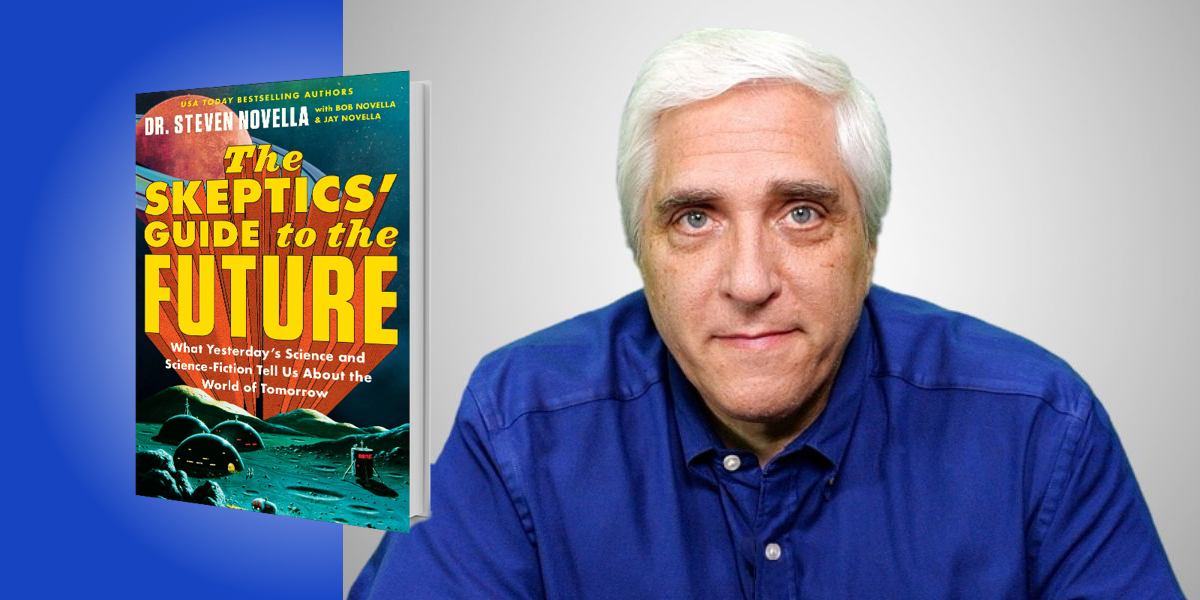

Steven Novella is an academic clinical neurologist at Yale University School of Medicine and is host and producer of “The Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe. Bob Novella is a co-host of the Skeptics’ Guide podcast and is founder and vice president of the New England Skeptical Society. Jay Novella is s a co-host of the Skeptics’ Guide podcast and serves on the board of directors for the Northeast Conference on Science and Skepticism.

Below, Steven, Jay, and Bob share 5 key insights from their new book, The Skeptics’ Guide to the Future: What Yesterday’s Science and Science Fiction Tell Us About the World of Tomorrow. Listen to the audio version—read by Steven, Jay, and Bob—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. There is now enough history of futurism that allows us to develop a list of common “futurism fallacies” that past futurists have committed.

Futurism has been around long enough—over a hundred years—that we can now look back at what past futurists said, and learn lessons from their successes and failures. The biggest mistakes that past futurists made are referred to as “futurism fallacies.” Learning from futurism fallacies, we avoid making those same mistakes while thinking about the future of technology.

Futurism fallacies come up over and over again, which is itself a lesson. The future is unbelievably hard to predict, and we are biased, inevitably, by our current culture. In the 1950s, when talking about the future, the “future” was people of the 1950s living in some supposed future. But the people of the ’50s would not be in that future. It’s going to be futuristic people living in that future.

There’s no attempt to pull the current culture out of the prediction of the future. It’s a knee-jerk reaction that futurists have and they can’t help it. The reason why you can’t help it is because it’s really hard to imagine what people are going to be like, and what they are going to think like. It’s also hard to guess what their reaction to technology is going to be. That’s almost impossible to predict.

We do, however, love to project ourselves into the future. When we talk about wanting a jet pack, a flying car, or an electric car, we’re putting ourselves in the position to be the recipients of that technology, even though, most likely, it will not be us who uses that technology.

“Things won’t change just to change.”

Another futurism fallacy predicts that future technologies will do away with all older, similar technologies. However, if you look at how technology is spread and developed, often you’ll have the older technology coexisting with the new technology. Older technology doesn’t go away, and often one finds an unanticipated niche that you never expected to find. Things won’t change just to change. When something works, even if it’s low-tech, it has a remarkable persistence into the future. You can trust that you will be cutting your vegetables with knives for centuries.

2. Just because something can happen doesn’t mean it will.

There are lots of reasons why a technology will not be become part of the future. Take the space elevator. People love the idea of the space elevator. Basically, you have a cable that you connect to the equator at one end, and to geostationary orbit at the other end. The elevators go up and down the cable as a means of getting into space, rather than launching rockets.

Once you have a space elevator, it becomes very cheap and convenient to get lots of stuff into space, and it could become an invaluable piece of infrastructure for a space-faring civilization. However, once you do a deep dive into the practicality of a space elevator, you realize that it’s probably never going to happen. The physics are pretty wonky and while it’s not impossible, space elevators exist on the edge of the probably impossible. We would need some major breakthroughs in materials technology to build a space elevator.

In another futurism fallacy, we imagine the future as a technological utopia or at the end of history where all conflict has resolved itself. We don’t consider that the future is going to be a real world with all the conflicts we have today. Would a space elevator be worth it? Would anyone invest that much into that piece of critical infrastructure when one bomb can take it out? Even imagining advanced materials, the structure itself would be considerably fragile.

It’s crucial to think of competing technologies. Even though we can do something, there may be an easier way to achieve it. So while imagining ideas like the space elevator, it’s important to do a thorough, holistic analysis and realize that most ideas will never come to fruition.

3. As technology advances, old distinctions will progressively blur.

Biology and machines are slowly merging. When you play out technologies into the future, they tend to meet in the middle. Biology becomes more mechanistic and machines become more biological. The biology becomes more digitized, such as with 3D printers. With a 3D printer, you take a digital image on your computer and turn it into a physical object. That’s digitizing the world. While extrapolating that technology out, you realize that down the line there will no longer be a difference between these things.

“The future will likely require us to change the very nature of the technology itself.”

When looking into the future, you may ask yourself whether we are going to be solving future problems with biological or machine approaches. The answer is likely both. Solutions will likely be in the middle of biology and machines The solutions maybe even be categorized into a third category. It won’t be biological or mechanical, it will be post-biological and post-mechanistic in ways that we can’t even imagine right now.

Similar would be the question of whether or not there will be a robot apocalypse in the future. Again, we’re thinking about current technology and then just making it more sophisticated and advanced. The future, though, will likely require us to change the very nature of the technology itself. In the end, the answer may very well be that robots and humans might merge with machines. Technology in the future might also just make the question itself obsolete. It’s easy to extrapolate the present. It’s much harder to come up with that change that nobody is seeing.

4. Science fiction writing can add incredible imagination to futurism, but it generally does a bad job at keeping the science accurate.

A lot of science fiction takes place in the future. Whenever a science fiction author has to imagine the future, they’re doing futurism, whether they realize it or not. So, how do science fiction writers do when they imagine the future? Generally, pretty bad.

To be fair, authors’ goals are not accuracy. They’re slaves to the narrative. While telling a story, sometimes science just gets in the way of a good story. Things like faster-than-light travel and artificial gravity have to be included in the story because you have to get your hero to the action fast. You can’t spend years traveling to your destination. We need to relate to the characters, even though they are sometimes hundreds or thousands of years into the future.

At a lot of science-fiction features main characters as human so the reader can relate to these characters. There are a lot of narrative devices and often, the needs of the story trump futurism. There also the practicality of using pseudo-science. Why do nearly all ships in science fiction have artificial gravity? Because the actors are on a stage or on set with gravity, and it just makes it a lot easier to pull a story together if it looks like actual life in present time.

“We suspend our disbelief all the time in order to receive what we consider to be good and fun science fiction.”

We also need to tell a story that makes sense and has good pacing. We can’t have it be so unbelievably different than what people are used to seeing, or else the story doesn’t function anymore. In the end, that’s okay. We suspend our disbelief all the time in order to receive what we consider to be good and fun science fiction. As a consumer, we have to be okay with it.

5. While we can extrapolate technology, we can’t know the billions of decisions that will actually shape our future.

You can’t predict the future. So, what we try to do instead is extrapolate possible pathways for technology into the future. With the limits of physics, a gravity generator is not going to happen, and we’re probably not going to go faster than light. You can be very confident saying we’re not going to have these things in the future. Instead of saying “In the year 29,000 we are going to have….” you can say “What is possible or probable is….”

The speed of light is impossible for people to travel, and interstellar travel’s never going to be easy and convenient. When talking about certain specific technologies or maybe how different technologies interact in the future, it’s important to talk about how multiple technologies are going to interact with each other, rather than predicting the role of one single technology in isolation.

We also have to consider a range of possibilities when imagining our future. Our future will probably end up somewhere in between the best and worst case scenario. A lot of the technology, if you think about it, lands us in the middle of best and worst case scenarios. Consider nuclear technology, which allows for nuclear power and nuclear bombs from the same technology. The same thing occurs with other technologies. We could have robots that could make our lives easier, but they could take over the world. Nanotechnology could revolutionize manufacturing or swallow up everything in a great goo.

The future is ultimately made of the choices that we make today. All eight billion people on this planet have an effect on others. It’s the cumulative effect of all these decisions and not only the decisions from today; it’s everyone’s tomorrow and the next day and the next year and the next decade. All of those decisions, between now and whatever future you’re imagining, will create that future. You can’t predict the future, because it’s not inevitable. It is created by us, by the decisions that we make.

To listen to the audio version read by co-authors Steven, Jay, and Bob Novella download the Next Big Idea App today: