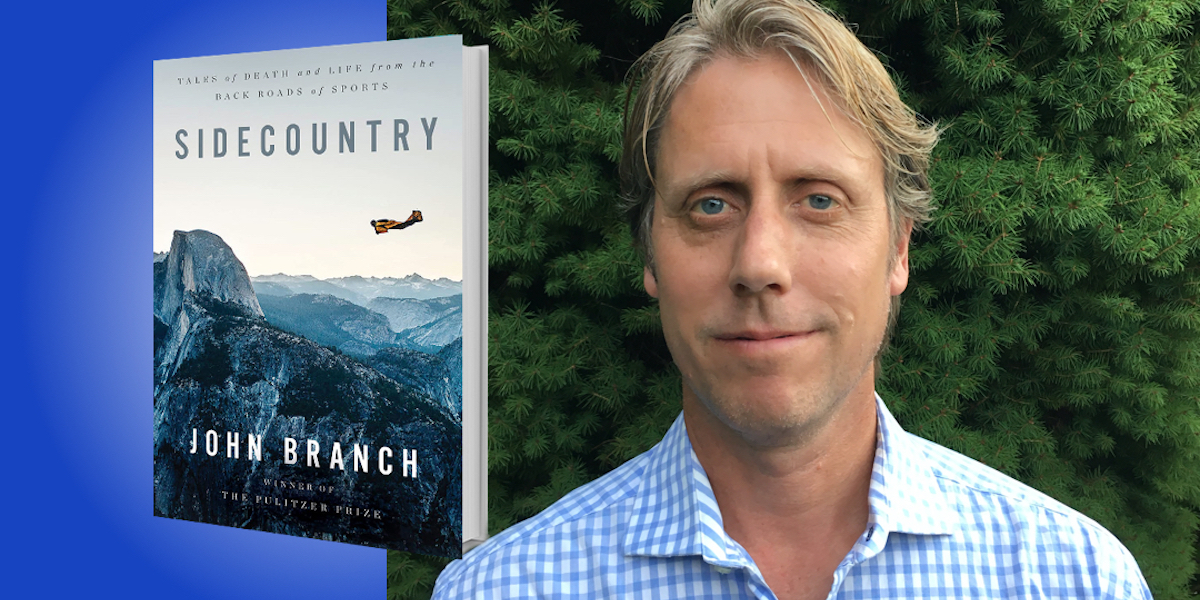

John Branch is a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the New York Times. He is the bestselling author of Boy on Ice and The Last Cowboys and has been featured multiple times in Best American Sports Writing.

Below, John shares 5 key insights from his new book, Sidecountry: Tales of Death and Life from the Back Roads of Sports (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by John himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Good journalists simply tell the truth.

What if all the stories we shared with one another were rooted in facts, firsthand observations, and trusted sources? What if someone simply told you what happened, without trying to spin the story or pass judgment on the people in it? In short, it’s my job to make you think, but not to tell you what to think. Who am I to say whether people should hunt alligators, ski in avalanche territory, or throw themselves off of cliffs while wearing a wingsuit and a parachute? I’ll introduce you to these people and tell the truth about who they are, and then you decide how to feel about it.

The stories in my book are all about real people, and they might open your eyes to different cultures, different viewpoints, and different places on the map. It’s okay if you know nothing about mountain climbing, big-game hunting, figure 8 car racing, or even solving a Rubik’s Cube in a matter of seconds. Yeah, kids do that—my son is one of them. And that’s the truth.

“It’s my job to make you think, but not to tell you what to think.”

2. Dare to be different.

I think there’s value in being different, perhaps now more than ever. We think we know what we like, so whether it’s news or sports, we’re always fed the same thing—and that’s what we consume. No one sells more hamburgers than McDonald’s, so McDonald’s keeps producing hamburgers—but no one thinks McDonald’s has the best hamburgers. So the question I always ask myself is, can I steer people toward somewhere unfamiliar? Can I get a reader to engage with a man from Ohio named Alan Francis, the most dominant athlete I’ve ever known? You’ve probably never heard of him, but he pitches horseshoes, has won more world championships than anyone, and throws ringers from 40 feet with the same rate of precision that Steph Curry shoots free throws from 15.

Or what about Max Park, an autistic teenager from California who solves Rubik’s Cubes faster than anyone in the world? And then there’s Don Doane, who was not the best at anything, and not known by anyone outside the small Michigan town where he grew up. But he loved nothing more than bowling on league night each week. In his early 60s, he finally bowled the first 300 game of his life—and moments later, he died of a heart attack. I’ve remembered that story more than anything I’ve written about anyone famous. My challenge as a journalist is to try to get others to feel the same way.

3. Find the unfamiliar in the familiar.

You probably remember the day that Kobe Bryant and eight others were killed in a helicopter crash. I went to Los Angeles to cover that crash, where I saw hordes of other reporters. Story after story was about Kobe Bryant, his daughter, the families of those who died, and all the fans who were crushed by the news. These were all worthy news stories, but so many reporters were working the same angles. I wasn’t sure what I could add to all of it.

“If we look hard enough, we can find unfamiliar meaning in familiar places.”

But a few days later, I saw people standing on the street, staring up at the crash site. They were looking for solace, for an explanation, maybe a hug. Their backs were to a little church, one of the closest buildings to the crash site. The crash actually happened on a Sunday, just as people were starting to arrive for services. Ah, there was my story—a quiet, simple, small church that woke up on another Sunday morning, only to have the biggest news in the world literally fall out of the sky across the street. It’s an example of how if we look hard enough, we can find unfamiliar meaning in familiar places.

4. Every good story is a human story.

In 2017, I was awakened in the night by editors who asked if I could get to Las Vegas as soon as possible. There had been a mass shooting a few hours before—dozens had been killed at a concert. I caught an early flight, landed, and received a text from my wife: A friend, the mother of a girl on my daughter’s soccer team, had been at the concert. And that night, her name was added to the list of more than 50 victims.

For a week, I covered the aftermath in Las Vegas, tracing the killer’s steps toward the high-rise suite at the Mandalay Bay. I left the human side of the story behind at home—that is, until I got back just in time for my daughter’s soccer game. I was surprised to see someone there: the little girl whose mother had been killed. She was the girl in the number eight jersey. And when she scored the winning goal, I broke down and wept. I wrote the story after the game, and it ran on the front page of the New York Times.

The point is that in any of these stories, you might learn something about avalanches, base jumping, or even a mass shooting. But those are just things—to connect with stories, well, that takes people.

“The truth is, everyone has a story—if we care enough to ask.”

5. Stories never really end.

We consume so many stories these days—not just books and newspaper stories, or even TV shows and movies, but podcasts and Instagram stories and Twitter threads. Stories are everywhere, and one thing they have in common is that they start, they have a middle, and they have an end. But when it comes to real life, stories don’t really end. Even when the story is about death, other lives continue.

Let me tell you about Ed Thomas, a revered football coach in Parkersburg, Iowa. One afternoon in June, the tornado siren sounded, and one of the biggest twisters in state history barreled through town. Ed and his wife hid in the basement, and when they came back up, their house was gone. Ed went to the high school and found that it, too, was destroyed. Half the town was scrubbed from the earth, and 12 people died. Ed did what he knew how to do; he decided that he would lead the cleanup of the high school, have the kids help bury the dead, and by God, there would be football come September. Sure enough, there was football—just as Ed Thomas promised.

I didn’t think there would be another story, but the next year I got a call. Ed Thomas was in the school’s temporary weight room on a summer morning when a former player walked in and shot and killed him. No one knows why. The boy’s parents were friends of the Thomas’s; they even went to the same church. One of the first things that Ed Thomas’s widowed wife did was call the family to say that she did not blame them. That was the third story—but afterwards, it’s not like all those lives in Parkersburg just stopped existing. A young man remains in prison. Ed Thomas’s wife lives alone. His son is now a football coach. Life goes on.

And this is where the reader, the consumer, you come in. Don’t let these stories end. Engage with them. Then pass them on. Learn from them. Follow up, and be curious. The truth is, everyone has a story—if we care enough to ask.

To listen to the audio version read by John Branch, download the Next Big Idea App today: