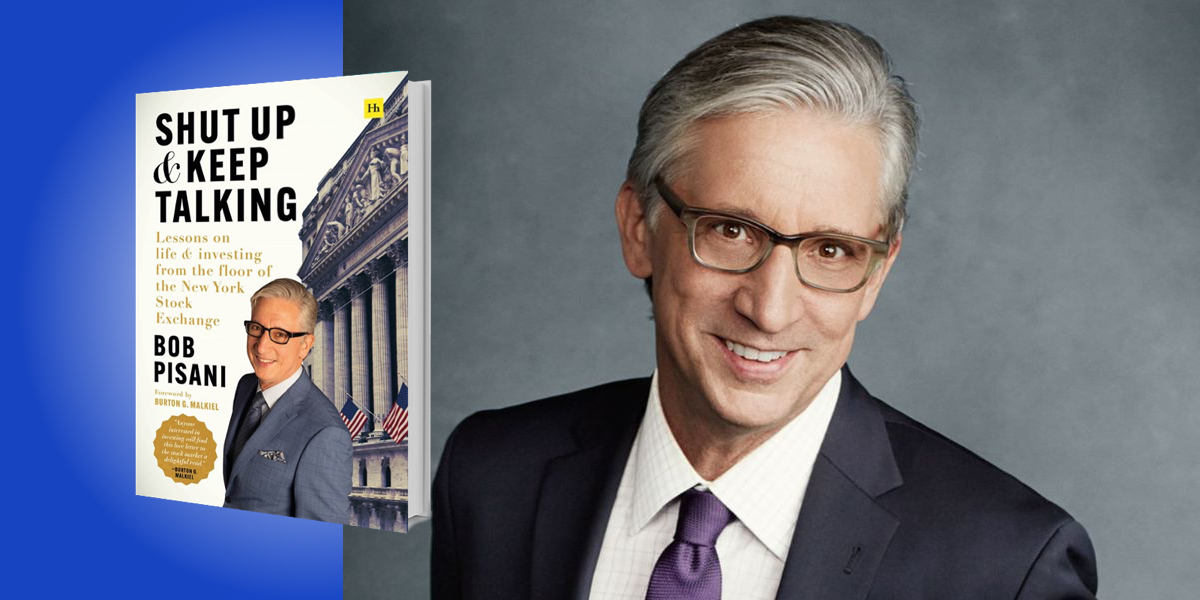

Bob Pisani is the Senior Markets Correspondent for CNBC. He has been with the network for 32 years, 25 of which he spent reporting on the stock market from the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

Below, Bob shares 5 key insights from his new book, Shut Up and Keep Talking: Lessons on Life and Investing from the Floor of the New York Stock Exchange. Listen to the audio version—read by Bob himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Get rich slow is better than get rich quick.

Forget about picking a hot stock and then cashing out. That’s called market timing and it usually doesn’t work because you have to pick the right time to buy and the right time to sell. Almost nobody gets that right. Instead, most professional advisors suggest investing in broad index funds that track the overall stock market, like the S&P 500, and to resist the urge to sell when markets are down. You’re not trying to beat the market; you’re trying to stay with the market because over the long-term the market tends to go up.

That’s what Warren Buffett advises most investors to do. In 1997, he made a bet with a hedge fund manager that over a ten-year period commencing January 1, 2008, and ending December 31, 2017, the S&P 500 would outperform a portfolio of several hedge funds that picked stocks. Buffett easily won: the group of hedge funds had an average return of only 36 percent net of fees over that ten-year period, while the S&P index fund had a return of 125 percent.

“You’re not trying to beat the market; you’re trying to stay with the market because over the long-term the market tends to go up.”

In the last twenty years, the rise of low-cost Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) have made it easy to invest in the broad market at a very low cost, and low cost is the key to long-term investing success because when you have to pay high fees it eats into long-term profits. Have a long-term plan to diversify your assets among stocks, bonds, and the home you own.

2. Stocks are the best long-term investment, but they don’t go up every year.

It’s a remarkable fact: since 1926, the overall stock market has been up three out of four years. The average increase in the stock market has been about 10 percent a year, including dividends. Over a very long period of time, research indicates that stocks are a better return than just about any other investment.

Stocks tend to go up because we live in a capitalist society. The U.S. has a particular brand of capitalism called market capitalism, where private individuals and corporations control most of the means of production. Market capitalism is an efficient allocator of capital—its primary concern is producing a profit—and it passes those profits on to shareholders. Other countries also have capitalist economies, but many—like many countries in Europe—have large parts of the economy controlled by the state. State-controlled enterprises are typically less profitable.

3. You may be able to take more risk than you realize.

I often hear people say, I can’t afford to have 75 percent of my retirement fund in stocks, I won’t be able to sleep at night. But even if you have 75 percent of your retirement fund in stocks, it doesn’t mean you have 75 percent of your assets in stocks. Think of your assets in three broad buckets: a retirement fund such as a 401(k), the home you own, and Social Security.

“Stocks tend to go up because we live in a capitalist society.”

Let’s say you have $250,000 in your retirement fund, your home is paid off and worth $250,000, and you collect $20,000 a year in Social Security, which is about the average per year. Over 25 years, a $20,000 a year Social Security check will be worth over $500,000. And remember, Social Security is an annuity that adjusts for inflation. So, $250,000 in a retirement portfolio, $250,000 in your house, and a half-million in Social Security receipts over 25 years, and you have a million-dollar portfolio, but only 25 percent of it is in a retirement fund with 75 percent stocks.

You don’t have 75 percent of your wealth in stocks, you only have about 18 percent in stocks. With that knowledge, you may feel more comfortable with a higher allocation to stocks.

4. Everyone is bad at predicting the future, and there’s a reason for that.

Amateur stock pickers are terrible at picking stocks, but professional stock pickers have a terrible record of picking stocks, too. Economists have a terrible record of predicting the economy. Even the Federal Reserve, with the best economists in the world, don’t have a good record of forecasting the U.S. economy. Why is everyone so bad at predicting the future?

There are two main problems. First, predictions riddled with bias limit the quality of those predictions. There are emotional biases from feelings like overconfidence after being right the last few times. There are cognitive errors that come from faulty reasoning because people often jump to conclusions based on limited information. They don’t question the quality of the information or what information might be missing. There is also confirmation bias in which people select information that supports their own point of view, while ignoring information that contradicts it. These biases and dozens of others make it difficult to predict accurately.

“Economists have a terrible record of predicting the economy.”

The other problem is a lack of complete information because unpredictable events occur that affect outcomes. Think about trying to predict the price of a stock one year from now. Every company has millions of variables which can affect the outcome. Some factors may be predictable, but many are not. The economy may face new shocks, such as inflation, a rise in interest rates, a war that disrupts critical supplies, or a cyberattack. The company may face a new competitor. It may be bought out or engage in an unforeseen merger. The visionary CEO may fall ill and suddenly retire.

5. Professional stock pickers aren’t bad at picking stocks because they’re stupid, they’re bad because the competition is tough.

When fees are taken into account, 90 percent of fund managers underperform their benchmarks after ten years. It’s not because they’re dumb—just the opposite. Decades ago, most trading was done by individuals with each other. Information was tougher to come by. Some were better informed than others.

But today, most trading is done by professionals like mutual funds and pension funds. All of these people have access to roughly the same information at the same time. They don’t have any informational or time advantages, which makes it very difficult for any one professional to outperform. Those that do usually don’t outperform consistently. Very few will ever put together a string of outperforming years.

To listen to the audio version read by author Bob Pisani, download the Next Big Idea App today: