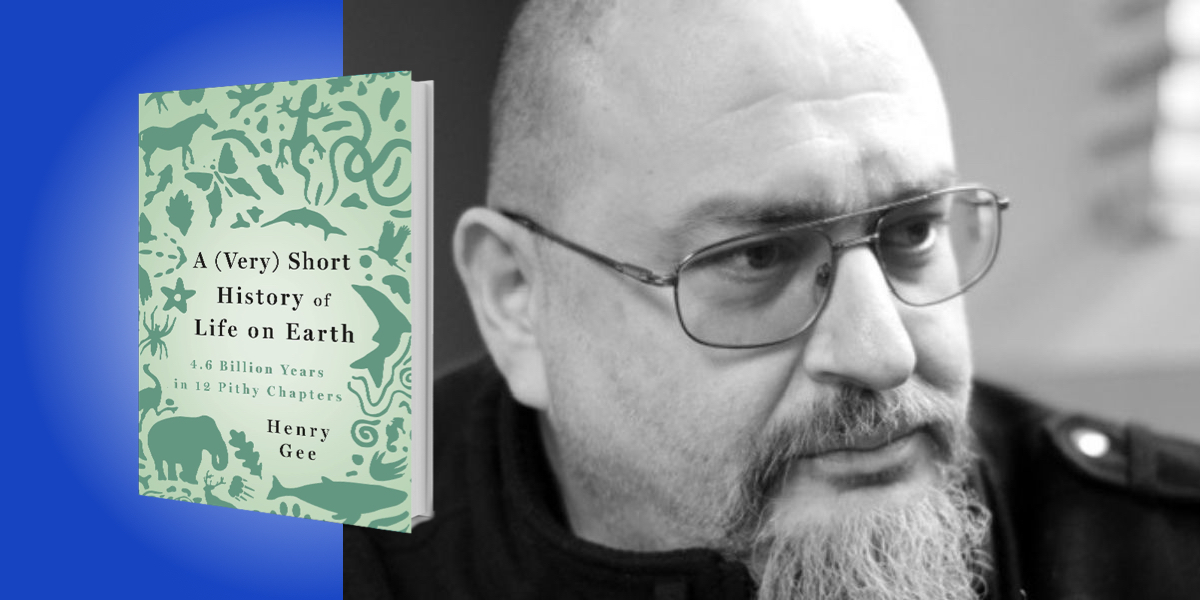

Henry Gee is a senior editor at Nature and the author of several books, including Jacob’s Ladder, In Search of Deep Time, The Science of Middle-Earth, and The Accidental Species. He has appeared on BBC television and radio and NPR’s All Things Considered, and has written for The Guardian, The Times, and BBC Science Focus.

Below, Henry shares 5 key insights from his new book, A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth: 4.6 Billion Years in 12 Pithy Chapters. Listen to the audio version—read by Henry himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Life originated unbelievably quickly.

The Sun, Earth, and Solar System came into being about 4.6 billion years ago. And the first few hundred million years of the Earth’s existence were extremely turbulent—it was a ball of molten magma perpetually stirred up by the impact of comets and even other planets, which stripped off the Earth’s crust and fired it into space, where some of it became the Moon. But soon, all the water vapor in the Earth’s thick atmosphere condensed and fell as rain. It rained for millions of years until the Earth became a world of water, and it was in the depths of the primeval ocean, where jets of superheated, mineral-rich water shot out of the crust, that life began.

The amazing thing is how quickly it began. The first sign of life on Earth is very, very tentative. It’s just the whisper of a shadow of a ghost of a smile in a half-remembered dream, in a tiny but tough crystal of the mineral zircon, dated to 4.1 billion years ago. There’s a tiny smudge of graphite, like the lead in your pencil, that has a chemical complexion suggesting that life once passed that way. And because the Earth is just one of billions or trillions of planets in the galaxy, it’s very likely that simple life exists elsewhere in the universe. The birth of very simple life seems almost inevitable once a planet is formed.

“Because the Earth is just one of billions or trillions of planets in the galaxy, it’s very likely that simple life exists elsewhere in the universe.”

2. If life could have a motto, it would be “whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.”

Many times in the Earth’s history, life has almost been wiped out by cataclysm and disaster. It was cataclysm and disaster that gave birth to life, and on which it has always been nurtured. But there have been occasions in the history of life where life has almost been wiped out, but has evolved and come back even stronger.

The most disastrous episode that we know about was a mass extinction around 250 million years ago, in which 75 percent of everything on land and 95 percent of all creatures in the sea were driven to extinction. The cause? Massive volcanic eruptions, which spewed carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and supercharged the greenhouse effect. Between the acid rain, the mercury vapor, and the ozone layer being destroyed, the planet’s organisms were either boiled, broiled, fried, asphyxiated, poisoned, or dissolved.

But a few million years later in the Jurassic period, life came back even better than before, with a whole host of new, interesting creatures such as dinosaurs and mammals, the group of animals that includes ourselves.

3. Writing about the entire history of life on Earth gives one a dizzying, even terrifying perspective on the passage of time.

It took a while for me to work out how to illustrate this graphically in the book. In the end, I did it with six time charts, and the range of time encompassed by one would be only a tiny fraction of the range of time encompassed by the next. So the first time chart includes the entire history of Earth in the universe, from the Big Bang about 13 billion years ago to five billion years in the future, when the Sun will become a bloated red giant star and swallow the inner planets.

“Human beings came onto the planet hardly a heartbeat ago. And in another heartbeat, we will all be gone.”

The second time chart expands just a tiny fraction of time chart one, running from four billion years ago (the earlier signs of life) to a billion years in the future, when life on Earth—spoiler alert—will become extinct. Time chart three covers a tiny segment of time chart two, and records just the past 500 million years since the evolution of complex life. And so on until time chart six, which looks at a mere 125,000 years from the time that our species first left Africa until the present day. But if you were to place time chart six within time chart one, it would be invisible, microscopic. This gives you a salutary view of the time that human beings have spent on the planet—it is infinitesimal, entirely insignificant. Human beings came onto the planet hardly a heartbeat ago. And in another heartbeat, we will all be gone.

In the grand scheme of things, what will be the human legacy? When measured against the span of life on Earth, nothing. The whole of human history so intense and so brief; all the wars, all the literature, all the princes and dictators in their palaces, all the joy, all the suffering, all the loves and dreams and achievements will leave no more than a layer millimeters thick in some future sedimentary rock—until that, too, is eroded to dust and comes to rest at the bottom of the ocean.

4. This makes it all the more important that we look after the well-being of life on Earth.

While we’re here, we should tidy up after ourselves and leave the place in as pristine a state as we found it. One of the things that makes humans distinct from other animals and organisms is that we are entirely aware of the effects that our activities are having on the planet. We are not like those bacteria which, more than 3.5 billion years ago, worked out how to split the elements of water to create energy, thus releasing molecular oxygen, one of the most toxic and deadly substances in the universe—especially as life on Earth had evolved in its absence. No, we humans are entirely aware of the damage we have been doing to the planet, and therefore, we are morally bound to correct it if we can.

“We humans are entirely aware of the damage we have been doing to the planet, and therefore, we are morally bound to correct it if we can.”

5. There is still hope.

It is not true, as some people might have you believe, that people and governments are doing nothing. In fact, people have been aware of the damage that human activities have been doing to the planet for quite a long time. And the slow forces of government, corporations, and individual decisions—though often halting and going backwards—are beginning to make a difference.

The human population, for example, although still rising, is only rising half as fast as it did at its peak in 1968. By mid-century it could top out, and actually start falling by the year 2100. At the same time, people are becoming much more energy efficient. In the developed world, per capita energy consumption topped out in 1970 and has been declining ever since. In the United Kingdom, for example, per capita energy expenditure decreased by a fifth since the year 2000. Just think of all the ways that we don’t use so much energy anymore—we don’t use those expensive tungsten light bulbs. The internal combustion engine, invented only in the 1870s, will be an antique by 2030 or 2040. So we should take heart.

In fact, perhaps the most important determinant of development in the past 100 years has been the social, political, and reproductive empowerment of women. This has doubled the workforce, made the economy of the world much more efficient, and has resulted in more people being educated and living longer, healthier, more fulfilled lives. 50 years ago, only one in five human beings completed elementary education. Now it’s close to one in two. And although the rate of extinction of animals and plants has increased under human tenure, we are nowhere close to the much-touted sixth mass extinction. We’d have to be doing nothing for another 500 years for that to happen.

So there is hope that we can turn things around and be better custodians of the planet. Therefore, I end the book, “Do not despair—the Earth abides, and life is living yet.”

To listen to the audio version read by author Henry Gee, download the Next Big Idea App today: