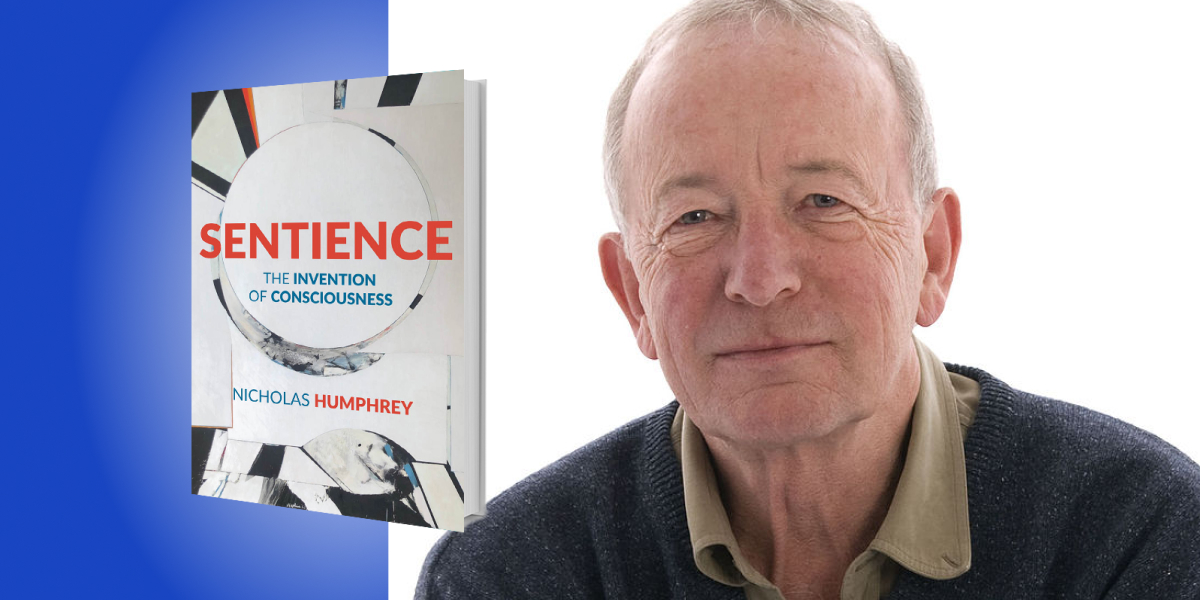

Nick Humphrey is a theoretical psychologist from Cambridge, England who is known for his work on the evolution of primate intelligence and consciousness.

Below, Nick shares 5 key insights from his new book, Sentience: The Invention of Consciousness. Listen to the audio version—read by Nick himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Understanding sentience helps us understand our reality.

This is a book about what matters most in the world: It’s about the nature of sentient experience—what it’s like to be conscious of the sensation of redness, sweetness, or pain. What brings these conscious feelings into existence? Which animals other than humans experience them?

These are questions on which scientists and philosophers are deeply divided.

Some think all living things are sentient; some think only humans are; some believe intelligent machines soon will be sentient; some that sentience is a basic property of matter. They can’t all be right.

We want to discover what the truth is for two reasons. One is simply to fill in the picture of the world around us. It’s intellectually provoking not to know the facts about what lies beneath the surface of other creatures’ lives. We want to lift the veil.

The other reason is a weightier one. We want to know who or what else is sentient, so as to know where our moral obligations lie. Is it immoral, for example, to boil a lobster alive? If the lobster consciously feels pain, then yes it must be. If it doesn’t, then no it needn’t be. We don’t worry about the morality of boiling an insentient cabbage alive. So which is it? Are lobsters sentient or not?

2. Blindsight, and the dissociation between perception and conscious sensation.

How does sentience relate to perception? Let me tell a story. Fifty years ago, when I was a Ph.D. student in Cambridge, a research project changed my life. There was a monkey in our lab, called Helen, who had undergone surgery that removed the visual cortex of her brain. When I first met Helen, a year after the operation, it appeared she had been rendered completely blind. Curiously, there are other animals, frogs for example, that have no visual cortex to start with—and they can see perfectly well. Then, why not Helen?

While my supervisor was away at a conference, I took the chance to investigate further. I sat with Helen and played with her, offering her treats for any attempt to engage with me by sight. To my delight, she began to respond. Within a few hours, I had her reaching out to take a piece of apple that I waved in front of her; within a week, she was reaching out to touch a small flashing light. This was just the beginning; five years later, she was running around a complex arena, deftly avoiding obstacles, and picking up peanuts from the floor.

“A human patient, who had become blind after damage to the visual cortex, could also see in a way he himself didn’t believe.”

A casual observer might have thought her sight had now returned to normal. Yet, I had reservations. It was hard to put my finger on what was wrong. My hunch was that Helen herself still doubted she could see. She seemed strangely unsure of herself. If she was upset or frightened, her confidence would desert her, and she would stumble about as if in the dark again.

In fact, we were on the verge of a remarkable discovery. We discovered later that a human patient, who had become blind after damage to the visual cortex, could also see in a way he himself didn’t believe. He denied he had any visual sensations, but he could still guess the position, shape and color of an object in front of his eyes. It seemed he had unconscious vision. Blindsight, as we called it later.

The discovery of blindsight was theoretically shocking. No one had ever expected there could be any such dissociation between perception and conscious sensation. After ruminating on the implications of this for understanding consciousness, I found myself asking a question out of the left field: if it’s possible to see after losing the capacity for experiencing sensations, then what is the point of having the sensations to begin with? It became the question that’s kept me busy these fifty years: What is sentience for?

3. Evolved Sentience.

Some people say that we’ve no warrant to ask what sentience is for. Why does it have to be for anything? But that’s never made sense to me. As an evolutionist at heart, I’ve always assumed that sentience is a biological trait that arose by Darwinian natural selection. However, a trait can only be selected if it’s useful to the animal that possesses it, if it helps it in the struggle for survival. If sentience has evolved, it can’t just be a superfluous decoration. It must be making a significant difference to how the animal lives in the world.

This may seem obvious when put that way. But it certainly hasn’t been obvious to everyone. As you probably know, there are philosophers who argue that sentience is a purely private phenomenon, that makes no difference at all to how a person or animal behaves in public. They suggest there could in fact be unconscious “zombies” living among us, beings who have no conscious feelings, but who behave in every respect like conscious humans do.

“If sentience has evolved, it must be making a difference that can be detected from the outside.”

Evolutionary theory tells us this can’t be right. And this is the crucial insight that runs through my book. If sentience has evolved, it must be making a difference that can be detected from the outside. If natural selection can see who’s sentient and who isn’t, then presumably so too must scientists be able to, if they look in the right places. So, where should we be looking? Suppose frogs in fact aren’t sentient. What can monkeys—and humans — do with sentience that frogs cannot?

4. Natural Psychology.

In the early 1970’s, Dian Fossey was at Cambridge writing up her doctoral dissertation about mountain gorillas. Dian invited me to visit her camp in the Virunga mountains of Rwanda to observe the gorillas for myself. She gave me a job to do upon arrival. She wanted me to make measurements of the skeletons of eight gorillas that had been killed by poachers and left to decay. The bodies were rotting and full of maggots. I boiled them up in an old oil drum, stripped the flesh from the bones, and set to work to measure them.

What immediately struck me was their huge skulls—huge brain cases. That set me thinking about how intelligent these animals must have been when they were alive. I naturally assumed that gorillas must use their high intelligence to solve all the practical problems of living in the forest.

Once I was able to observe them, however, I was in for a surprise. The fact was the gorillas’ lives seemed remarkably unproblematical. Food was abundant and easy to harvest, with few if any predators. They did little but eat, sleep, and play. As far as I could see, the gorillas had no need for their large brains. In that case, why did they have them? It didn’t make sense. I realized there had to be some crucial feature of their lives I was failing to pick up on.

Then it dawned on me. While the physical environment might not be taxing their intelligence, family life certainly did so. Every day the gorillas faced endless problems in managing their social relationships with other individuals: maintaining friendships, resolving quarrels, standing up to rivals, and so on. To keep ahead of the game, these animals must have to be psychologists. They need to be able to read each other’s minds.

“While the physical environment might not be taxing their intelligence, family life certainly did so.”

We, humans, have a special way of mind-reading: what we do is imagine how we would feel if we were in the other’s place. Perhaps that is how gorillas do it too. But here’s the thing, you can only imagine what it’s like to be someone else if you first know what it’s like to be yourself. For that, of course, you have to be a conscious sentient being.

From working with Helen in the lab, who no longer knew what it was like to see, to working among the gorillas, I was getting a promising answer to the question. What’s the use of knowing what it’s like to see, hear, taste, or feel pain? It allows you to gain psychological insight into other minds.

If frogs haven’t evolved to be sentient, perhaps it’s because in the world of frogs, there’s no call for doing psychology.

5. So who is sentient and who isn’t?

How far does sentience extend in the animal kingdom? We have to set a high bar. According to the evolutionary story, sentience is far from being a primitive characteristic. There are two conditions for it to evolve.

First of all, the animal must have a sufficiently sophisticated brain to imbue sensations with their impressive subjective qualities. Blindsight suggests that this may require a structure like the visual cortex. Next—and crucially important—the animal must lead the kind of life where there’s a real advantage to having a firm sense of self. This self must be founded on the experience of sensations.

This brings me to a conclusion that many people will find surprising—and possibly unwelcome. Sentience is a rather recent evolutionary innovation. By far the majority of animals on Earth have neither the brains nor the use for it. To stick my neck out, I’ll be more specific: I suspect that sentience may not have arrived until the evolution of warm-blooded animals, mammals and birds, around 200 million years ago.

Elephants, dogs, and parrots we can be sure of. Earthworms, ants, and lobsters, not a chance. Octopuses? They are everyone’s favorite for an exotic animal that’s sentient, but the evidence belies it. Octopuses show no signs of reveling in sensation, as say, chimps, dogs, or ravens do. Octopuses also do not have a strong grasp of themselves as individuals, nor of being capable of mind-reading.

Suppose we could in fact genetically engineer an octopus to experience sensations as we do. Their enhanced sense of self—of being me—would make little or no difference to the octopus’s survival. The new genes would be wasted and would soon disappear.

To listen to the audio version read by author Nick Humphrey, download the Next Big Idea App today: