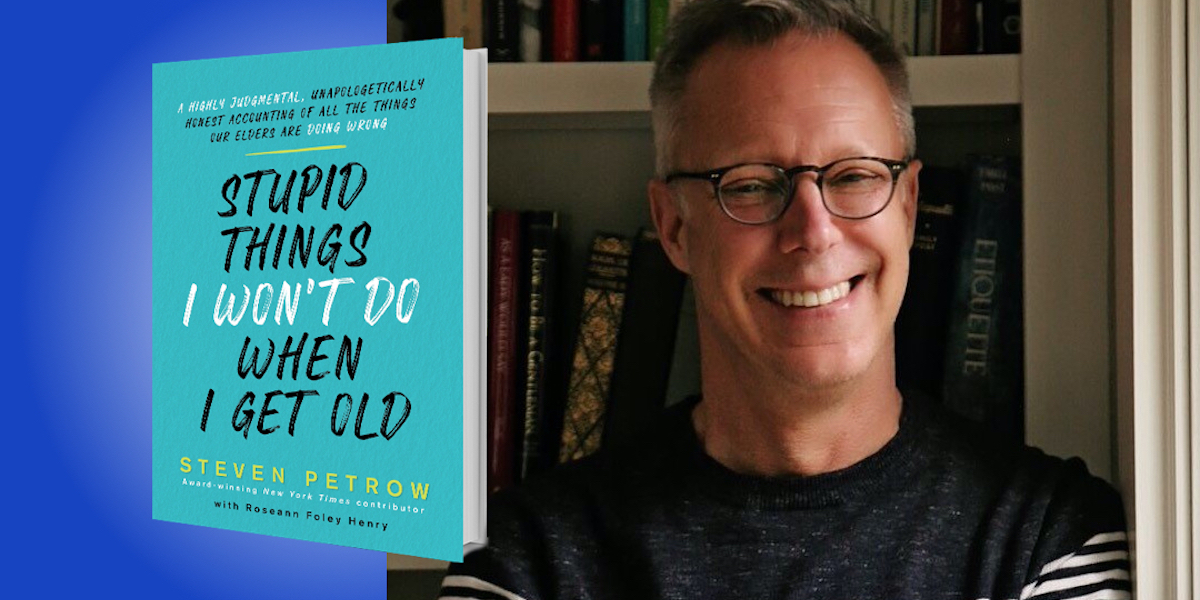

Steven Petrow is an award-winning journalist and author best known for his Washington Post and New York Times essays on aging, health, and civility. He’s currently an opinion columnist covering manners and civil discourse for USA Today, and his 2019 TED Talk, “3 Ways to Practice Civility” has been viewed nearly two million times and translated into 16 languages. He is formerly the president of The Association of LBGTQ Journalists, and his previous book was about navigating LGBT life. In his new book, Petrow analyzes how his parents approached aging, and teaches himself (and us) how to be better at growing old.

Below, Steven shares 5 key insights from his new book, Stupid Things I Won’t Do When I Get Old: A Highly Judgmental, Unapologetically Honest Accounting of All the Things Our Elders Are Doing Wrong (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Steven himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Don’t double-space after a period.

Okay, I know that seems highly specious, but this “stupid thing” is actually a proxy for, “Don’t become a Luddite.” I’m not saying that you need to become an IT expert or develop apps in your spare time, but we do need a basic proficiency to use our smart phones, watch our smart TVs, read on our Kindles, and to post, tweet, stream, SMS—even TikTok!

Now, here’s the double-space problem: I’m 63, and like almost everyone in my generation, I learned to type on a manual typewriter, always inserting a double-space after a period. That way you could see where the next sentence began. Thanks to Grandma Marian, my typing teacher, the rule became embedded in my DNA. But for a long time now, computers use what are called “proportionally spaced fonts,” which means the spacing is adjusted to the size of the letter. That means there’s no reason to double-space anymore.

Let me be brutally honest: It’s hard for Boomers to retrain our brains to do that. But here’s the point: Nothing shouts that you’re old—or stuck in your ways—more than that double-space. My co-author admits, “I do it so automatically that I don’t realize it until I see a printout. But then that extra space stands out like the parting of the Red Sea.”

“Our fumbling with new devices, operating systems, QR codes, and social media platforms is what truly marks us as Luddites.”

We don’t just need to drop outdated practices; we need to embrace—or at least learn—new ones. These days, new almost always means tech. Our fumbling with new devices, operating systems, QR codes, and social media platforms is what truly marks us as Luddites.

Look, I’m right there with you, but I know I have to keep plugging away so I don’t get left behind as, what my “AppleBuddy” (a young tech wizard) called me not long ago, “ancient history.” For instance, my mom struggled with her devices. I remember the birthday when she asked my siblings and me for a Kindle. We knew she’d never master it, but Mom took great pleasure in telling all her friends that we’d given her that device. I still have the email she sent, which ended with “LOL.” To Mom, LOL always meant “lots of love.”

2. When you need help, get help.

At 45, I needed reading glasses, and I got them. In my mid-50s, I’d moved on to progressives, and I spent the big bucks to get a pair. A writer and colleague of mine, Jenny Boylan, recently pointed out a quandary of our times: Why is it that devices to keep us from being blind are celebrated as fashion, but devices to keep us from going deaf are considered embarrassing and uncool?

I know, we have so many reasons not to use hearing aids—they’re uncomfortable. They’re ugly. They whistle. They hurt. They’re expensive. But worst of all, they make us seem “old and undesirable.”

For the last chapter of my dad’s life he—a former TV producer—would shout at me, in fact, at everyone in the family, “Up your audio!” It was always us, never him. That’s a clue. Even when I explained to Dad that the newest hearing aids are practically invisible, he still would not listen. Or perhaps he didn’t hear me. Over time Dad became disconnected from the rest of us. He couldn’t follow dinner time conversations, or talk on the phone with his friends.

“Untreated hearing loss has serious emotional and social consequences for older people—conditions like depression, anxiety, and paranoia.”

More than one-third of those over 65 need a hearing device but are not using one. Only later did I understand that untreated hearing loss has serious emotional and social consequences for older people—conditions like depression, anxiety, and paranoia. Sometimes, we have to make a small sacrifice for a greater gain. I wish I’d been able to get my dad to hear that.

3. Don’t become a burden to your loved ones.

My parents lived in a house on a cliff. That is not a metaphor. It also had many steps, narrow doorframes, and uneven floors. We worried: What if they fell? Took ill? What if one died, leaving the other alone? My siblings and I suggested they look into a continuing care community, where residents live independently until they need more assistance. My brother even took them on a tour of a nice facility near him, where on the dinner menu that particular night was “sake tamarind-infused Chilean sea bass.”

After the tour, Jay queried them, “What do you think?” In response, Mom said, “I hate fish.” And Dad added, “Never, we will age in place,” followed by the then much-repeated refrain from their last years, “We don’t want to become a burden to you.”

And so they stayed, perched high on their cliff. For the next decade we managed their finances, hired and fired health aides, and fielded emergency calls 24/7—which were so frequent and exhausting that we took turns being “on-call.” Still, we kept hearing: “We don’t want to become a burden.”

A lot of us think we can age in place. In fact, 90% of older Americans say that. I was one of them. After my divorce—which also meant the loss of my at-home caregiver—I bought a one-level house. But as a gay man without kids, I faced a daunting conundrum: Who will take care of me when I can’t?

I decided to take a look at one of these communities. All the units, from villas to apartments, were clean and well-kept. I noticed ramps covering steps and grab bars hanging in shower stalls. The dining room boasted plenty of food options—a shrimp scampi buffet!—but I couldn’t help noticing all those relying on canes, walkers, and rollators. Another fellow on the tour whispered: “I’d rather kill myself than live here.”

“Older adults who hold negative views about their own aging live, on average, 7.5 years less than people with positive views.”

Before we continued on to the skilled nursing facility, I bailed. I just couldn’t go there. I understood better than before why my parents couldn’t make such a move—it wasn’t about that Chilean sea bass. But I also didn’t want to be the brother or uncle—or perhaps spouse again—who said, “I don’t want to become a burden,” and then proceed to become just that. A friend, then 85 and in her first year in one of those communities, gave me some advice: “Write the deposit check, and forget about it.” That’s what I did. Now, I have a plan. I’m relieved, and I’m guessing my three nieces are, too.

4. Stop with those “stupid/funny” birthday cards.

For many years I’d send friends fifty-plus “funny” cards like this: “I don’t know how much time you have left, so I’ll keep this brief. Happy Birthday.” I complimented some of those same friends by insisting they didn’t look their age—as if their real age were a bad thing. And then after my divorce, I lied about my age as I signed up for dating apps.

I didn’t see the connective thread until recently, when I realized I’d fallen prey to what’s called “everyday ageism.” This reinforces the stereotype that old is bad and young is good. I read the recent findings of a University of Michigan poll on aging, which reported that more than 80 percent of older Americans routinely experience ageism in their day-to-day lives. This includes dismissive quips about us not being able to use our smart phones properly, jokes about losing our memories or hearing, and the proliferation of anti-aging messages in mass media.

Can’t we take a joke? Sure, but there’s a cost to all this. According to an AARP researcher I spoke with, the more people run into ageist thinking and age discrimination, the more they start to second-guess their abilities, become depressed, and even develop chronic conditions like diabetes or heart disease. More disturbing, according to the World Health Organization, older adults who hold negative views about their own aging live, on average, 7.5 years less than people with positive views. According to that, ageism is as harmful to our health as smoking.

“We do an injustice to ourselves—not to mention our well-being and longevity—to conflate illness and aging.”

5. Don’t join the “organ recital.”

It can happen anywhere, at any gathering, any time a few people of a certain age get together. First the fanfare: “What’s new with you?” Then the overture: the high cholesterol, the pre-diabetes, and the bum knee. Before you know it, the music swells and it’s a full-blown concert of sciatica, angina, and replacement joints. Welcome to the front row of the worst musical revue imaginable. Yes, you’re at an “organ recital.”

How did this happen? It wasn’t that long ago that we talked incessantly about our kids, our vacations, and our jobs. Is the organ recital really so different?

Not entirely. It is, after all, an extension of our lifelong self-absorption. But here’s the challenge: The more we define ourselves by our frailties and illnesses, the more we allow them to become us. Of course, illness is part of our lives—and more so as we age. I’m all for disclosure when it comes to what ails us. After suffering from depression for decades, I finally began acknowledging it to others in my writing—when I was 59. 59! I found so much relief in sharing this part of me. Even more rewarding, friends have been much more forthcoming about their own mental health issues. Still, as much as depression has left its imprint on me, I will not let it define me.

I also won’t conflate illness with aging. They are two very distinct things. You can become sick or disabled at any time in life. (I know—I had cancer in my twenties.) Aging, or simply being older, is a life stage—kind of like pregnancy—but hopefully longer.

To this point, in recent years I’ve watched close friends, colleagues, and celebrities die prematurely. They had not even had the opportunity to become old. I specifically remember when Phyllis George, the pioneering sportscaster and former Miss America, died at age 70, and a college friend, who is exactly my age, texted, “That proves we’re old.”

“No, no,” I quickly replied. “Phyllis George had this form of cancer for thirty-five years. She was ill.” We do an injustice to ourselves—not to mention our well-being and longevity—to conflate illness and aging. I’m reminded here of what Gabriel García Márquez once wrote: “It is not true that people stop pursuing dreams because they grow old; they grow old because they stop pursuing dreams.”

To listen to the audio version read by Steven Petrow, download the Next Big Idea App today: