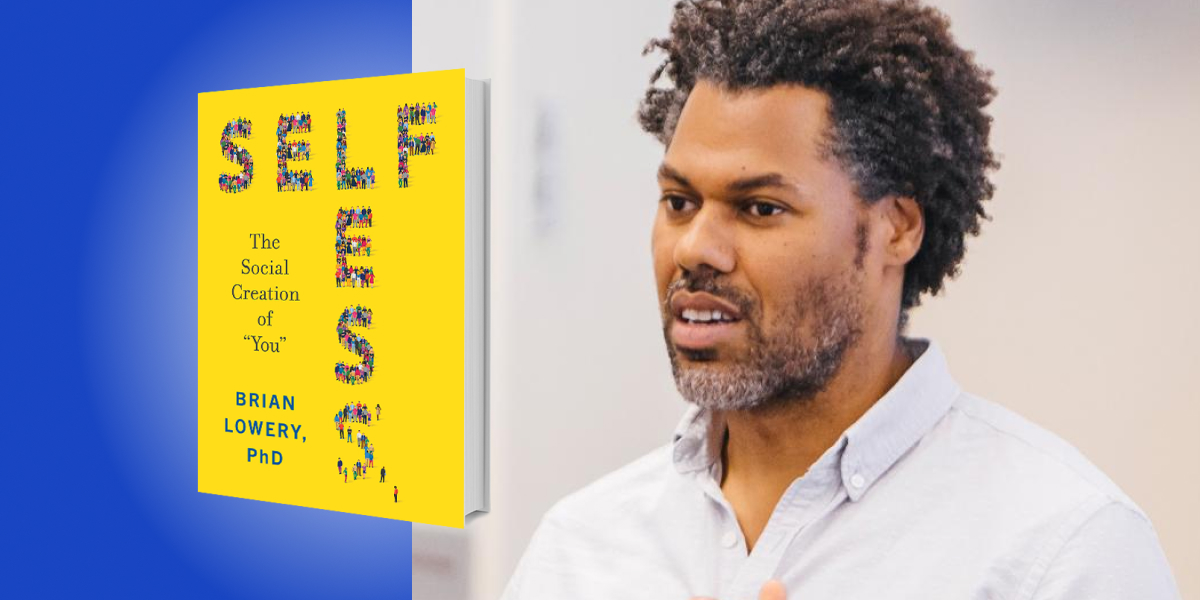

Brian Lowery is the Walter Kenneth Kilpatrick Professor of Organizational Behavior at Stanford University. He received his doctorate in social psychology from UCLA and he is current the Director of the Executive Program in Leadership at Stanford.

Below, Brian shares five key insights from his new book, Selfless: The Social Creation Of You. Listen to the audio version—read by Brian himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Although most healthy people experience the self as inside the body, this is not always the case.

It is important to challenge the way most people understand the self. That starts with understanding the possibility of the self not being where you typically think it is. The self doesn’t need to be in your body. One way that scientists can demonstrate this is by creating the illusion of an out-of-body experience. How do they do this?

Well, they put on a virtual headset and they’d have you see the back of your body as if you’re another person outside of your body. Then they would stroke your back while stroking your avatar’s back at the same time. They then move you from the spot you were standing and ask you return to that spot. What tends to happen is that people move toward the location that seemed to be occupied by the avatar, suggesting that their sense of self drifted out of their body toward the avatar. This is a small demonstration, but it’s important because it suggests that the experience that we tend to have of being inside our body is not a given, and that experience can be altered.

2. You can, and probably do, incorporate other people into your sense of self.

Consider your face for a moment. If you’re healthy, you recognize your face when you see it. When you see a photo or video of yourself, you know it’s you. What’s amazing is that scientists can create an illusion by which you bring someone else’s face into your sense of self. How do they do this?

Similar to the out-of-body experience experiment, they sit you in front of someone else, and then you watch that person’s face being stroked with a feather on the cheek while having your own face being stroked at the same time. After they’ve done that procedure, they show you photos. Some of the photos are just you, some of the photos are the person you saw, but importantly, a number of the photos are a mixture. These photos are also morphed, so that there are photos that are half you, and half the other person, as well as photos that include a bit more of you than the other person and vice versa.

“Psychologists use the idea of including others in the self as a way of demonstrating closeness.”

As you see the photos, you are asked, “Is this photo mostly you or not?” If you’ve had your face stroked at the same time that the other person’s face was stroked, you tend to be more confused when confronted with a face that looks more like theirs. You tend to say it’s mostly you. What this suggests is that you’re bringing their face into your sense of self. This amazing effect demonstrates our ability to expand our sense of self by including others in it.

Psychologists use the idea of including others in the self as a way of demonstrating closeness. A number of psychologists now, primarily Elaine Aron, have demonstrated that people can indicate the degree to which they see their selves as including other people. This can be used as a measure of closeness. It also suggests that not only can we change what people think their self is, we can change what people think they are. That is, we can create a sense that other people’s faces are incorporated into our own sense of self.

3. Social identities are communally created and owned.

We are born into communities, families, neighborhoods, and nations. We’re given identities before we have any say, and these communities define other identities that are available to us and whether or not we can inhabit them. Consider a controversial one at the moment: gender. When you’re born, you have a physical body, but that physical body does not necessarily define your gender. What it means to be a man or a woman, or non-binary or any other gender is determined within a community.

Gender is in how we interact with each other. It’s the ideas that we create in relationships, what it means to be a woman or to be a man is created in our community. Then as individuals, we ask to be accepted as one or another gender. The clothes we wear, the way we carry ourselves or our requested pronouns are all ways that we ask to be seen as our preferred gender. We are making requests to inhabit a communal creation of a particular gender identity.

Then our community or the relationships and interactions we have are opportunities to affirm or deny those identities. From my perspective, you are a woman or you are a man when you exist as a man within your relationships, within your community. Identity is, in part, determined by the relationships we have in our communities.

4. If we think of freedom as being able to say, do, or be what we want without others constraining us, having a self limits freedom.

At this point, it should be clear that I think of the self as constructed within relationships and within communities. The identities we occupy, and the ways we define ourselves, are a function of the relationships we have and how other people see and relate to us.

“It constrains who I am in a way that allows me to understand the world, but it does constrain me.”

I opened this with a description of myself as a Black man, as a professor, and as an author. All of these things exist within relationships. Your reading my book makes me an author. Without a book, without readers, I’m not an author. Now, this constraint can feel very comforting. I understand who I am. I understand what people expect of me, and how people will engage with me. It situates me in the world, my sense of self, my identity. But it comes at a cost. It constrains who I am in a way that allows me to understand the world, but it does constrain me. So, a sense of self can also constrain our freedom.

5. The self can function like a time machine.

Humans are the only creatures we know of that are aware of their own eventual demise. Some social psychologists have theorized that this leads to terror that needs to be managed because we’ve evolved to desire life.

The Terror Management Theory suggests that one way humans manage this is to seek symbolic immortality. For example, when reminded of death, people that don’t believe in an afterlife tend to increase their estimate of how long their national culture will persist by thousands of years. It seems that they’re seeking increased longevity through the part of themselves that are defined by their nation.

In addition to symbolic immortality, the self also helps create a sense that life is meaningful. In research I’ve done, when people believe that their current self will persist into the future, they report an increased sense that life is meaningful. A sense of self may be useful both to help manage the fear associated with our imminent demise, as well as giving our life a sense of meaning and purpose.

Taken together, these ideas suggest that our selves exist in relationships within communities, that our selves are constructed from interactions both intimate and fleeting, that our selves limit our freedom in favor of providing coherence in the face of social chaos, and that our selves provide the possibility of transcendence. Most importantly, this all points to the inability to even be a self alone. There is an interdependence inherent in our humanity and a responsibility we all bear for the creation of each other. Imagine what the world would be if we all saw this more clearly.

To listen to the audio version read by author Brian Lowery, download the Next Big Idea App today: