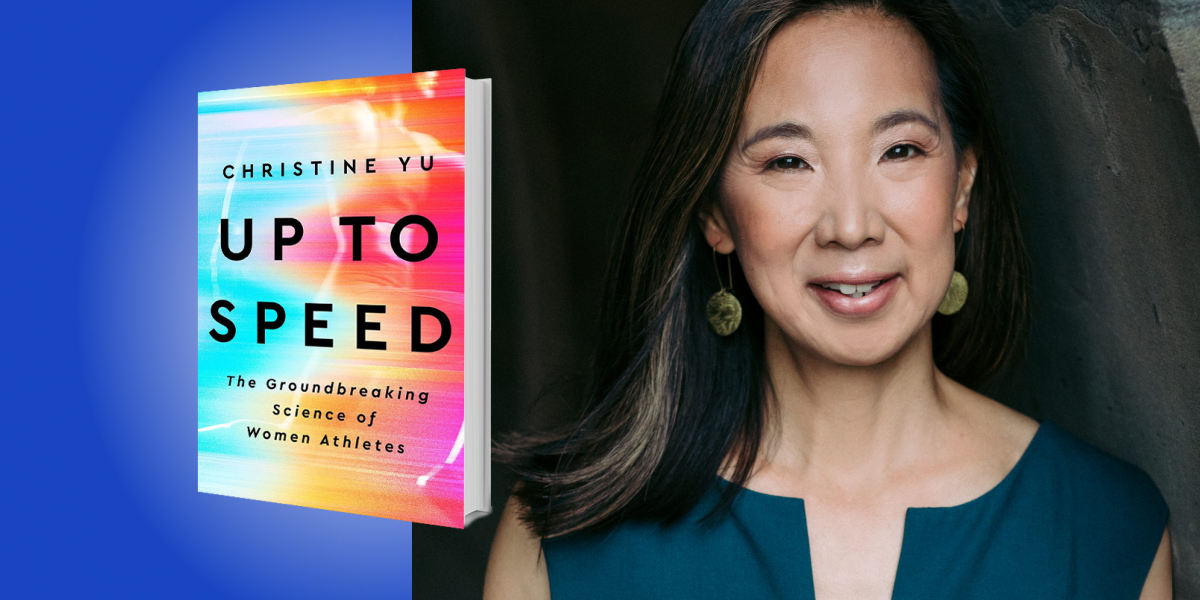

Christine Yu is an award-winning journalist whose work focuses on the intersection of sports science and women athletes. Her writing has appeared in Outside, The Washington Post, Runner’s World, and other publications. She’s a lifelong athlete and yoga teacher who loves running, surfing, and skiing.

Below, Christine shares 5 key insights from her new book, Up to Speed: The Groundbreaking Science of Women Athletes. Listen to the audio version—read by Christine herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. What we know about exercise and sports is based on studies of men.

Throughout history, women have been kept off the pitch, the court, and the starting line, and they’ve also been kept out of the research labs. So much of what we take as gospel about exercise and sports is based solely on studies of men.

For decades, scientists have worked under the assumption that women and men are biologically and physiologically the same if you ignore the reproductive organs. But as I read more papers and talked to more experts, I realized that the exclusion of women was more than an oversight.

Over the last fifty years, the number of girls and women participating in physical activity and sports has grown tremendously at all levels, but the field of sports science hasn’t kept up with this rising population of active women. Between 2014 and 2020, only 6 percent of sports science research focused on women, and women made up just 34 percent of study participants.

That means our understanding of sports science is weighted heavily towards men and male bodies. This can distort our understanding of what’s considered “normal” physiology. Men’s experiences set the standards for athletic progression, training, nutrition guidelines, injury prevention protocols, and athletic gear design. We end up making assumptions about exercise and fitness based on a partial picture of the human population.

The omission of women creates a blind spot that allows society and institutions to routinely brush aside women’s concerns and position them as an exception to the rule rather than part of the norm.

2. If we want sports to be more inclusive, science needs to be more inclusive.

When you don’t see yourself in the research literature or it doesn’t reflect your lived experience, you’re left without appropriate or adequate guidance. It makes you question your place in sports and who physical activity is for.

Practically, this means girls and women don’t have access to the same level of training and nutrition guidelines, injury prevention protocols, and even clothing and gear as boys and men. Even in the 21st century, coaches, doctors, athletic trainers, and athletes themselves know the bare minimum about women’s health and their struggle to find care and advice.

“Practically, this means girls and women don’t have access to the same level of training and nutrition guidelines, injury prevention protocols, and even clothing and gear as boys and men.”

Take the sports bra, for example. The sports bra wasn’t invented until 1977—less than 50 years ago. It was the height of the jogging boom and there wasn’t a good solution to control breast movement while running. Three women in Vermont—Lisa Lindahl, Polly Smith, and Hinda Miller—ended up sewing two jockstraps together, which eventually became the Jogbra.

The sports bra is a necessary piece of equipment for active people with breasts, and breast pain is a major barrier to physical activity and sports. But sports bras haven’t always been given their due respect. They’re written off as just a piece of spandex, without recognizing their immense and multifaceted job. Breasts weren’t deemed worthy of investigation by bra designers and biomechanics researchers, who were mostly men. But without studying breast motion, there’s no way to design a garment that effectively controls that motion.

It wasn’t until the late 2000s and 2010s that researchers, primarily women, got the technology that allowed them to study breast movement in a meaningful way. They are now using that information to design better, more comfortable garments that meet the needs of a diverse range of bodies. The sports bra is just one example of how a decidedly “female” issue has been overlooked because it doesn’t fit into the male-centric concerns that science and sport deem as important.

3. It’s the system.

I will admit, as a non-scientist, I would often skip the methodology section in research papers. Why did I need to know how they set up an experiment if I wasn’t planning on replicating it? I wanted to get to the good stuff—the results and the discussion. But I soon realized that methodology matters a lot. Methodology creates the parameters through which we understand the research findings and underlying assumptions that perpetuate a specific point of view.

One of the most prominent research laboratories to study human physiology and exercise was the Harvard Fatigue Laboratory. When the lab was established in 1927, its mandate was to understand the causes of fatigue so that companies could get the most out of their factory workers. To study fatigue, they wanted to investigate how the body adapts to stress and maintains a “steady state.” Their ideal study participant became athletes who (especially in those days) were predominantly men.

“Methodology creates the parameters through which we understand the research findings and underlying assumptions that perpetuate a specific point of view.”

The lab set the bar for exercise physiology research and its founders are considered the “forefathers of sports science.” When the lab closed 20 years later, its staff and former students—all men—dispersed and established 17 laboratories across the United States, bringing the methodologies of their mentors with them and teaching a new generation of scientists. It’s no wonder that women have continued to be left out of the scientific research because they weren’t considered in the first place as part of the standard methodology. For instance, of the 94 percent of sports science studies between 2014 and 2020 that focused on men, only 0.6 percent of those studies investigated a topic unique to men. In other words, women could have been included in the remaining 99.4 percent of studies but weren’t.

I don’t believe that any one scientist or research group intentionally neglected to consider women in their studies. There wasn’t a precedent to include women because of the way the system was established. They weren’t even aware that women were missing.

4. There’s no expiration date on women’s active lives.

Myths about women’s bodies and what they can do have persisted since antiquity. It was believed that features such as a uterus, ovaries, breasts, and menstrual cycle made women inherently incapable of engaging in the same pursuits as men. Physical activity was thought to harm a woman’s reproductive capacity, so she needed to be protected. That’s why women weren’t allowed to compete in the ancient Olympic Games, why women were advised to walk around their house and yell at their servants for exercise during the Renaissance, and why women weren’t allowed to participate in the ski jump until the 2014 Olympics. (They thought the impact of landing would cause the uterus to burst.)

Even as more women have taken up physical activity and sports, girls and women are still told that their bodies aren’t fit for sports. For instance, puberty is assumed to impair sports performance in girls because their athletic development doesn’t continue in a stepwise pattern like it does in boys. Instead, their progression stalls as girls grow into and adapt to their widening hips, growing breasts, and fluctuating hormones. But instead of recognizing that these changes are a normal part of the maturation process, girls are blamed and shamed for their maturing bodies and the dip in athletic progression. Similarly, during the menopause transition, a woman’s fitness can feel like it falls off a cliff. The body doesn’t respond to training the same way it did in her 20s or 30s and somehow, it’s made to feel like a woman’s fault.

But the problem isn’t women’s bodies. It’s that the typical model of athlete development and sports performance doesn’t accommodate women’s experience. Women go through multiple transitions—puberty, adulthood, pregnancy, and menopause—and these transitions affect the body in ways that men don’t experience.

“The typical model of athlete development and sports performance doesn’t accommodate women’s experience.”

When women are given the support they need to navigate these transitions, they can thrive. For instance, there’s a baby boom among elite runners right now. Previously, athletes would put off starting a family until the end of their career. It was in large part because sponsors wouldn’t pay athletes if they weren’t racing, even if they were pregnant or postpartum. Women were also left without evidence-based guidance to help them return to high-level exercise and competition. When your body is your career, it wasn’t a risk many wanted to take. If an athlete did get pregnant, there was immense pressure to return-to-sport quickly, which could lead to long-term injury or other health problems.

Now, more sponsors are supporting their athletes, not only financially but by giving them time to safely resume training. Organizations like &Mother are providing childcare and lactation support at major races that provide athlete mothers with resources to continue their career and care for their family. We’re also learning more about what women need to recover from childbirth and return to sport. By rethinking these life stages, we can support women’s lifelong active and athletic goals.

5. The secret to sports performance is “me-search.”

Scientific research offers a starting point for what might be happening in the body and can provide important details to inform training, fueling, injury prevention, return to sports, and staying active throughout life. But research studies often report on group response or the average effect across all participants. To make sense of this information and determine if it is applicable to you, requires a lot of trial and error.

Humans are wonderfully diverse and messy beings. We aren’t just a collection of hormones, bones, and muscles or an amalgamation of data points in a perfectly controlled laboratory setting. We need to consider the full context of a person’s lived experience to identify the best path to achieve one’s athletic goals.

To listen to the audio version read by author Christine Yu, download the Next Big Idea App today: