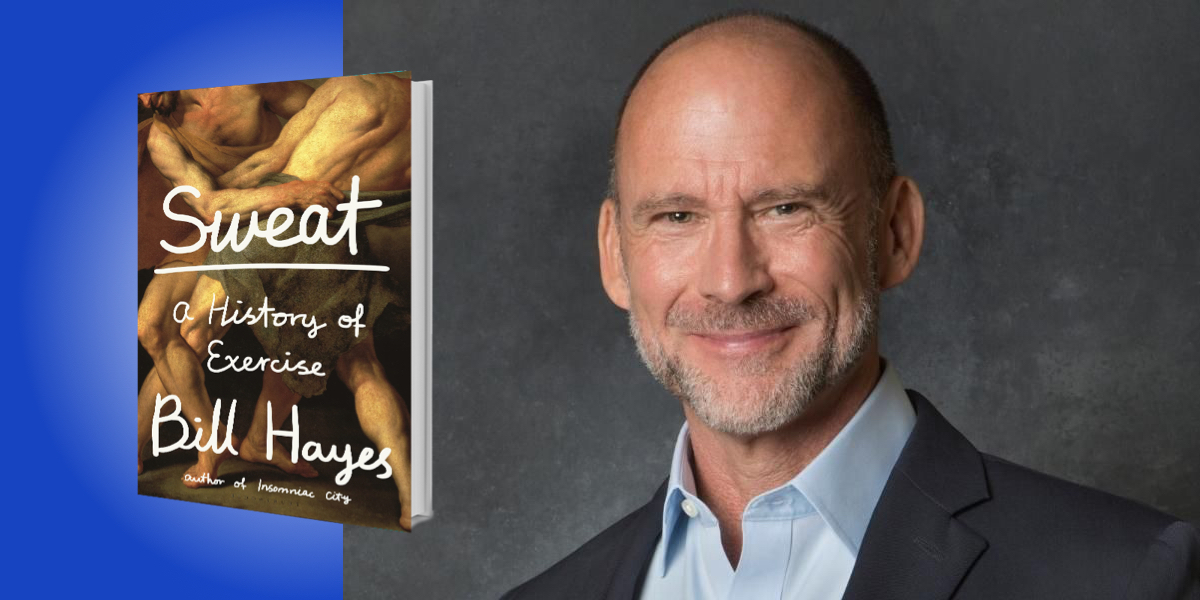

Bill Hayes is a journalist and photographer whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and the New York Review of Books. He’s also the author of seven books, and the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in nonfiction.

Below, Bill shares 5 key insights from his new book, Sweat: A History of Exercise. Listen to the audio version—read by Bill himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Exercise is not a modern phenomenon.

The very idea that exercise is good for you—that it improves your overall health and well-being—has been a presumption, even a truism, going back to ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt, and China. More than two millennia ago, the Indian physician known as Suśruta advocated exercise to maintain “equilibrium” in the body. In the Western world, an Athenian wrestler-turned-physician named Herodicus prescribed exercise to his patients. But it was one of his students, Hippocrates—now commonly known as the father of medicine—who fully articulated the tenets of exercise in the 5th century BCE. “Eating alone will not keep a man well; he must also take exercise,” Hippocrates stated, “for food and exercise, while possessing opposite qualities, yet work together to produce health.” Hippocrates is credited with writing two treatises on healthful living, covering diet, exercise, rest, and other matters. He emphasized that one must pay careful attention “to proportion exercise to bulk of food, to the constitution of the patient, to the age of the individual,” and so on. In other words, an exercise regimen must be customized to the person and, by definition, incorporated into daily life.

It is no stretch to say that our modern notion of a workout plan derived from these ancient sources.

2. Gyms and naked exercising were common in antiquity.

In ancient Greece and in the early Roman Empire, there was at least one gym in every town. The gym was as much a part of culture and society as the theater and marketplace, albeit a place where only upper-class men and boys were welcome. Women were not permitted into gyms, even just to watch.

“The word ‘gymnastics’ comes from the Greek term for ‘exercising in the nude,’ the standard practice in ancient Greece for hundreds of years.”

While it’s true that Plato (who, by the way, was a competitive wrestler) says in his treatise The Laws that “women, both young and old, should exercise together with the men,” it wasn’t until the 19th century when a whole confluence of events—the impact of the Industrial Revolution, for example, and the burgeoning women’s rights movement—made it possible, at long last, for women and girls to sweat, too.

Back in Plato’s day, gyms—also called palestras—were official buildings, owned by the city and maintained by a dedicated staff that included personal trainers and the ancient equivalent of towel boys. Private gyms existed, too, and for these, visitors paid membership fees, just as one does today. And where there were gym members, guess what? There were gym rats, too. The ancient Greek word for “gym rat” literally translates as “gym addict.”

One thing that was different back then—no gym clothes. People exercised naked. In fact, the word “gymnastics” comes from the Greek term for “exercising in the nude,” the standard practice in ancient Greece for hundreds of years.

3. Actual human sweat was once bought and sold.

The sweat of athletes was a prized commodity in the ancient world. After competing or simply exercising, athletes would scrape the accumulated sweat from their bodies and funnel it into small pots using a celery-stalk shaped metal tool, called a strigil, that was created expressly for this purpose. This presumably funky-smelling mixture, called gloios, was considered so precious that some went so far as to take scrapings from bathhouse walls where athletes had leaned and left sweat tracings from their bodies. Ancient Greek and Roman writers such as Pliny the Elder attested to this practice. Pliny reported that the masters of the gladiatorial schools sold such scrapings for the ancient equivalent of thousands of dollars.

“Athletic sweat wasn’t used, as one might guess, to enhance athletic performance. It was used to treat the most uncomfortable maladies on one’s most private parts: hemorrhoids and genital warts.”

Hard as this might be to believe, records of ancient business dealings confirm that this was true. Gloios provided a significant revenue stream for the Greek gyms at which it was sold—a needed supplement to membership fees at private gyms. It was used for medicinal purposes, the belief being that gloios must contain the essence of arete—the striving for excellence that defined a great athlete. But here’s the thing: athletic sweat wasn’t used, as one might guess, to enhance athletic performance. It was used to treat the most uncomfortable maladies on one’s most private parts: hemorrhoids and genital warts.

4. Christians disapproved of exercise.

The culture of exercise and athletics, so much a part of ancient Greek and Roman DNA, was essentially snuffed out with the rise of Christianity. The first Christian Roman emperor, Constantine the Great, banned gladiatorial contests in 325 CE. 70 years later, Theodosius I brought the Olympic Games to an end completely. This wasn’t simply because physical activity was antithetical to the tenets of Christianity. Athletic competition was linked to pagan rituals—like blood sacrifices of animals—and dedicated to the pantheon of Greek and Roman gods. This had a trickle-down effect on exercise itself. Cathedrals replaced gyms as sacred sites; it was the holy spirit—the soul—that was now to be glorified, not the body.

This transition didn’t happen overnight or with a single decree, but within a few hundred years, the notion of exercise for the sake of exercise was considered indecent—and definitely un-Christian. As Saint Bernard proclaimed in the 9th century: “The spirit flourishes more strongly and more actively in an infirm and weakly body.” This anti-exercise attitude did not change significantly until the Enlightenment of the 18th century, by which time there was a much better understanding of the human body. Later, Christianity and exercise would be coupled together, a leading example of this being the YMCA—Young Men’s Christian Association—which was established, with gyms, in the 19th century, and helped launch a worldwide movement called “Muscular Christianity.”

“Within a few hundred years, the notion of exercise for the sake of exercise was considered indecent—and definitely un-Christian.”

5. The proof didn’t come until the 1950s.

Surprisingly, indisputable scientific evidence for the benefits of exercise was not established until the early 1950s. One of the leading pioneers in this area was a British epidemiologist named Jeremy Morris, a man who, after his death at age 80 in 2009, was called by some obituary writers “the man who invented exercise.”

Although he trained as a medical doctor, Morris had become a clinical epidemiologist focused on public health. After World War II, one issue that emerged as a serious concern was a dramatic rise in coronary heart disease, the exact cause of which was unknown at the time. But Morris had a hunch that a person’s occupation might somehow be a factor. In what now seems like an ingenious idea, Morris designed a scientific study focusing solely on the drivers and conductors of double-decker buses, trams, and trolleys. For more than a year, he studied over 30,000 men. Although they worked in pairs in the same vehicle, their jobs were completely different: Drivers just sat and drove all day, whereas conductors hopped off and back on the tram or trolley constantly and, in the case of double-decker buses, up and down the stairs countless times during their shifts. For these men, work itself was a workout.

The results were unambiguous. In Morris’s paper on the study, first published in The Lancet in 1953, he concluded that the conductors had far less heart disease than the sedentary drivers, and it appeared in them at a later age. Morris felt that it was “the greater physical activity of ‘conducting’” that explained why these men remained healthier than their counterparts behind the wheel. His study helped establish a solid foundation for subsequent scientific research into exercise, paving the way for the fitness- and wellness-obsessed culture we live in today.

In retrospect, the ancients hadn’t been too far off. After all, nearly 2,000 years ago, the Roman physician Galen had defined exercise as “vigorous movement” that causes breathing to increase. And yet, Galen felt it certainly shouldn’t make you miserable: “In my opinion,” he stated, “the best exercises of all are those which are able not only to exert the body, but also delight the soul.”

To listen to the audio version read by author Bill Hayes, download the Next Big Idea App today: