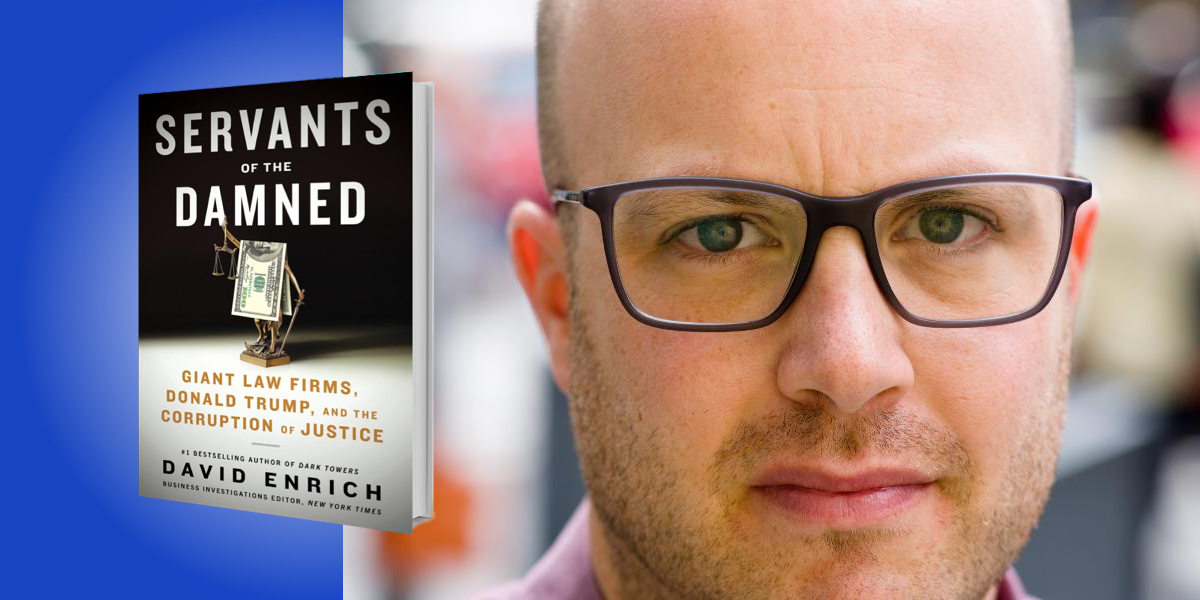

David Enrich is the Business Investigations Editor at The New York Times and has been covering business and finance for nearly 20 years. Previously, he was the financial enterprise editor at The Wall Street Journal.

Below, David shares 5 key insights from his new book, Servants of the Damned: Giant Law Firms, Donald Trump, and the Corruption of Justice. Listen to the audio version—read by David himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The legal industry wasn’t always about short-term victories.

Many people think it’s obvious that lawyers at big corporate firms will go to the ends of the earth to help their clients win. But this wasn’t always the case.

There was a disaster in Cleveland, Ohio in the 1940s. A pair of tanks containing natural gas exploded. An entire neighborhood was leveled. A lot of people were killed, many more were injured, and a ton of property was absolutely destroyed. The company that owned the gas tanks asked its lawyers at Jones Day to figure out what they should do. Jones Day was a law firm in Cleveland that represented some of the biggest companies in the Midwest.

The explosions took place on a Friday. The lawyers spent the weekend researching case law. There were a number of potential ways to handle this. They could try blaming others, like the companies whose materials were used to build the tanks, or the city’s water and sewer authorities because the gas had traveled through their tunnels. The lawyers could downplay the damages the victims suffered. Or they could delay and protract the legal proceedings, hoping that victims would either accept low ball financial settlements or simply give up and walk away.

But after barely 48 hours of studying this, Jones Day lawyers reached a different conclusion. The gas company should admit fault and pledge to make victims whole. So that Monday, the company ran an ad in the Plain Dealer newspaper, inviting victims to show up at their offices. Jones Day lawyers helped set up tables in the lobby and wrote checks on the spot. The community basically forgave the gas company, which operates in Cleveland to this day.

2. The legal industry didn’t exist until fairly recently.

Law firms weren’t always the cutthroat, profit-craze places depicted in movies and TV shows. In 1977, two young idealistic lawyers in Phoenix, Arizona were starting their own legal clinic. It was going to offer cut rate legal services to poor people, the types of services that public defenders wouldn’t provide and that larger law firms wouldn’t bother with. The problem was that the lawyers, John Bates and Van O’Steen, had no easy way to get the word out about their services.

“Lawyers generally weren’t allowed to talk to the media or hand out business cards at cocktail parties.”

At the time, state bar associations prohibited lawyers from advertising their services or otherwise promoting themselves. Lawyers generally weren’t allowed to talk to the media or hand out business cards at cocktail parties. It was all part of an effort to insulate the legal profession from the commercial pressures that existed in other industries.

Bates and O’Steen challenged these rules. They bought a small ad in the Arizona Republic newspaper, letting people know that their clinic would charge only about $75 for a divorce filing, for example. This simple ad was a clear violation of the bar’s rules against lawyer promotions.

The bar association sought to punish Bates and O’Steen. The two lawyers went to court to fight the punishment. They argued that their ad was a form of speech protected under the First Amendment. The case made its way up to the Supreme Court in a case called Bates v. Arizona Bar. The court ruled in favor of Bates and O’Steen, concluding that the First Amendment protected lawyer advertising.

Not only could lawyers advertise their services (hence the ubiquitous highway billboards and radio spots seen and heard today) but they were also free to promote themselves and solicit clients. This set off an arms race for greater geographic reach, more lawyers, more clients, more money, and more power. The legal profession had become the legal industry.

3. Lawyering is mostly about fending off regulations and avoiding taxes.

Lawyering, as it is practiced at giant corporate law firms, is less about protecting clients accused of wrongdoing and more about things like fending off regulations and avoiding taxes.

Take, for example, the small town of Marion, Massachusetts when the Board of Health tried to restrict the sale of flavored tobacco products. The idea had come from a newly-elected public health official, a pediatric oncologist who knew firsthand the dangers of tobacco marketed at kids.

For decades, the tobacco giant R.J. Reynolds had been represented by the law firm Jones Day, which had repeatedly tried to muddy the science about the dangers of smoking and addictiveness of nicotine. Now, as Marion officials planned to restrict flavor tobacco, the law firm rolled out a simple solution. Noel Francisco, who would go on to be the solicitor general in the Trump administration, and at the time was a partner at Jones Day, wrote a four-page letter to Marion’s elected leaders. The letter warned that if they enacted the rules, Jones Day would sue.

“This was a scary threat for a small town, especially since it was coupled with a well-organized lobbying campaign that targeted town officials—even at their homes.”

Legal experts said the letter’s claims were weak at best. Other towns in Massachusetts and elsewhere had enacted similar restrictions. The Board of Health was specifically empowered to take this type of action, they said. But it cost virtually nothing to have a few associates type up a letter, have Francisco sign it, and then send it out in fancy overnight mail envelopes. One former tobacco lawyer at the law firm told me that they did this kind of thing all over the country.

This was a scary threat for a small town, especially since it was coupled with a well-organized lobbying campaign that targeted town officials—even at their homes. Officials in Marion told me that even the letterhead that Francisco had used (it was on thick card stock and listed all of the dozens of offices that Jones Day operated), exuded power and intimidation. The letter worked.

After months of deliberating, town officials decided that they didn’t have the stomach to risk a protracted and expensive legal battle with a global law firm. One town official publicly worried about being tarred and feathered. The proposed tobacco rule was abandoned and the Board of Health official who proposed the idea was so disgusted that he gave up holding elected office.

4. Lawyers rarely get punished when they cross ethical lines.

Jones Day’s work for Abbott Labs, the healthcare company that is a leading manufacturer of powdered infant formula.

Over the years, many families have sued Abbott Labs (the healthcare company that is a leading manufacturer of powdered infant formula) after their babies died or were severely brain damaged following the consumption of their powdered formula. The family of a little girl in Sioux City, Iowa, who was permanently brain damaged, sued Abbott. The family was poor and their lawyers came from small firms. Jones Day pulled out all the stops. It buried the plaintiffs in paperwork and tried placing responsibility on the family for poisoning their daughter.

A federal judge concluded that Jones Day’s lawyers repeatedly engaged in improper legal tactics, including coaching witnesses on how to answer questions during depositions. The federal judge thought that this was part of a pattern in which big corporate law firms abused smaller law firms and plaintiffs. He ordered a Jones Day partner to produce an educational video for everyone at her law firm that would teach them the dos and don’ts of depositions. The judge figured this was the type of unconventional punishment that would get the attention not only of Jones Day, but of the entire corporate bar as well.

“The family was poor and their lawyers came from small firms. Jones Day pulled out all the stops.”

Jones Day, however, appealed the penalty. They argued that the punishment was unfair because the judge hadn’t warned them ahead of time about the specific penalty he might impose. An appeals court agreed, although it did not rule on whether the lawyer’s conduct was appropriate. That decision allowed Jones Day to tell everyone that the judge’s order had been overturned, which was technically true, even if it didn’t have a direct bearing on whether the Jones Day partner had acted properly. The lawyers in this case were never punished.

5. Pro bono work is not always what it seems.

When I started this project, I assumed that pro bono work involved providing legal services to poor people and poor organizations. Though that is true, there’s a lot more to it. Jones Day, for example, does a ton of pro bono work on the U.S.-Mexico border, where it helps migrants navigate the court systems. But the law firm is also doing pro bono work that does not fit the traditional definition.

For example, it has helped deep-pocketed groups fight against things like voting rights. In 2012, Jones Day helped organize a multifaceted legal assault designed to cripple President Obama’s signature legislative achievement, the new national healthcare law. And Jones Day had lawyers working pro bono on behalf of Donald Trump in 2016 and 2017 after he won the election, but before he took office.

A bunch of Jones Day lawyers told me that they had voiced concerns internally. Helping Team Trump didn’t seem to fit the traditional definition of pro bono work, but they were overruled by their higher ups. Jones Day’s defense is that pro bono work is supposed to be for the public good. And well, the public good is in the eye of the beholder. When a big law firm or giant institution boasts about all the good volunteer work they’re doing, well, that’s in the eye of the beholder too.

To listen to the audio version read by author David Enrich, download the Next Big Idea App today: