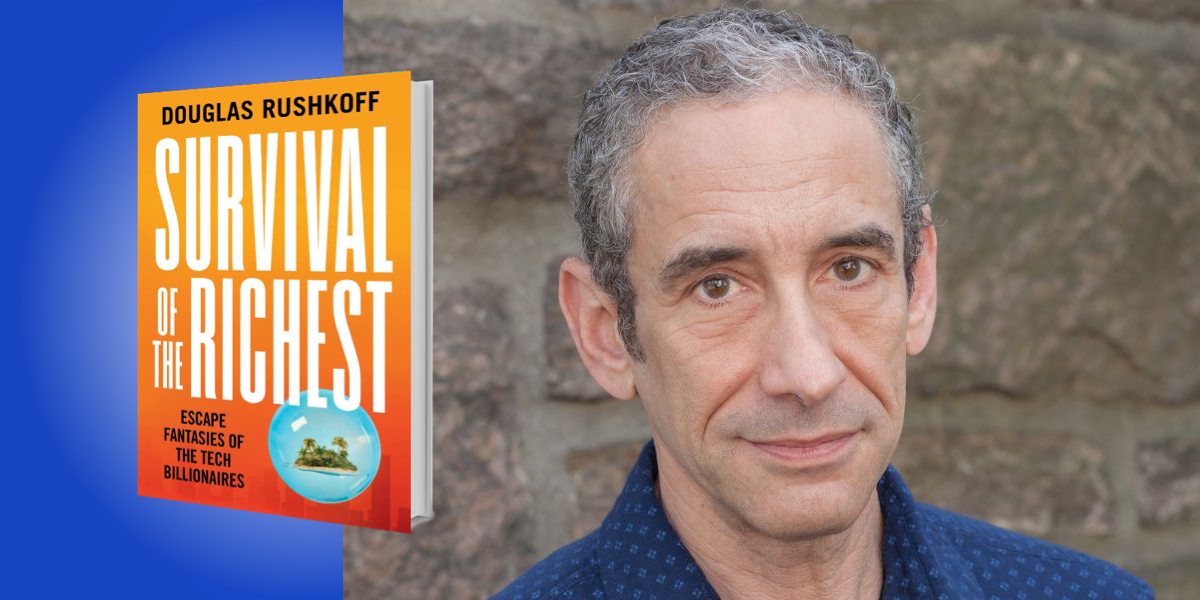

Douglas Rushkoff is professor of media theory and digital economics at Queens/CUNY. Named one of the world’s 10 most influential intellectuals by MIT, he has been exploring, celebrating, and bemoaning tech development since the early 1990s. He hosts the Team Human podcast and has authored 20 books.

Below, Douglas shares 5 key insights from his new book, Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires. Listen to the audio version—read by Douglas himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Don’t fall for The Mindset.

I gave a talk for a small group of tech billionaires who wanted to know how best to prepare for the “event”—the crisis that destroys civilization. They see such a catastrophe as inevitable but—for a select few—survivable.

So instead of spending their energy trying to keep the world from crumbling, they’re looking for ways to escape the disaster of their own making. This is what I call The Mindset: a belief that with enough money and technology, wealthy men can live as gods and transcend the calamities that befall everyone else. It’s a way of applying the “exit strategy” of a Silicon Valley startup to civilization itself.

The Mindset is rooted in empirical science: the reduction of nature and complexity, the domination of others, and the extraction of substance and energy from the real world and its conversion into symbol systems, like money. Digital technologies catalyzed and amplified The Mindset, yielding tech billionaires who believe that they can lord over us and then leave us behind as they migrate to humanity’s next phase of existence.

What I found out at my strange meeting with them is that the billionaires at the top of these virtual pyramids actively seek the endgame. In fact, like the plot of a Marvel blockbuster, the very structure of The Mindset requires an endgame. Everything must resolve to a one or a zero, a winner or loser, the saved or the damned. Imminent catastrophes, from the climate emergency to mass migrations, support their mythology and offer an excuse to live out their fantasy of escape.

2. Beware of the insulation equation.

Epson claims there’s an internal sponge in your printer that soaks up extra ink, and that once it’s saturated it could start an electronic fire. This is not true—and even if it was, a sponge can be replaced. The company wants to make us buy more printers, even if it means piling up old ones in mountains of toxic waste.

“The majority of humanity and nature can’t be discarded like the first stage of a rocket ship.”

The human executives believe they can somehow outrun the catastrophes of their own making. But the only way they can do that is by becoming billionaires wealthy enough to build bunkers, seasteading communities, rocket ships, or computing clouds capable of hosting their brains. To earn enough money fast enough to outrun the apocalypse, they engage in reckless business practices. It’s like they’re trying to build a car that goes fast enough to escape its own exhaust. They’re operating by what I call the insulation equation: how much money do I need to escape from the disasters I’m bringing on by earning money in this way?

Unfortunately, real disasters don’t respect the guardian boundary on their Oculus VR. The majority of humanity and nature can’t be discarded like the first stage of a rocket ship. In the old days, if you lived in a bad neighborhood you might strive to earn enough money to move to a better one. But what about when the world itself is turning into a bad neighborhood? You can’t move away; you have to address the problems.

3. Watch when they go meta.

The tech billionaires have one thing in common: when they run out of ideas, resources, or people on one level, they go meta. This is what was originally meant by Web 2.0: instead of competing with all the other internet businesses, go meta on the industry and create the platform that aggregates all these businesses and houses their competition. It’s what Peter Thiel means when he says to go “from zero to one”—you operate “an order of magnitude” above the competition. It’s why when Facebook’s user growth begins to wane, Mark Zuckerberg announces he’s literally going Meta, creating an as-yet undefined virtual world that will encompass everything.

Going meta is the hallmark of the digital economy and The Mindset. The Industrial Age was all about linear growth. Industrialists were able to outrun the externalities of their businesses. Chartered monopolies colonized a territory, vanquished its people, extracted their resources, and then moved on to the next one. As long as there was more world to conquer, businesses could grow. Eventually, though, they ran out of room.

The financial sector understood this first. That’s why they developed abstract stock shares to represent physical ownership, then derivatives to go meta on stocks, derivatives of derivatives, credit default swaps, and so on. The derivatives market became so much bigger than the stock market that a derivatives exchange actually purchased the NYSE in 2013. The stock exchange (which was already an abstraction of the marketplace) was consumed by its own abstraction!

“Those committed to the meta-verse often believe that it’s okay to sacrifice real reality to these symbols.”

Digital technology lets us go meta on physical reality. It’s a symbol system—a map, not the real territory. While it’s removed from reality, it is also limitless, and the perfect landscape in which to attempt to scale money infinitely. But because it is not grounded in reality, those committed to the meta-verse often believe that it’s okay to sacrifice real reality to these symbols—like burning the planet to demonstrate our faith in a digital representation like bitcoin.

4. Wealth erodes empathy.

Studies are showing that billionaires don’t identify with the pain or emotions of others. The empathic parts of their brains don’t light up when they witness another human in distress. They can’t read the emotional states of others. It’s as if they hurt their frontal lobes—they have brain damage.

This could be because “winning,” in their scheme, means leaving others behind. The extreme sort of wealth they seek—enough to have not just a super yacht but a second yacht to service the super yacht—means separating from the rest of humanity. They have the technology to fulfill this need for isolation, and perpetuate the cycle of disassociation. As Timothy Leary commented when he read Stewart Brand’s book about MIT’s Media Lab, “these guys want to recreate the womb, only with technology.”

The technologies they build and we use are informed by this anti-human, anti-empathic sensibility. The Mindset trickles down to us—particularly during crises—making us embrace the Amazon video doorbell, DoorDash deliveries, and Zoom calls.

The more we interact on Zoom, the less empathy we feel ourselves. On a Zoom call, unlike in real life, we can’t see if someone’s pupils are getting larger as they take us in, if their breathing rate is syncing up with ours, or any of the other painstakingly evolved social cues we use to establish rapport. The mirror neurons in our brains don’t fire, the bonding hormone—oxytocin—isn’t released, and we don’t feel connected. If anything, when the person says they agree with us and we don’t get physiological confirmation, we become anxious and distrustful. We erode our own empathy circuits.

5. Embrace reality.

We don’t have to surrender to the idea that the planet is doomed and only the wealthy will survive. We can still make it. Don’t believe them—they’re just scared because their own business plans require the destruction of our world. The devices and platforms they are making are amazing, but the real world is coming apart. And the people who make these screens not only know they are the cause—they also think our last best hope is to double down and apply even more technocratic, totalizing solutions to the world’s problems.

“We’re only in crisis because the map has replaced the territory; the virtual reality matters more than the real reality.”

The easier way is not get out, but go through. We can stop supporting their companies and the way of life they’re pushing. We can do less, consume less, travel less—and make ourselves happier in the process. Buy local, engage in mutual aid, and support cooperatives. Use monopoly law to break up anticompetitive behemoths, environmental regulation to limit waste, and organized labor to promote the rights of gig workers. Reverse tax policy so that those receiving passive capital gains on their wealth pay higher rates than those actively working for their income.

Everything down here on the ground could be just fine if we weren’t burdened with satisfying the needs of the abstracted map we created to represent our world for the benefit of the obscenely wealthy. We are not up against the limits of our physical reality, but the limits of our digital balance sheets. We’re only in crisis because the map has replaced the territory; the virtual reality matters more than the real reality. Instead of providing for our security, our financial and technological systems are now the greatest threats to our collective well-being.

To listen to the audio version read by author Douglas Rushkoff, download the Next Big Idea App today: