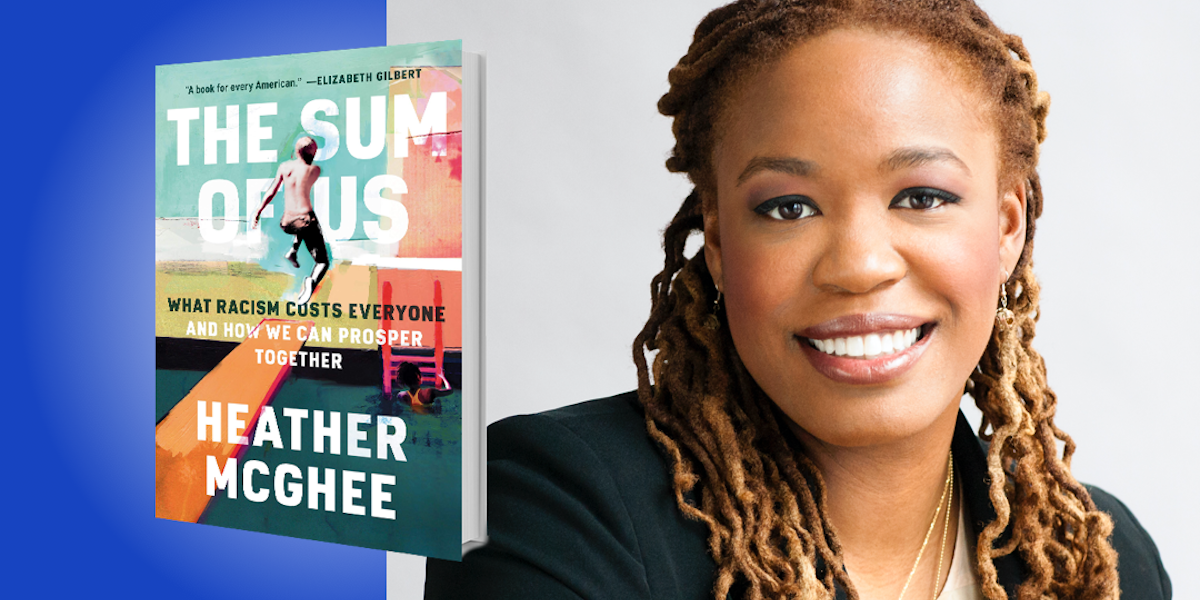

Heather McGhee is the former president of Demos, a “think-and-do” tank that generates progressive ideas, produces original research, and builds grassroots toolkits. A graduate of Yale University and the University of California Berkeley School of Law, she currently chairs the board of Color of Change, the largest online racial justice organization in the country.

Below, Heather shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together (available now on Amazon). Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. It’s not just you.

Americans can’t seem to have nice things. And by “nice things,” I don’t mean laundry that does itself or hovercraft backpacks. I mean the most basic aspects of a high-functioning society, from a robust public health system to deal with pandemics to reliable modern infrastructure, a well-funded school in every neighborhood, or wages high enough to keep workers out of poverty.

It wasn’t always this way. In the mid-1960s, when white people made up almost 90% of the population, government investment in the public good was seen as a positive. The U.S. had a high minimum wage, subsidized home ownership, good union jobs, strong financial protections, and a tax rate sufficient to fund research, infrastructure, and education.

But as the civil rights movement gained steam and the white population declined, our overwhelmingly white policymakers began to reconsider just how deserving the public really was. They instituted rapid changes to tax, labor, and trade laws that gave rise to today’s inequality era in which 40% of people aren’t paid enough to meet their basic needs, and the top 1% owns as much wealth as the entire middle class.

“40% of people aren’t paid enough to meet their basic needs, and the top 1% owns as much wealth as the entire middle class.”

2. The zero-sum racial hierarchy.

The most significant impediment to our progress is a lie: the zero-sum racial hierarchy. To deprive all Americans of the government investments that support a decent life makes sense only if you believe in the idea that we’re trapped in a zero-sum game, and any improvement for people of color must come at the expense of white people. This idea is rooted in our nation’s history. From our colonial beginnings, the U.S. economy depended on stolen land and stolen labor. Progress for those considered white came at the expense of people considered non-white. This made it easy for the powerful to sell the idea that the inverse was also true—that liberation or justice for people of color would require taking something away from the masses of white people. This racial zero-sum story persists to this day.

3. We are suffering from drained-pool politics.

From the 1920s through the 1940s, towns and cities across America built resplendent resort-style public swimming pools. It was part of a New Deal-era social contract that said that government ought to ensure a higher standard of living for our people.

Consider the Oak Park Pool, which was once the crown jewel of the Parks Department in Montgomery, Alabama. In 1958, Montgomery faced court action to integrate the pool. Black residents said, “Those are our tax dollars. Our kids should be able to swim too.” Instead, the city council decided to drain the pool rather than share it with their Black neighbors. They closed the entire Parks Department and kept it closed for over a decade.

“The city council decided to drain the pool rather than share it with their Black neighbors.”

Countless other towns across the U.S., from Ohio to Washington, took similar steps. These communities lost public assets, and so did every family, both white and Black, that was not rich enough to build backyard pools or join the membership-only swim clubs that cropped up across the country. The spirit that drained these public pools lives on, and is reflected in America’s willingness to drain pools of resources.

4. Racism has a cost for everyone.

Did you know that college used to be free? For generations, college-going white Americans could count on public money from federal or state governments to pay most, if not all, of the costs of their higher education. As late as 1976, state governments provided six out of every ten dollars of the cost of public college. What was left—an average of $617 at a four-year college in 1976—could be covered by a federal Pell Grant.

When “the public” meant “white,” public colleges thrived. But as the proportion of students of color in public colleges grew from one in six in 1980 to four in ten today, support for ensuring college affordability fell among lawmakers, who began to slash what they spent per student. By 2017, the majority of state colleges were relying on student tuition dollars for most of their expenses, even as the cost of the average public college tuition nearly tripled since 1991.

Eight in ten Black graduates have to borrow, but student debt has now reached six out of ten white public college graduates, too, stopping a whole generation from buying homes, marrying, starting families, and saving for their retirement.

“Communities that are racially divided can’t muster the power to win the policies they need, often leaving wealthy private interests to set the rules.”

5. The solidarity dividend.

The idea of government is to help us achieve things that we can’t achieve on our own. I can’t create my own internet or electric grid or interstate highway system, but I can vote and advocate for policies that, with enough citizen support, make these things possible. I call these advances “solidarity dividends.” They’re gains that can only be unlocked through collective action, but communities that are racially divided can’t muster the power to win the policies they need, often leaving wealthy private interests to set the rules.

Take Richmond, California. North Richmond, which is 97% people of color, has disproportionately higher rates of cancer and asthma, and receives the bulk of its pollution from Chevron and other local industries. But when I examined the data for nearby neighborhood Point Richmond, which is predominantly white and wealthy, I found the same toxins in their air. We live under the same sky.

To protect their land, water, and air, residents of Richmond needed to come together and exert some authority over Chevron’s operations. It wasn’t easy, but they did it, carefully identifying their shared concerns and building trust across racial lines.

That multiracial coalition elected a mayor and a city council who stood up to Chevron, blocked a major plant expansion, and won community benefits that include a 60-acre solar field owned by the public. Richmond’s solidarity dividend has resulted in cleaner air, new jobs, and the chance for better health for everyone.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: