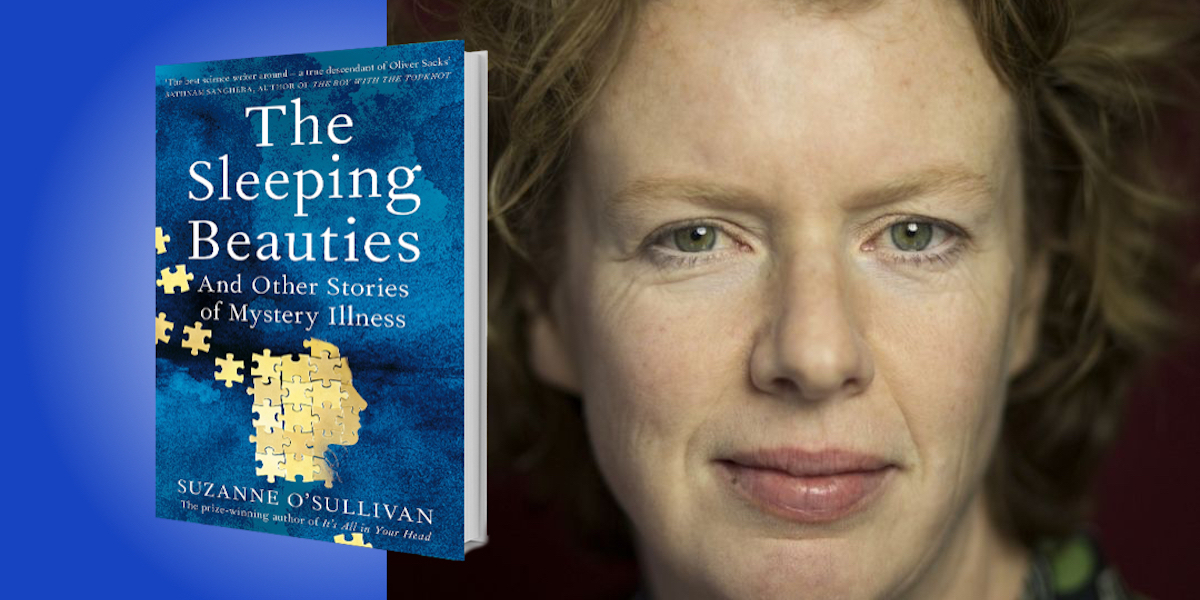

Suzanne O’Sullivan is an Irish neurologist working in Britain. Her first book, Is It All in Your Head?: True Stories of Imaginary Illness, won the 2016 Wellcome Book Prize and the Royal Society of Biology General Book Prize.

Below, Suzanne shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Sleeping Beauties: And Other Stories of Mystery Illness. Listen to the audio version—read by Suzanne herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Are we prejudiced in the way we judge disability?

Since the early 2000s, hundreds of asylum-seeking children in Sweden, some as young as seven, have fallen into a psychologically mediated coma. For months or even years at a time, these children do not eat or speak or move. In 2018, I met some of them: Tiny girls carried around by their parents like rag dolls; teenagers growing from childhood to adulthood in their beds. Their medical disorder, referred to as “resignation syndrome,” is generally accepted to be the product of psychological trauma and lost hope. Shockingly, most of these children lie at home in receipt of no active medical care. Their parents keep them alive with tube feeding and amateur physiotherapy.

Resignation syndrome provides a stark example of society’s attitude to psychosomatic suffering. If these children had a brain disease, they’d likely be in hospital—but psychologically and socially driven illnesses are easy to ignore. Some may wonder if the lack of action for these children is more about their refugee status. In part certainly yes, but in a larger part I would say no. I have seen psychosomatic suffering subjected to an apathetic response and a downgrading of sympathy in every society.

Imagine two people who can’t walk—one due to a spinal injury, the other for psychological reasons. Even when they are equally disabled, equally unable to walk, it’s common for the person with the psychologically mediated disability to be treated less urgently and with less respect than the other. Indeed, there are many groups fighting against psychosomatic diagnoses, as accepting them comes with a real risk of public ridicule and neglect.

“If these children had a brain disease, they’d likely be in hospital—but psychologically and socially driven illnesses are easy to ignore.”

2. Are we really in control of our bodies?

In 2016, a U.S. diplomat in Cuba heard a loud noise and almost immediately suffered an array of symptoms including hearing impairment, loss of balance, and difficulty concentrating. Thus began a rumor that U.S. diplomats were under attack by a sonic weapon. What followed was an outbreak of people with similar symptoms, first in Cuba, and now in embassies all over the world. Citing the fact that a sonic weapon has never been known to exist and the inconvenient truth that sound does not damage the brain, many experts believe these diplomats are caught in mass hysteria. Opponents to this suggestion argue that previously healthy, intelligent people don’t lose control of their bodies without disease. I hope to convince you that they do—and it’s not even unusual.

The healthy body is not within conscious awareness most of the time. We walk and sit and scratch our heads without planning or thought. A person doesn’t think about how their body feels or how movements happen—they simply happen. Experience allows us to negotiate our way through the world on autopilot. But what is the effect of bringing those unconscious processes to our attention?

Imagine I asked you to walk a heel-to-toe straight line in the middle of a basketball court. Most healthy people would do that without difficulty. But now imagine I asked you to walk the exact same line, but at the top of a wide but very high wall. The added jeopardy forces a person to pay more attention to their movements, which in turn changes the quality of the movement, making it less fluid and less reliable. Thus, with nothing more than a change in circumstance, a healthy person could struggle to keep their balance.

Now imagine I ask you to pay intense attention to all the sensations in your left hand. Do you notice tingling that didn’t appear to be there before? Our bodies are awash with white noise, which our brains dismiss when we are healthy, but which is available to be noticed if we are given reason to notice. That tingling was always there.

“Psychosomatic symptoms do not come from nowhere. They come from the fragility of unconscious cognitive mechanisms.”

In 2017, after the sonic weapon rumors started, authorities at the highest level instructed US diplomats to search their bodies for signs of an attack. They were told to hide behind walls if they heard any strange noises. Even those who were well were asked to go to the doctor to be examined. How did that change those diplomats’ relationships with their bodies? Did it derail the unconscious motor controls, and literally force them to pluck bodily sensations out of the white noise?

Psychosomatic symptoms do not come from nowhere. They come from the fragility of unconscious cognitive mechanisms. They appear because we are not as in control of our bodies as we think we are.

3. Hysteria is a feminist issue, but not in the way you think.

Many believe that the “hysteria” label is used to dismiss women’s suffering, but I suggest it is a medical disorder that is dismissed because women are its preferred victims.

In upstate New York in 2011, a group of high school students developed contagious tic-like movements and seizures. This began in a single friendship group before spreading to others in the school. In Colombia in 2014, in a similar epidemic, seizures wrought havoc among schoolgirls in a small town. That outbreak is still ongoing. In each of these cases, the vast majority of those affected were teenage girls.

It’s fascinating to observe the difference between the way these young women were treated when compared with the U.S. diplomats in Cuba. The media referred to the New York school girls as “fragile.” News programs detailed which of them came from single-parent families. Their personal stresses, parental discord, hardships, and poverty were picked over. One news headline referred to them as “witches.” In Colombia, meanwhile, the teenage girls were told they needed husbands—that they needed more sex, or less. People said the history of violence in Colombia had made its way into psyches.

“When women are suspected to have psychosomatic illness, they are treated to the most outdated and pejorative versions of how that disorder is understood, while men avoid those judgments.”

And what was said about those U.S. diplomats? Nothing was said of their personal lives—nothing at all. The diplomats were older and privileged, and a reasonable proportion of them were men. Nobody asked if they were divorced, or if they came from broken families. Nobody cared about the state of their relationships or their sex lives.

When women are suspected to have psychosomatic illness, they are treated to the most outdated and pejorative versions of how that disorder is understood, while men avoid those judgments. Hysteria says a lot about how differently men and women are viewed by society, and maybe we should learn from it.

4. “Psychosomatic” does not mean “stress-induced.”

A hundred years ago, Freud attributed all hysteria, as psychosomatic symptoms were once known, to psychological conflict. He believed that a symptom would dissipate if it could be traced back to the moment of psychic trauma that caused it. Although a century old, this idea is still prevalent, yet lots of people with these medical problems say they are not unduly stressed. So are they in denial? No, they are not. Psychological distress, anxiety, unhappiness, and fear do take a physical toll, but that’s far from the whole picture.

Tara is a patient of mine, and her problem began when she pulled a muscle in her back. A previously well schoolteacher, she was suddenly in a lot of pain. A scan showed a minor disc displacement in her spine, which her doctors dismissed, but which worried Tara. The pain and the knowledge that she had a slipped disc forced Tara to examine her back and legs for signs of deterioration. She noticed the aforementioned white noise, which made her legs feel strange, which then disrupted the automatic quality of movement. As she changed her gait to accommodate her pain—as she became unnaturally focused on her legs—she slowly unlearned a previously unconscious process. Within six months, she struggled to walk.

Now, in a traditional Freudian model of hysteria, a doctor would be expected to search Tara’s life for some hidden stress—but it never existed. Tara’s was a maladaptive response to injury. Through a cycle of attention, fear, and avoidance, she had unlearned walking. She didn’t need a psychologist to unpack her childhood or probe into her personal life. She needed a physiotherapist to help her regain confidence in her body, to train her back to walking in much the same way that an athlete is rehabilitated after an injury. So while psychological stress causes psychosomatic symptoms, it is far from the only cause.

“Perhaps we should be listening more carefully to the story the symptoms are trying to tell, and follow them to the solution.”

5. Sometimes psychosomatic disorders are necessary.

Between 2012 and 2016, 133 people in Krasnogorsk, Kazakhstan fell into a mysterious sleep. Extensive medical and environmental testing ruled out disease. Many believed this outbreak had a psychosomatic cause and, as such, attributed it to stress. But the people affected did not accept that explanation—they believed they had been poisoned. I would suggest that their illness was neither stress-induced nor poison-related, but rather it was a complex and almost beautiful solution to a social problem.

Krasnogorsk was once a unique and special place. In the Soviet era, it was paradise—a uranium mining town, it was under protection from Moscow. Unlike the rest of Kazakhstan, its people lived in luxury. Shops were well-stocked. It had modern apartment blocks, a cinema, crèches, and a first-class hospital. But when the Soviet Union collapsed, the town lost its special status, and the luxuries disappeared.

But it wasn’t the death of the town that made the people sick. It wasn’t hardship—they weathered that for 20 years before they began to fall into an apparently inexplicable coma. That, I suggest, was actually caused by love. Living with dwindling amenities, people struggled to accept that Krasnogorsk would never get back to how it was, and that they would have to move on. They loved their town, and the sleeping sickness was part of a sophisticated solution that gave them permission to leave it.

Life is full of difficult decisions and personal problems that are too hard to talk about, and that defy ordinary lists of pros and cons. It may be that psychosomatic symptoms are part of a process that help us solve such problems. They allow us to take a break. They alert others to our need for help. They give us permission to make a change. And, if there are times when psychosomatic symptoms have come to provide an indirect solution to an unconscionable dilemma, perhaps biologizing and psychologizing are not the answer. Perhaps we should be listening more carefully to the story the symptoms are trying to tell, and follow them to the solution.

To listen to the audio version read by Suzanne O’Sullivan, download the Next Big Idea App today: