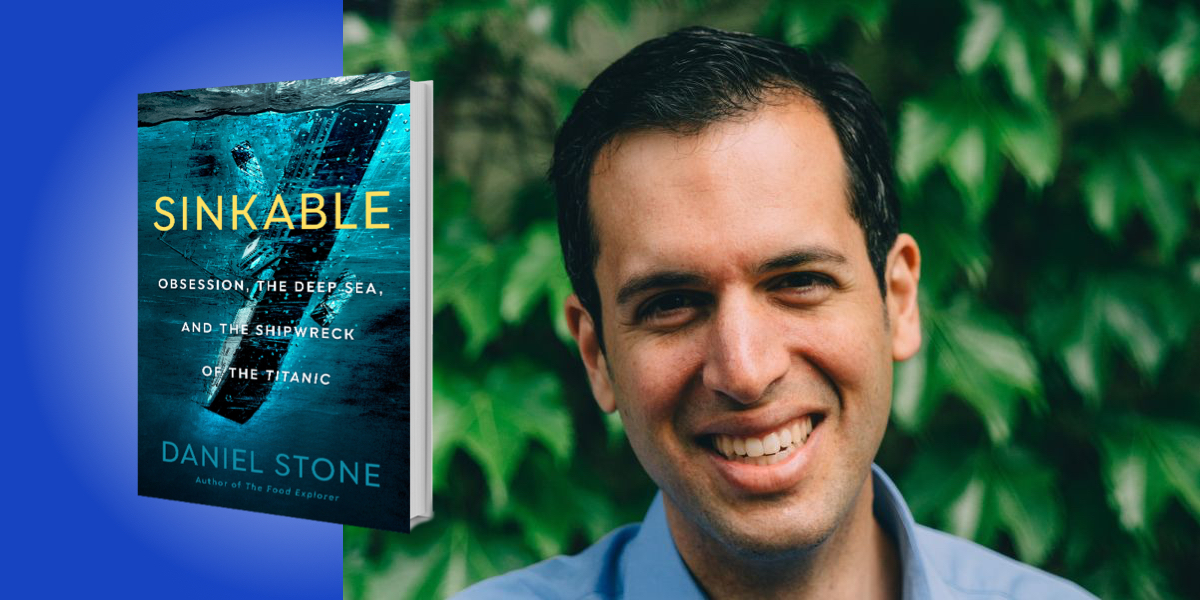

Daniel Stone is a national bestselling writer on science, history, and adventure. He’s a senior editor for National Geographic and a former White House Correspondent for Newsweek. He’s also a professor of environmental science at Johns Hopkins University.

Below, Daniel shares 5 key insights from his new book, Sinkable: Obsession, the Deep Sea, and the Shipwreck of the Titanic. Listen to the audio version—read by Daniel himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. There are far more shipwrecks than you think.

Every ship will eventually sink. Just like cars and airplanes, ships last between 20 and 50 years. And once they’re too old to run and too expensive or inefficient to operate, they most often end up at the bottom of oceans or lakes.

According to UNESCO, there are an astounding three million shipwrecks on Earth. And some archaeologists think that there could be as many as thirty million wrecks. There are wrecks in every ocean and every lake. There are wrecks in the deserts of Namibia and under cornfields in Kansas. When the twin towers fell on 9/11, excavators even found an old ship under the rubble. Almost anywhere on Earth, you’re never more than a few miles from a wreck.

2. It’s easier to map Mars than map wrecks on the sea floor.

Land-based maps are made by satellites that bounce micro-radio waves at the planet’s surface. But radio waves get stuck in water and don’t bounce back. So the only efficient way to map the bottom of the ocean is to map the surface of the ocean, which is never truly flat. Underwater gravity pulls and pushes water in strange ways. An undersea mountain five hundred feet tall will raise the sea surface above it about one foot. The seven-mile-deep Mariana Trench pulls water down more than three feet. In 2014, scientists discovered that undersea topography and swirling currents have the effect of sloping the ocean, and found that the sea level off the west coast of Europe is three inches lower than off the east coast of the United States.

3. “Women and children first” is a myth. Usually, they’re rescued last.

Women and children were given lifeboat priority on the Titanic—but this was an anomaly. In 2012, researchers studied eighteen maritime disasters involving 15,000 people of thirty nationalities over three centuries and found that men’s survival rates are twice as high as women’s. Children fare worst of all—just fifteen percent make it off sinking ships alive.

“There are still thousands of ships carrying as much as $60 billion in old gold, silver, diamonds, indigo, teak wood, and other valuables.”

What’s more, despite the notion of captains going down with the ship, the researchers found that captains and crew survive at significantly higher rates than passengers. “Women and children first” was a myth devised by British elites as an argument against women’s suffrage. Why do women need to vote, they argued, when even when facing death men will put women’s interests first? The age-old myth still persists.

4. The worst place to shipwreck is in the South Pacific.

If you’re on a sinking ship, it’s hard to convince yourself that it could be worse somewhere else. But there is a definitive worst place to have a shipping accident: Point Nemo in the South Pacific, between New Zealand and southern Chile. It’s the farthest spot on Earth from any major landmass—and that’s before its notorious rough seas and cold, polar temperatures. It’s also the unofficial dumping ground for aging satellites falling out of the sky. Wreck lovers don’t agree on much, but they do agree about Point Nemo: don’t go there.

5. Most sunken treasure is still at sea.

You might think that after decades of high-tech deep-sea exploration, all the good trophies are found. But there are still thousands of ships carrying as much as $60 billion in old gold, silver, diamonds, indigo, teak wood, and other valuables.

The most valuable one may be the Merchant Royal that sank near Cornwall, England in 1641. It is believed to be carrying $1.5 billion in gold. Other unfound wrecks are valuable because of their cultural value, such as Columbus’ Santa Maria, James Cook’s HMS Endeavour, or the SS Waratah, a deadly 1909 wreck often called Australia’s Titanic. It takes lots of money and high-tech equipment to look for wrecks, but people find them every day. Get yourself some deep-water engineers, some willing investors, and a boat, and you too can search for—and find—lost wrecks.

To listen to the audio version read by author Daniel Stone, download the Next Big Idea App today: