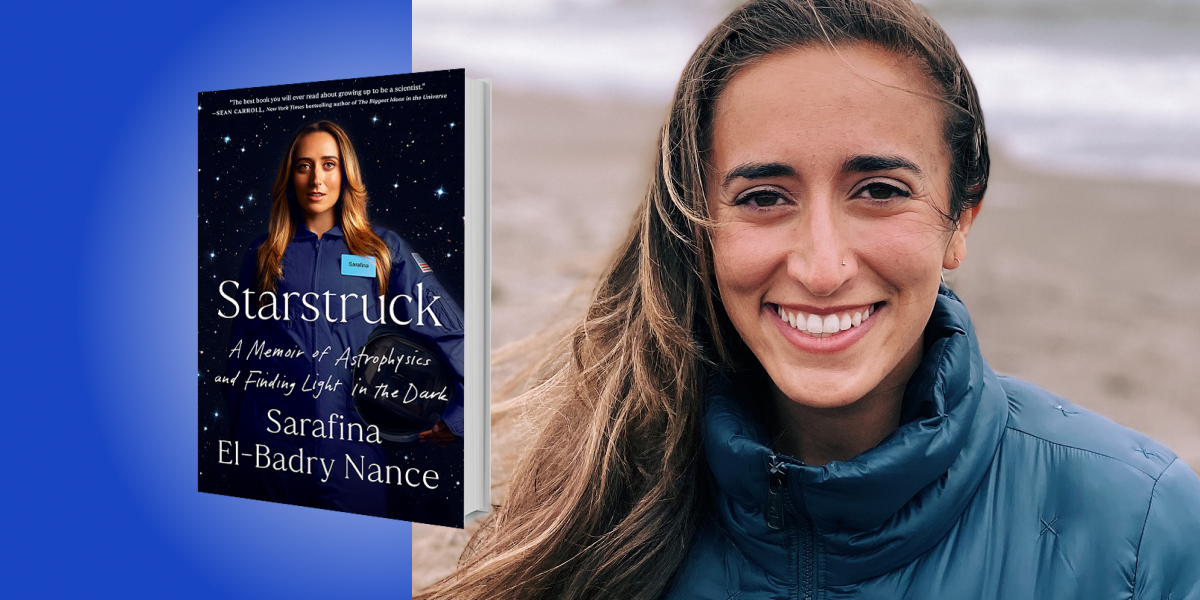

Sarafina El-Badry Nance is an astrophysicist specializing in supernovae, and an analog astronaut, having participated in Mars simulations. She is a National Science Foundation graduate research fellow at the University of California, Berkeley. She is also a fervent women’s health advocate, currently serving as a board member for Operation Period, a youth-led nonprofit dedicated to menstrual freedom.

Below, Sarafina shares 5 key insights from her new book, Starstruck: A Memoir of Astrophysics and Finding Light in the Dark. Listen to the audio version—read by Sarafina herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Find your night sky.

I’ve always been obsessed with space. During car rides to school, I would listen to NPR’s StarDate Radio. At night, I star-gazed with my dad. As someone who has struggled with anxiety for as long as I can remember, the enormity and endless wonder of the night sky provides me with a much-needed sense of perspective. It reminds me how small our daily struggles are in the grand expanse of the universe, while reinforcing a sense of connection—with the universe, with each other, and within ourselves.

Despite my love for the cosmos, for most of my life I didn’t believe that science was possible for someone like me. I felt out of place in the halls of science and was repeatedly told, both explicitly and implicitly, that I don’t belong: as a woman, as an Egyptian-American, as a student to whom physics or math didn’t come particularly easily.

Yet my love for the night sky served as my reprieve. As I carved out a place for myself in the world, ultimately becoming an astrophysicist, that passion and curiosity has been my ballast. It has kept me grounded so that I have the courage to explore the universe.

2. Curiosity is an act of resistance.

During the summer of my fifth-grade year, I went to science camp in the Texas Hill Country where, for the first time in my life, I met a professional astronomer. What should have been a thrilling meeting (he had my dream job) ended up as one of my most formative, defeating moments. When I confessed that I wanted to be an astronomer too, he replied that astronomy “wasn’t for someone like me.” I was devastated.

“My love for the night sky served as my reprieve.”

Social conditioning and stereotypes often discourage women, especially women of color, from pursuing careers in male-dominated fields like astronomy and physics. What’s worse, these barriers are easily internalized as insidious beliefs about ourselves, like “I’m not cut out for this.”

When I was in eleventh grade, my astrophysics teacher turned the notion of who can be a scientist on its head when he told the class that science is about curiosity. It’s the thrill of exploration, a desire to endeavor to understand the unknown. I had that, I told myself.

That curiosity is my act of resistance. It propels me, in science and life, to push beyond what is expected or known and dive into the unknown.

3. Anxiety isn’t good or bad—it just is.

I’ve struggled with anxiety ever since I can remember. It always feels like a hot pit in my stomach, a learned sense of dread descending down my spine, an enormous weight on my chest, and an inability to breathe. I wonder if I’m a failure or good enough. I wonder if I’m worthy of being alive.

Anxiety is both physical and emotional. It has made me ill and taken me to the emergency room, made me question my self-worth and reinforced toxic relationships. But anxiety has also helped me achieve my wildest dreams. It has motivated me to work hard and pursue my goals. It’s landed me in a Ph.D. program at my dream institution, in a Mars analog astronaut simulation, in a Sports Illustrated swimsuit magazine—places I never would have thought I’d belong. I’ve learned to find comfort in discomfort and lean into my anxiety; that has become my normal.

“I credit anxiety with my greatest achievements and my worst beliefs about myself.”

Anxiety isn’t good or bad—it just is. Rather than trying to eliminate it, I am learning to live in partnership with it. I credit anxiety with my greatest achievements and my worst beliefs about myself. By embracing it, I learn to embrace myself.

4. You are your own best advocate.

When I was 23, my dad was diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer. Soon afterwards, we learned that he carries the hereditary cancer-causing BRCA-2 mutation. After some blood tests, we learned that I carry it, too.

The mutation gives me an 87 percent lifetime risk of breast cancer, and over 30 percent risk of ovarian cancer. As my dad navigated his own cancer treatment, I worried that this would be my fate, too. When I was 25, I had my first breast biopsy and learned firsthand what it was like to navigate my own health journey. Thankfully, the spot of concern was benign, but in my anxiety fueled state, I recognized that I never wanted to endure that fear again. I didn’t want to wait for cancer to find me, like it had my dad and grandmother. I discovered my agency and decided to have a preventative double mastectomy.

The amputation would reduce my risk of breast cancer to less than five percent; still, many surgeons refused to meet with or operate on me. I was told that I was too young, that I didn’t have cancer yet, that I’d be removing my womanhood. Still, I pushed forward until I found a medical team that I trusted. In short, I learned to advocate for myself.

“I recognized that I never wanted to endure that fear again.”

I grieve my lost breasts, of course, but through that process I discovered that I am my own best advocate. The same is true for carving out a place for myself in science. Only I can determine what is was best for me and my body, and what I am capable of.

5. Genes remember.

The body is powerful. Not only does it represent your lived experiences, but it carries a record of the past. The stories of our ancestors can shape our body schema, and their genetic footprint continues from one generation to the next. Genes remember.

In my case, I carry the BRCA mutation lineage from my dad’s side, and that inherited risk shapes the way I live. I have gotten a double mastectomy and will screen for ovarian cancer for the rest of my life. I will approach my fertility differently because of my mutation. On my mom’s side, her anxieties and fears—many of which are shaped by being a Middle Eastern immigrant in the United States—are carried forward in my own body in the form of intergenerational trauma. Our bodies are shaped in a physical way by one another.

It is up to us to determine what we do with that. Through therapy and community building, we can break the cycle of intergenerational trauma. Through research and informed medical decisions, we can mitigate hereditary health risks. Our ancestors give us the gift of our story, but we have the agency to write our own journeys.

To listen to the audio version read by author Sarafina El-Badry Nance, download the Next Big Idea App today: