not very charitable towards babies . . . as I find myself at such times wishing for ‘a lodge in some vast wilderness, where the cry of babies might never reach me more.’” Another woman said the thought of nursing her baby for the rest of her life made her want to “lie down & die.”

4. No country as rich as the U.S. gives as little to parents.

Though there have been tremendous gains for mothers at work in the past fifty years, the United States still does not have federal paid parental leave or consistently subsidized child care. The U.S. often ranks dead last in terms of postpartum coverage for parents, and our peer nations are far more generous—countries like Canada, Estonia, Norway, Sweden and Austria all offer more than a year of paid leave for moms. According to analysis by my colleague Claire Cain Miller at the New York Times, “Rich countries contribute an average of $14,000 per year for a toddler’s care, compared with $500 in the U.S.”

“Our peer nations are far more generous—countries like Canada, Estonia, Norway, Sweden and Austria all offer more than a year of paid leave for moms.”

Because the U.S. does so little to support moms and dads, even parents in two-income families fear financial insecurity. The costs of childcare continue to soar. As one mother who works full time put it to me: “I pay pretty much my rent in day care.” Without additional structural support, parenting in America will continue to feel much more stressful than it needs to be.

5. Parents have always needed help from their communities.

Raising the next generation is too big and important a task to leave for just two parents without additional support. As far back as we can go in prehistory, parents engaged in what biological anthropologists refer to as “cooperative breeding”—which is the idea that family and community members would help with holding, grooming, and sometimes even feeding your baby. Research shows that modern parents fare better when they do not feel alone.

Extended family ties are essential to the well-being of mothers, but “family” doesn’t necessarily have to be people you are related to by blood. The Rapid-EC project, which studied parents of young children during the pandemic, found that high levels of social support can be incredibly protective. Even when families experienced economic hardship, if caregivers reported high levels of emotional support, they were much less likely to report stress. Up and down the socioeconomic ladder, “emotional supports interrupt the chain reaction from material hardship to child emotional distress.”

We lived with my parents in the spring and summer of 2020 so that we could get help with child care when Covid shut everything down. We then decided to live with them again during the summer of 2021. Not out of panicked pandemic necessity, but because we missed each other. I never want to go back to my siloed pre-pandemic life—all three generations of my family benefitted so much from this renewed closeness.

To listen to the audio version read by author Jessica Grose, download the Next Big Idea App today: