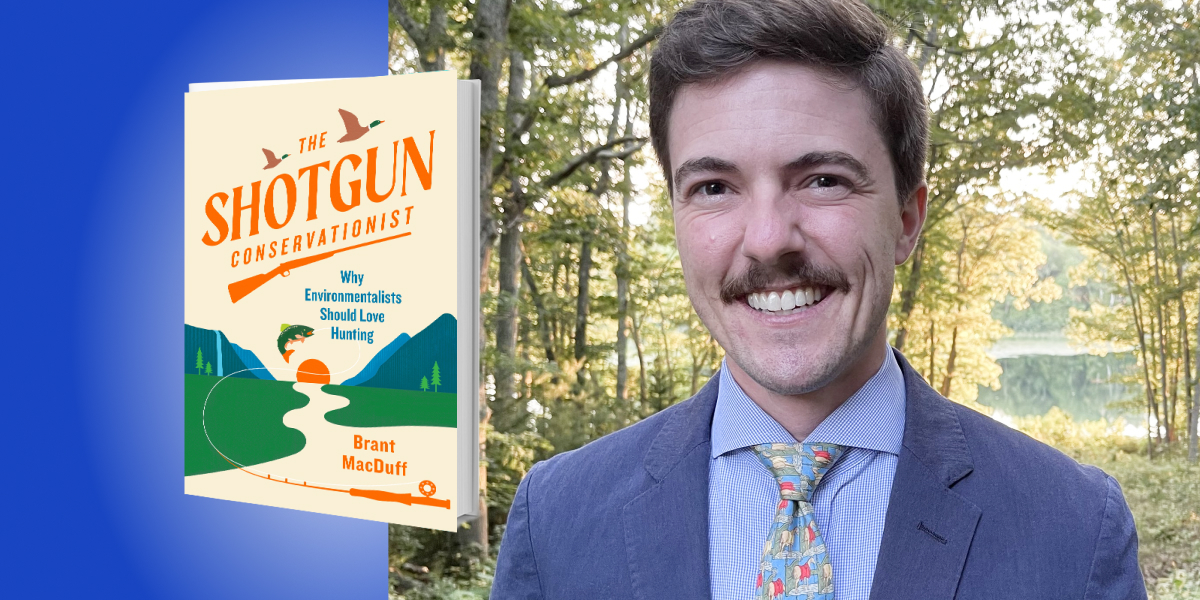

Brant MacDuff is a taxidermist and conservation historian who teaches instructional classes on taxidermy. He also gives tours at the American Museum of Natural History, and lectures on natural history.

Below, Brant shares five key insights from his new book, The Shotgun Conservationist: Why Environmentalists Should Love Hunting. Listen to the audio version—read by Brant himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Hunting prevents the loss of species and habitat.

Hunting requires wild animals, and wild animals require habitat. If the animals that live in a given area are an economic asset, and everyone wants their assets to grow, then the proliferation of species and populations is encouraged. In order for those populations to be healthy and sustainable, they must be managed to a level that gives each individual the opportunity to thrive. That requires unspoiled land for those animals to live on. It doesn’t matter if we are talking about Wisconsin, Mongolia, or South Africa, where individual wild animals have value, their populations and habitats will be valued too.

Most of the time nature only makes money when it’s destroyed: trees are cut for lumber, and the empty land can now be used for human things like mining, drilling, agriculture, and development. When wild animals are the asset, the land must be left as a habitat for them. A forest that is turned into condos stays as condos forever, however, a forest or mountains that are used for hunting animals will be preserved forever. The elk or cape buffalo can be shot annually by paying hunters and those elk or cape buffalo will continue to replenish themselves year after year, as long as they have enough unspoiled wild land to live on. The money that comes from hunting makes it a rare industry that puts the utmost value on leaving habitat alone, or actively working to improve it on behalf of its wildlife.

2. Trophy hunting isn’t bad.

Trophy hunting is a complicated issue to say the least, but in general, it’s not so bad. Hunting both prevents the loss of species and habitat by creating real economic value for wildlife and their habitat. But what is a trophy? The definition is more elastic than you might think. A young hunter’s first squirrel is as much of a trophy to them as the seasoned international hunter’s Mongolian argali ram. However, most people think of big game in Africa when they think of trophies, so let’s stick with that for now.

“The intentions of the hunters don’t matter, only the hunter’s consequences on the environmental economic cycle.”

When people think of big game hunting in Africa, they usually think of rich white guys spending lots of money to hunt impressive species they can show off back home. However, even though those guys do exist, they aren’t the only people who hunt abroad and more importantly, it doesn’t matter if they are. The intentions of the hunters don’t matter, only the hunter’s consequences on the environmental economic cycle. When people are ignorant of that cycle, they don’t see how big game hunting prevents poaching, makes wildlife an asset to the local people who live near those animals, and makes the habitat valuable enough to leave as it is, rather than being converted into something else.

3. Hunters are pro-science.

Hunting has to be pro-science to be sustainable. Not only are hunters pro-science, but they are often science itself. Every time a hunter reports their harvest, they provide valuable data to the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies, whether they realize it or not. They provide data about species’ health, population sizes, migration route fluctuations, and disease tracking. This data has been collected since the 1930s and every year the most up-to-date information is used to determine the latest management regulations to ensure wildlife populations maintain healthy numbers or continue to grow. A government program that must pivot annually in accordance with the latest scientific research is a rare thing, and an exhaustive machine to maintain. However, keeping sustainable wildlife populations in today’s world demands that sort of work, and someone has to pay for it.

When you rely heavily on science, you must leave emotions at the door. That’s why doctors don’t operate on family members—their emotional stake could cloud their better judgment. However, environmentalists that oppose hunting often let their emotions overtake science. They care about the individual animal so much that the benefits of the greater systems at play in conservation science are misunderstood or ignored. The outcome they like or want becomes more important than the outcome that actually works.

“They care about the individual animal so much that the benefits of the greater systems at play in conservation science are misunderstood or ignored.”

Outdoor cats are a prime example of emotion over science. Many people can’t stomach the thought of euthanizing feral cats despite the fact they are widely understood to spread extinction-level disease to wildlife and have directly contributed to the extinction of at least 63 species already. Hunters have hands-on involvement with the cycle of life and death and that imbues a connection to the reality of nature that is more valuable to them than the impossible fantasy of a world devoid of death.

4. There is no bloodless food.

The vegetarian’s bean patty is just as bloody as the hunter’s venison burger and most people don’t know this due to their waning involvement with the natural world. A hunter must take the time to learn the ecology of their surroundings and the biology of the species they hunt if they want to be successful. In other words, they have to be aligned with nature if they want to put meat in the freezer. If you want to put a meat substitute in the freezer, you must ignore, or be ignorant of, the immense toll industrialized agriculture takes on the planet. From habitat conversion, water use, soil death, displacement or deliberate killing of wild animals by farmers or farming equipment, you can’t deny that its production is damaging. Hunters prefer and pay into systems that value wildlife habitat with little to no alteration from humans.

There are too many people on earth now to get all of our meat from hunting. However, between obscuring the toll industrialized agriculture takes on the planet and seeing a hunter proudly display their success in the field, the average person takes away a warped message of what constitutes an environmentally friendly meal. The finished product is mostly what we all see, but if the making of a mass-produced meat substitute was shown beside the making of a wild venison steak, the environmental toll of each would be more apparent, and easily favor the hunter as the more environmentally friendly choice. There might be a dead deer at the end of a hunt, however, that deer’s forest ecosystem will remain and a new deer can only be made by Mother Nature, not a factory.

5. We must pay for wildlife.

It sounds a little silly to say that we need to pay the ocean or bees or the forest or caribou. After all, how do you transfer money to a giraffe? Hunters pay into local systems and international ecotourism economies to keep wildlife and habitat valuable to regional governments and landowners. As long as a habitat filled with animals continues to pay the bills, it can successfully compete with those destructive industries like drilling, mining, agriculture, and development.

“In reality, hunters, by their own choice, are the ones footing the bill for the future of habitat.”

If hunting is outlawed in that region, then it’s up to someone to have an economic system in place ahead of that time to continue funding the region’s wildlife management, scientific monitoring, and forestry. Otherwise, you’ll be left with a defenseless area of land that can’t protect itself against those damaging industries that generate revenue from exploiting it. While hunting might look like exploitation to the untrained eye—picture a hunter next to a dead giraffe—it’s a sustainable form of ecotourism that requires a small human footprint on the landscape. There are growing populations of giraffes in African countries that allow giraffe hunting and shrinking populations in countries that don’t, and there’s a reason for that.

In the US, hunters are often misrepresented as being solely Republican or conservative. That can make hunting issues seem partisan, which is dangerous when hunting regulations end up in front of a voting public. Many of the successful environmental funding structures we have in the US today were put in place by hunters and non-hunters together in the 1930s with the idea of helping wildlife populations rebound and become sustainable. If hunting issues become political instead of environmental, the end of hunting will be the sole desirable outcome without consideration of the economic powerhouses behind it. But it will also lead to wildlife becoming more vulnerable, not more protected.

If we think of the stereotypes associated with US conservatism, like not caring about the environment, or not wanting to pay taxes, it becomes easier to think hunters don’t care about the future of the animals or land they hunt on. In reality, hunters, by their own choice, are the ones footing the bill for the future of habitat. It’s not a good idea to take away a proven form of habitat and species conservation funding without having a system as good, or even better, ready to put in its place.

To listen to the audio version read by author Brant MacDuff, download the Next Big Idea App today: