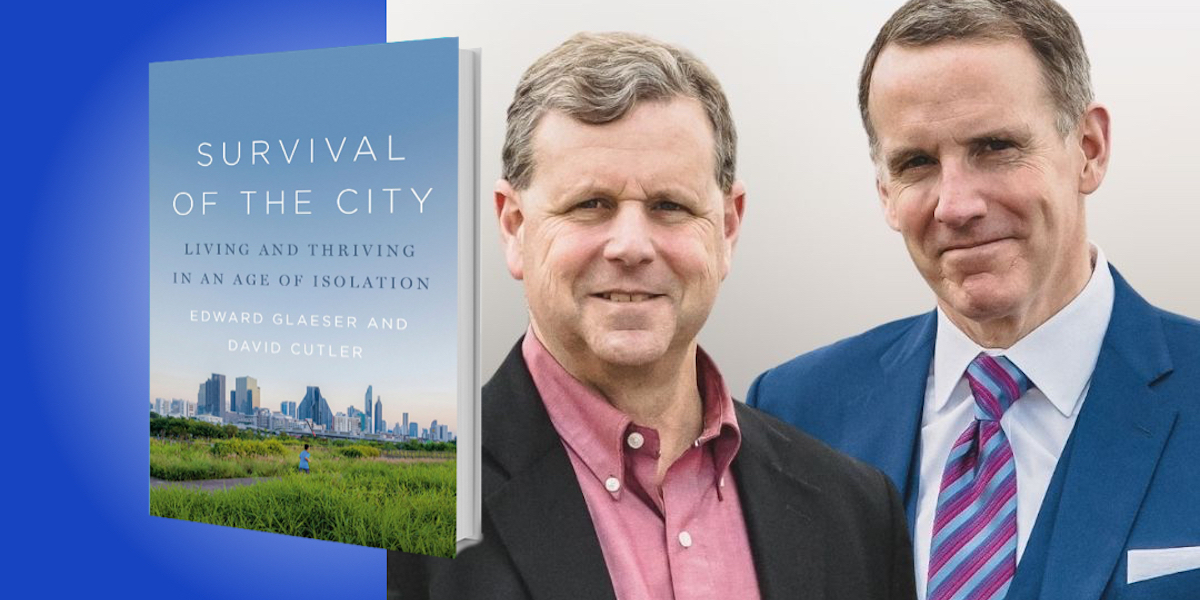

Edward Glaeser is the Fred and Eleanor Glimp Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics at Harvard University. He leads the Urban Economics Working Group at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and co-leads the Cities Programme at the International Growth Center. David Cutler is the Otto Eckstein Professor of Applied Economics in the Department of Economics at Harvard University. He has served on the Council of Economic Advisors and the National Economic Council and has advised businesses and governments on health care.

Below, Edward and David share 5 key insights from their new book, Survival of the City: Living and Thriving in an Age of Isolation. Listen to the audio version—read by Edward and David themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. We need cities—but they’re vulnerable.

At their heart, cities mean density, proximity, and closeness among people. For that reason, and because cities are the nodes on our global lattice of travel and transport, cities will always be extraordinarily vulnerable to pandemics. But the impact of a pandemic, like the impact of any natural disaster, is determined by the strength of society. The plague of Athens toppled the city from its glittering spot atop the Mediterranean world because illness struck when the city was at war with Sparta. The plague that hit Constantinople 1,000 years later was even more catastrophic because the collapse of the Roman Empire had left society so weak. The COVID pandemic and the ensuing shift to telecommuting feel so dangerous because our urban world has never been so divided.

There is no risk that humanity is going to stop being an urban species. We work better, we play better, we invent better, and we live better when we are in the company of others—but every city is vulnerable because it has never been easier for firms to move somewhere else, and for the wealthy and well-educated to just Zoom it in.

So for cities to survive and thrive, they need to up their games and provide more for those who have less without overtaxing those who have more. That means speeding the permitting of new buildings and new businesses, and being smart about improving educational options—we like experimental vocational programs that wrap around traditional schools and provide the skills to be a plumber or a programmer. This also means making the institutional reforms needed to ensure that our police deliver both public safety and basic respect for everyone—of every color and in every neighborhood.

“We work better, we play better, we invent better, and we live better when we are in the company of others.”

2. Let’s put the “health” in health care.

One might guess that a $4 trillion per year health care system would provide comfort when a pandemic strikes. The US has the fanciest health care system around, but it fell apart when it counted the most. The US has 4% of the world’s population, but has experienced 14% of the COVID deaths.

The reason for the failure is that the health care system is not a “system” in any real sense. Rather, it’s a program to ensure that medical bills are paid. If those bills reflect services that improve health, that’s good—but the system does not go out of its way to make sure that is what happens.

One of the most striking features about health care is how little involvement the payers for care have in what happens. Federal, state, and local governments in the US spend over $1 trillion annually on medical care, yet the management of that spending is weak. Mostly insurance pays for what’s done by doctors, quibbling here and there about the price and value. Contrast that with the Defense Department, which decides what it wants to buy in contracts for equipment. Or consider health care in other countries, in which the government is far more involved. The Defense Department gets what it wants, while Medicare does not.

We also need to invest far more in the public health system. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the nation’s premier public health authority, has a budget that’s approximately the size of a large hospital system in Boston. If one runs a public health system on a shoestring, one suffers when the string wears thin—and that’s what happened during COVID. Early in the pandemic, the CDC produced tests to detect COVID. Alas, the tests were faulty, and because the CDC was the only game in town, crucial time was lost. Later on, the CDC was beaten down by an administration that didn’t want news of the pandemic to be heard. And even today, the CDC gives confusing guidelines about what’s safe for children and schools and other aspects of prevention.

The distinction between public and private health made sense a century ago, when doctors tended to the sick and pregnant while public health officials built water and sewage facilities. It makes no sense today. Well-run countries like South Korea integrate their testing and treatment facilities to prevent the spread of COVID. Public health in the US will need to move from an afterthought to a central part of medical care, taking money from medicine if need be.

“If one runs a public health system on a shoestring, one suffers when the string wears thin—and that’s what happened during COVID.”

3. It’s time to slash rules that protect insiders and constrain outsiders.

Our cities are divided between rich and poor, African-American and white, young and old. House-price booms have enriched homeowners and left renters facing ever-mounting costs. The knowledge workers of technology and finance have seen spectacular wage gains, while poor urban children experienced dismal levels of upward mobility. The natural response to such inequality is to take from the rich and give to the poor. But when cities have tried to do that, then the rich just leave—and Zoom has made that easier than ever.

Luckily, today we can both help the poor and strengthen urban economies by reducing the rules that protect insiders and harm outsiders. It is outrageous that America regulates the entrepreneurship of the poor so much more than the entrepreneurship of the rich. After all, you can start an internet phenomenon in your Harvard dorm room without any oversight, but try to open a grocery store five blocks away, and you need over 15 permits.

We have an affordable housing crisis because we have rules that stop new building, to protect the neighborhoods and views of entrenched homeowners. But construction doesn’t have to be overly constrained by regulation—New York City rents stayed reasonable during the 1920s, when the city permitted more than 100,000 units per year. Today, we can boost building and allow room for outsiders simply by speeding the permitting process. Our cities, and especially the outsiders, need the freedom to flourish.

4. We need a NATO for health.

If the world does not act forcefully, potential pandemics like COVID-19 will become a regular occurrence. Travel is simply too rapid and human-animal contact too widespread to prevent outbreaks from turning into pandemics. And the problem is not confined to China: Ebola and HIV came from Africa, H1N1 was first spotted in Mexico, so-called Spanish flu likely originated in Kansas, and the Delta variant of COVID was first identified in India.

“China is a big funder of the WHO, and the WHO wants to keep the funds flowing. But where infectious disease is concerned, science and politics should not mix.”

Multinational problems demand coordinated solutions. Our idea is to address the newest of problems by borrowing from the most successful global alliance of the past century, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. After World War II, there was fear that the Communists would invade Western Europe, and an alliance was set up to prevent this. NATO had a clear mission, and rules directed to that mission. There’s been peace in Europe ever since.

There is, of course, a World Health Organization. WHO has done many things well, including helping to eradicate smallpox, but the WHO underperformed during COVID-19. The WHO believed the claims of the Chinese, who asserted that COVID-19 could not be transmitted human to human. It also advocated against limiting travel from China. Politics seems to be at the root of the problem, as China is a big funder of the WHO, and the WHO wants to keep the funds flowing. But where infectious disease is concerned, science and politics should not mix. The world needs an organization focused on the science of preventing pandemics, and that organization must have a budget secure enough to leave politics aside.

The mission of a NATO for health would be difficult. After all, only a few countries can start a war; any country can be the source of a pandemic. Thus, there need to be global regulations on the interactions between human and animals, requirements for rapid reporting of infectious disease outbreaks, commitments to early quarantines and mass population testing, and huge investments in public health infrastructure, including sanitation and water cleanliness. Realistically, only the rich countries can afford to pay for this. The cost to the US is likely to be tens of billions of dollars per year, but the gains to preventing pandemics are enormous. For comparison, COVID-19 cost the US roughly $16 trillion in lost output and premature mortality.

So in exchange for money, rich countries would get assurances that all reasonable safety precautions are being taken. They would also have the right to impose sanctions. If a country were not behaving according to the rules, movement of people and goods out of the country would be restricted. Perhaps travel could occur only through one city, with testing of everyone leaving. Goods might be held in quarantine until it was clear they were safe. First-tier access to the world economic system would be reserved for those who ensure the safety of the world’s health.

In short, if we want to avoid a major setback in health, we need to set the rules so that good health is prioritized. What other choice do we have?

“COVID-19 cost the US roughly $16 trillion in lost output and premature mortality.”

5. Education and police institutions need dramatic reform.

The Opportunity Atlas created by Raj Chetty and his coauthors finds that children who grow up just inside big city school districts earn significantly less as adults—and are more likely to wind up in prison—than children who grow up just outside the borders of those districts. At the national level, we have tried both Republican and Democratic fixes, but big city school systems are very resistant to change. Reforming these schools feels like running at a brick wall, so why not run around the wall with experimental vocational programs that teach after school, on weekends, and over the summer? We can ask trade unions, for-profit companies, and community colleges to develop courses to teach kids to be programmers and plumbers. These courses can compete, and since you can measure whether someone knows how to code or to fix a pipe, you can pay only for performance.

As for our police forces, while big city crime rates have fallen dramatically since the 1980s, safer streets have come at the expense of millions in prison and bitter relations between the police and many communities. Just look at the murder of George Floyd, which sparked a national movement where millions took to the streets. Yet defunding the police makes little sense; we actually want our police officers to do more, not less. We want them to prevent crime, and to treat every citizen with respect.

The key is to change the incentives. Today, police chiefs are evaluated on the basis of crime rates, but they should be evaluated both on crime rates and on public satisfaction with police behavior. They need a dual mandate, and we must fire police chiefs who fail to achieve along both dimensions.

Fixing our government isn’t easy, and it won’t be quick. But if we aren’t willing to patiently focus on improving core public services, then we will continue to have a public sector that costs far too much and delivers far too little.

To listen to the audio version read by Edward Glaeser and David Cutler, download the Next Big Idea App today: