Steven Johnson is the bestselling author of thirteen books, including Enemy of All Mankind, Where Good Ideas Come From, How We Got to Now, The Ghost Map, and Extra Life. He’s the host and co-creator of the Emmy-winning PBS/BBC series How We Got to Now, the host of the podcast The TED Interview, and the author of the newsletter Adjacent Possible. He has won numerous awards for his writing and co-created the online magazine FEED, the Webby Award-winning community site, Plastic.com, and the hyperlocal media site ouside.in. Johnson regularly writes for the New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, and is a contributing editor to Wired.

Below, Steven shares five key insights from his new book, The Infernal Machine: A True Story of Dynamite, Terror, and the Rise of the Modern Detective. Listen to the audio version—read by Steven himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. We do not live in unusually polarized times.

There’s a lot of forgotten history in The Infernal Machine, but maybe the most astonishing fact from the book is that during a roughly twenty-year period at the dawn of the 20th century, New York City experienced 7,000 bombings—many of them planted by political radicals as acts of terrorism. Just imagine what that would be like in today’s world of social media and round-the-clock news coverage.

The press called the bombs “infernal machines.” This bombing campaign was not just a New York phenomenon. The period from the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881 to the Red Scare of 1919–1920 saw a surge in anarchist violence, including bombings, assassinations, and riots, that posed a significant threat to public safety and political stability. For example, over a 65-year period beginning in 1881, the number of assassinations of world leaders effectively tripled compared to the previous 65 years, with many of these acts of violence occurring in industrialized European nations and the United States.

“Over a 65-year period beginning in 1881, the number of assassinations of world leaders effectively tripled compared to the previous 65 years.”

This is all an important corrective to the idea that we live in particularly turbulent and polarized political times here in the United States. The polar opposites might be louder now—thanks to the amplifiers of social media and cable news—but they sit on a much smaller globe of political possibility. But the period I document in The Infernal Machine was a world where one side of the spectrum thought it was appropriate to execute people who objected to a 72-hour workweek in a dangerous factory, while the other side of the spectrum thought that we should abandon both governments and corporations, and reinvent society along the lines of Swiss watchmaking collectives. Those were the distant poles of the debate. What we would now call the Overton Window (the space of potentially valid political beliefs) was far wider than anything in American politics today.

2. Indexing algorithms can transform the world.

When historians catalog the momentous inventions of history—the printing press, the telescope, the steam engine—they rarely include indexing algorithms. But tools that help us explore ever larger pools of information—and widen the net we can cast in those pools—have often turned out to trigger inflection points in history. The invention of the modern footnote and indexing protocols that developed slowly over the 16th and 17th centuries made a meaningful contribution to the Scientific Revolution of that period.

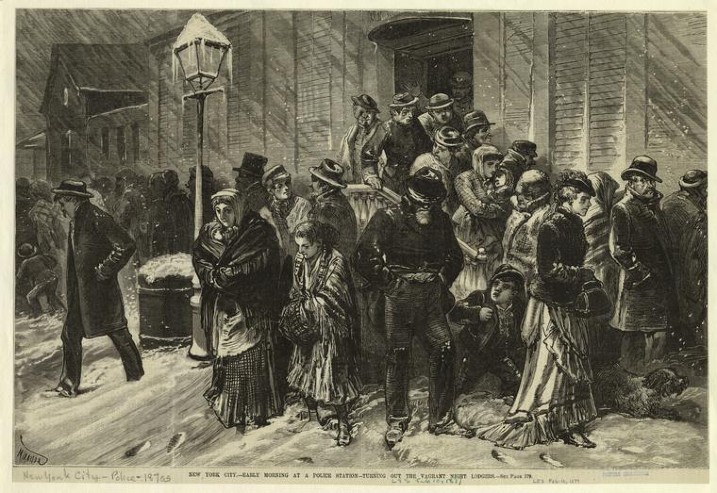

The Infernal Machine tells the story of another revolution in information management. For almost all of the 19th century, the idea of an American police officer conducting a forensic investigation—solving a crime, rather than simply beating a confession out of a suspect—would have seemed preposterous. Government agencies lacked any systematic identification systems. A suspected criminal or terrorist could simply make up a name for himself while under arrest, and the authorities would have no centralized database of information to confirm that identity.

But the pioneering work of figures like Alphonse Bertillon and Joseph Faurot transformed crime fighting into an information science, applying systematic methods like anthropometry and fingerprint analysis to track down criminals and build a more comprehensive understanding of criminal networks.

Eventually, prodded into existence by a terrifying wave of anarchist bombings in the 1910s, J. Edgar Hoover and the newly formed FBI harnessed the power of card catalogs and what Hoover called the “Editorial File System” to track and suppress anarchist activities. In the end, it was the state’s superior ability to organize information that allowed it to prevail over the anarchist dream of a stateless society.

3. How institutions change.

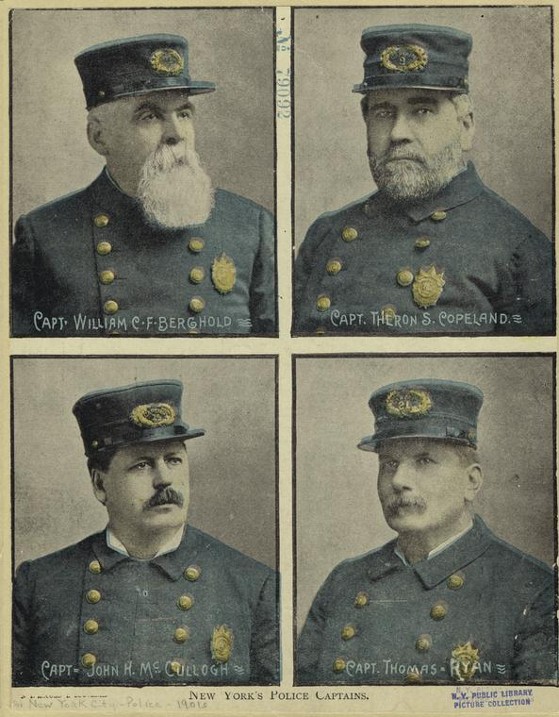

We have a default tendency to talk about large organizations (particularly government agencies) as resistant to change and innovation, but that is not always the case. There are plenty of examples in history of large organizations with entrenched habits reinventing themselves. The story at the heart of The Infernal Machine—how the NYPD radically changed the way it combatted crime over the space of about ten years—is a great case study in how institutions can transform themselves under the right circumstances.

At the close of the 19th century, the NYPD was largely characterized by corruption, inefficiency, and a reliance on brute force rather than investigative techniques. However, the emergence of anarchist violence, coupled with the pioneering innovations in forensic science in Europe, forced the department to adapt.

“It’s also an example of how massive institutions can be forced to adopt new ideas by individuals or small groups operating outside the organization.”

In part, the lesson here is the power of charismatic individuals inside the organization (like Joseph Faurot, who championed the adoption of fingerprint identification and other forensic methods) gradually shifting the NYPD towards a more scientific and data-driven approach to crime fighting. Or police commissioner Arthur Woods, who spearheaded the creation of specialized units like the Bomb and Anarchist Squad, embracing undercover operations and a more strategic approach to containing radical threats.

It’s also an example of how massive institutions can be forced to adopt new ideas by individuals or small groups operating outside the organization. One of the main reasons I wrote this book was to document the extent to which these vast modern surveillance systems were brought into being by the threat posed by rogue anarchist groups. It’s one of those stretches of history where some of the most powerful institutions in the world were shaped by the activities of marginal groups working outside the dominant channels of power.

4. Innovation’s unforeseen paths.

As my thinking on innovation has evolved, I’ve become increasingly interested in how new ideas, however brilliant, sometimes confound the expectations of their creators.

There’s an incredible story of technology’s unintended consequences: the story of Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite. Nobel envisioned his creation as a tool for progress, aiding construction and engineering projects. He believed dynamite’s destructive power would deter warfare, leading to a “golden peace.” However, the compact and easily concealed nature of dynamite made it the weapon of choice for a new breed of political radicals and anarchists, giving them the ability to challenge powerful institutions. The unintended consequences of Nobel’s invention were profound, sparking a wave of terrorist attacks that swept across Europe and eventually reached America.

Ultimately, Nobel’s legacy became intertwined with the violence he had inadvertently unleashed, earning him the moniker “the merchant of death.” Seeking to reshape his legacy and promote peace, Nobel established the Nobel Prizes, including the prestigious Peace Prize, which recognizes efforts towards disarmament and conflict resolution.

The story of dynamite serves as a stark reminder that even the most well-intentioned innovations can have unforeseen and far-reaching consequences. When we bring new technology into the world, we need to be thoughtful about not just how it can help us but how it could be co-opted in potentially negative ways.

5. History happens when different cultural networks collide.

History often unfolds at the crossroads of seemingly disparate worlds. The early 1900s in New York City provides a striking example where European anarchism, Nobel’s dynamite, and European forensics all converged, shaping the city’s trajectory and the broader course of American history. Anarchism, with its vision of a society free from hierarchies and state control, arrived in America with European immigrants like Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. These idealists sought to dismantle both the capitalist system and the power of the state. Their movement coincided with the widespread availability of dynamite, thanks to Alfred Nobel’s invention. Nobel’s pursuit of a stable explosive for engineering projects inadvertently gave anarchists a powerful weapon.

“This convergence of ideologies and technologies in New York City created a clash between anarchists and the emerging surveillance state.”

Europe also provided the tools to combat this new form of terrorism. Forensic science, pioneered in Paris by Alphonse Bertillon, offered a “scientific” approach to crime-fighting. Inspired by these European innovations, Joseph Faurot championed the adoption of fingerprint identification and other forensic techniques within the NYPD.

This convergence of ideologies and technologies in New York City created a clash between anarchists and the emerging surveillance state, with figures like Faurot and Berkman at the forefront of this struggle. The outcome of this clash would have profound implications for the future of policing, political dissent, and the balance between individual freedom and state control.

To listen to the audio version read by author Steven Johnson, download the Next Big Idea App today: