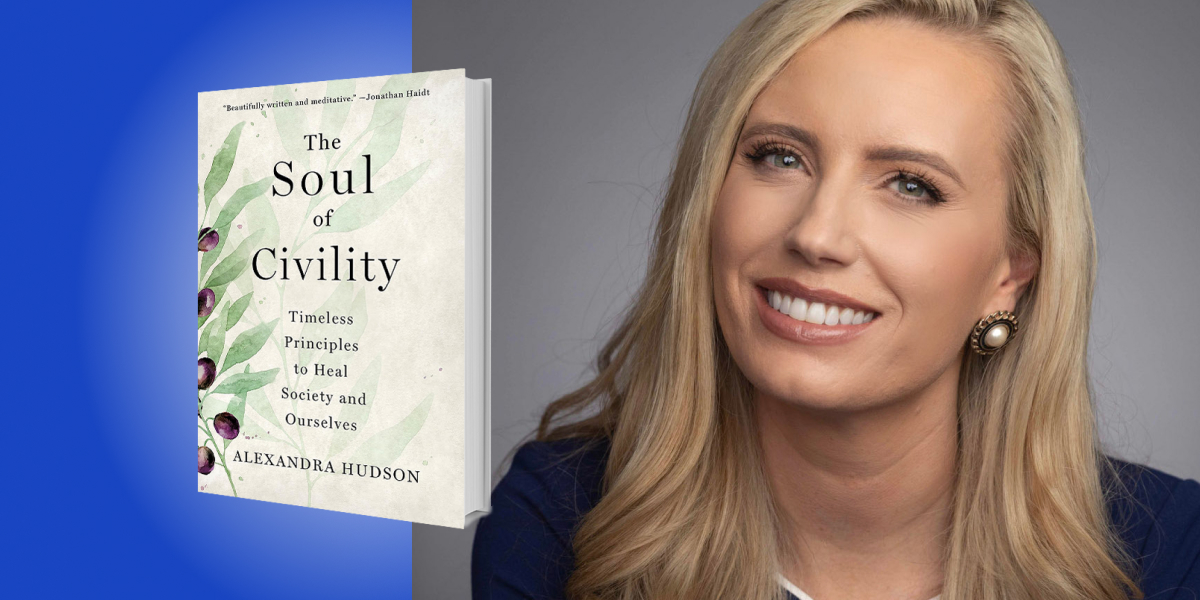

Alexandra Hudson is a writer, popular speaker, and the founder of Civic Renaissance, a publication and intellectual community dedicated to beauty, goodness, and truth. She was named the 2020 Novak Journalism Fellow and contributes to Fox News, CBS News, The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, TIME Magazine, POLITICO Magazine, and Newsweek. She earned a master’s degree in public policy at the London School of Economics as a Rotary Scholar, and is an adjunct professor at the Indiana University Lilly School of Philanthropy.

Below, Alexandra shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Soul of Civility: Timeless Principles to Heal Society and Ourselves. Listen to the audio version—read by Alexandra herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Why the oldest book in the world is about civility.

It’s appropriate for a book club to look at insights from the world’s oldest book! We are currently confronting the question of how to do life together across difference—which is the most important question of our day. But it is not a new challenge. It’s actually timeless. The human condition is defined by two competing forces: our love of others, and our love of self. We are an insatiably sociable species. We yearn to be in community together, yet our self-love always threatens the human-social enterprise, which is why friendship and community will always be fragile. That the oldest book in the world is about how to flourish despite difference shows how seriously our species has thought about this central question.

Two thousand and four hundred years before Christ, there lived a wealthy and powerful statesman named Ptahhotep. Ptahhotep was an advisor to Pharaoh, the leader of Ancient Egypt, the time’s most sophisticated civilization in the world. He had made it to the pinnacle of earthly success. He had been in the room where big, world-altering decisions were made. He had helped shape the direction of the world’s most advanced society. He had tasted the best and finest things that money and power could buy. Ptahhotep was set to succeed Pharaoh as ruler of Egypt, but he turned down the offer of temporal power to live a quiet and honorable life in retirement. After his withdrawal from an illustrious public life, he began to reflect on the ingredients of the life well-lived.

He resolved to write a letter about his life lessons to Pharaoh’s son in hopes that he might take the lessons to heart, and lead Egypt with wisdom and grace. His maxims are what is considered today the oldest book in the world—and his teachings are remarkably relevant to today. “Do not be proud and arrogant with your knowledge,” the Teachings begin. “Wretched is he who injures a poor man.” Teaching Eight instructs, “Do not malign anyone, great or small,” and Teaching Twenty-Two, “Don’t repeat slander nor should you even listen to it.” The Teachings of Ptahhotep wrestles with this universal problem: how can we overcome our selfish natures so that we can live with others?

Ptahhotep offers us an answer: Civility.

2. There is an essential difference between civility and politeness.

Part of my story is that I was raised by Judy “The Manners Lady” and then was disillusioned by my experience working in politics in Washington D.C. I quickly learned that those who survived and succeeded in Washington did so because of their punishing ruthlessness or extreme politesse. At first, I thought these two modes were opposite extremes of the same spectrum.

Instead, they were actually two sides of the same coin. They were both modes that originated from a dark place in the human spirit—a place where we are willing to instrumentalize others, and do whatever is necessary to win.

“Civility gets to the motivation of an act.”

Some people—usually the younger, greener politicos—chose to be overly aggressive and hostile. The more seasoned political operators, however, were shrewd. They knew that overt aggression would only take them so far. They instead chose politeness as the weapon of choice. This allowed them to shroud their opportunism in the appearance of altruism while disarming their opponents, disguising their true aims.

My mother had always told me growing up that manners were an outward expression of our inner character. Yet, I was surrounded by people who were well-mannered, but ruthless and cruel.

This experience helped me realize that civility and politeness were different things. People tend to use “civility” and “politeness” interchangeably when referring to manners, etiquette, and social norms. But not all social norms are equal—or desirable.

While politeness and manners are the form, the technique of an act, civility is deeper. Instead of focusing on the form alone, civility gets to the motivation of an act. Instead of the technique of politeness, civility is a disposition that recognizes and respects the common humanity, the fundamental personhood, and the inherent dignity of other human beings. Civility sometimes requires that we are impolite to others, in telling them hard truths or engaging in robust debate. These modes may seem rude—but are in fact ways to truly respect others.

3. We must begin “unbundling” people.

Too often today, we reduce people to one aspect of who they are. We define them by their worst trait or decision—something they said or did, which they probably regret, but which, thanks to the internet and social media, has been immortalized and widely circulated. Instead, we should “unbundle” them. Unbundling is a mental framework that helps us see the part in light of the whole—the bad of a person in light of the good.

Our current culture views the world and people through a cheapened simplicity. Everything, and everyone, is either right or wrong, good or evil. We define people based on one thing they’ve done or said, sometimes even if it occurred years or decades ago, and “cancel” them for it. This view of the world and people is reductive, essentializing, and degrading to the diversity and beauty of the human personality.

“Socrates said that virtue is health of the soul, and vice is sickness of the soul.”

I’ve had practice unbundling in my own life. I’ve had to grapple with balancing the good and the bad of such as Socrates. Socrates enchanted me with the rewards of the philosophic life, the world of ideas, the life of the mind, and the nobility of a life of embodied beauty, goodness, and truth. Socrates said that virtue is health of the soul, and vice is sickness of the soul. Virtue is its own reward, he said, because it promotes a healthy soul. Vice is its own punishment, because it reflects a soul’s ill health. A life detached from the temptations of the world, Socrates said, allows us to more freely pursue the philosophic life—the highest and best life. These ideas captivated my mind and enlarged my soul.

And yet, as his student Plato describes him, Socrates was a proponent of eugenics. Socrates wanted to abolish the family, art, poetry, and music. As a humanist, mother, and artist, I vehemently disagree with these ideas. Do Socrates’ bad opinions on eugenics or banning the family or art in society undermine his thoughts on why virtue is good for its own sake, or on the rewards of the philosophic life? Absolutely not.

“Unbundling” people can help us reclaim a full, nuanced, and rich view of the human person. It can help us see the part in light of the whole, mistakes in light of virtues. It can help us see our selfish, domineering nature in light of our dignity as human beings, and our irreducible worth as persons.

4. Incivility—disrespect for others—hurts others, but also hurts oneself.

The title of my book is The Soul of Civility. The “soul” reference pays homage to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s letter from a Birmingham jail. King taught me that there is a moral foundation for civility. Treating others with decency, dignity, and respect is nonnegotiable because they are our fellow human beings.

As King said, human beings share an irreducible, equal moral worth. We have dignity, Dr. King noted, which is why he dedicated his life to creating a world “in which all men will respect the dignity and worth of human personality.” Human dignity was the moral bedrock of his battle against racism. It is also the moral foundation for civility.

“Human dignity was the moral bedrock of his battle against racism.”

King wrote that segregation hurts both parties involved. It degrades the dignity of the segregated because it gives them a false sense of inferiority. It deforms the soul of the segregator because it gives them a false sense of superiority. The same is true for civility. It’s often said that nice guys finish last. How can they compete with someone who is willing to do or say anything in order to win? But the truth is when someone is malicious to others in order to “get ahead,” they don’t actually win at all. They debase themselves, as they do the person to whom they are cruel. Just as civility ennobles both parties, incivility hurts others and the self.

5. How the “Porching Revolution” can change the world.

In an attempt to flee the divided nature of Washington politics, my husband and I moved back to his home state of Indiana. Soon after, I received an unexpected invitation after church one day. “I’m Joanna Taft,” said the tall, socially fearless woman with a blond bobbed haircut cut and a ready smile. “Would you like to porch with us sometime?” she asked. This marked the first time I had heard the word “porch” used as a verb.

For Joanna, porching is about reviving the community living room. The porch is a quasi-public “third place,” a neutral ground where people from different backgrounds can encounter and befriend one another.

Though originally from the Washington D.C. area, Joanna chose to build a life in Indianapolis with her husband and family. She has cultivated her porch as a haven from the hurriedness of modern life. It is a place to forge new friendships, an incubator of ideas to make the community brighter, a catalyst for further cultural and communal growth, and a venue where those who differ politically, racially, and culturally can form bonds and feel seen, known, and loved. I realized that the civility of Joanna’s front porch was the essential building block of civil society—and in turn our democracy.

Joanna is staging a revolution against our atomized and fractured world, all from her front porch—what I call the Porching Revolution, and we can, too. Anyone, with or without a porch, can be part of this subversive rebellion to heal their family life, their community, and even the world one relationship, and one interaction—one act of civility— at a time.

To listen to the audio version read by author Alexandra Hudson, download the Next Big Idea App today: