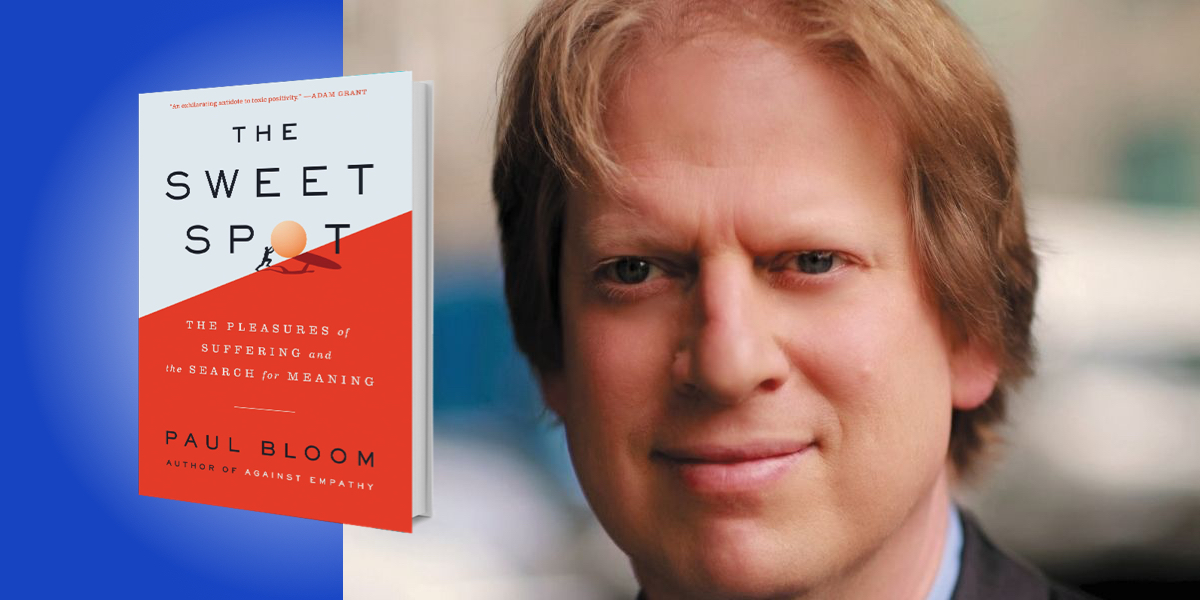

Paul Bloom is a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto and a professor emeritus at Yale. The author of six books, his writing has appeared in Nature, Science, The Guardian, The New Yorker, and The Atlantic.

Below, Paul shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Sweet Spot: The Pleasures of Suffering and the Search for Meaning. Listen to the audio version—read by Paul himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. “He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.”

A lot of people will tell you that humans are hedonists. We just want to have a good time—we seek out pleasure, we avoid pain, and that’s the end of it. Sometimes we choose to suffer, but under this view, the only reason we do that is to get what we want. We go to work to make money to have fun. We go to the store to buy food to eat. But in the end, all we really want is pleasure.

But I don’t think that’s right, and I hope my book will convince you to take seriously an alternative, which we could call motivational pluralism. It’s a terrible-sounding name, but the idea is that we want many things. We should reject one-word answers to the question, “What motivates people?” It’s nicely summed up by the economist Tyler Cowen, who writes, “What’s good about an individual human life can’t be boiled down to any single value. It’s not all about beauty or all about justice or all about happiness. Pluralist theories are more plausible. Postulating a variety of relevant values, including human well-being, justice, fairness, beauty, the artistic peaks of human achievement, the quality of mercy and the many different, and indeed, sometimes contrasting kinds of happiness. Life is complicated.”

Now, one alternative to pleasure is meaning. This drive for meaning is every bit as important as the drive to have a good time, to enjoy ourselves, to be happy. I present a lot of scientific data for this position in my book, but it’s an old idea, which is why I draw upon the writings of Viktor Frankl, particularly his book Man’s Search for Meaning.

“Those who had the best chance of survival were those whose lives had broader purpose, who had some goal or project or relationship, some reason to live.”

In the 1930s, Frankl, who was a psychiatrist in Austria, ended up in Nazi concentration camps—first at Auschwitz, and then Dachau. Even in the camps, he continued his work. His topic of research was depression and suicide, and he studied his fellow prisoners, wondering about what distinguished those who maintained a positive attitude from those who couldn’t bear it and lost all motivation, often killing themselves. He concluded that the answer is meaning. Those who had the best chance of survival were those whose lives had broader purpose, who had some goal or project or relationship, some reason to live. Frankl was fond of quoting Nietzsche, “He who has a why to live can bear almost any how”—a nice illustration of the complexity and richness of human motivation.

2. Suffering can enhance pleasure.

I started this book because I was interested in a puzzle. Normally, we avoid pain, anxiety, stress, and discomfort—but sometimes we seek it out. Think of your own favorite negative experience. Maybe you go to movies that make you cry or scream or gag. You might listen to sad songs. You might poke at sores, eat spicy foods, immerse yourself in hot baths or saunas. Maybe you climb mountains, run marathons, decide to get punched in the face in gyms and dojos. Why would you seek out these unpleasant experiences? One reason is what Paul Rosin calls benign masochism. Sometimes pain can help you escape from yourself. A sharp jolt of pain can distract you from your day-to-day worries. Sometimes we seek out pain to signal to others how tough we are. Sometimes pain is a source of flow and mastery. C. S. Lewis points out that if you’re not eating because you have no food, there’s not much good to be said about that, but if you’re not eating because you’re fasting, that could be a demonstration of control and mastery.

Probably the simplest explanation for benign masochism is that pain and pleasure are intertwined. Neuroscientists will tell you that the brain is a difference machine; experience is understood in terms of contrast. In studies involving gambling, losing $10 is pretty bad, but if you thought you’d lose $50, it’s not bad at all. It’s actually quite positive.

We play with this contrast in order to give ourselves pleasure. We seek out pain to maximize the contrast with the experience that comes next. The bite of a hot bath could be worth it because of the blissful contentment that comes when the temperature cools. The burn of hot curry can be pleasurable if it’s followed by the shocking relief of a cold beer. This is the contrast theory of why we choose to experience pain. It’s like the old joke my dad used to tell me about the guy who was banging his head against the wall. When asked why he said, “It feels so good when I stop.”

“We seek out pain to maximize the contrast with the experience that comes next.”

3. Suffering can give us meaning.

Young men sometimes choose to go to war, and while they don’t wish to be maimed or killed, they hope to experience challenge, fear, and struggle. Some of us choose to have children. We usually have some sense of how hard it will be, but we rarely regret our choices. More generally, the projects that are most central to our lives involve suffering and sacrifice. If they were easy, what would be the point?

Five facts link suffering and meaning. First, individuals who say their lives are meaningful tend to report more anxiety, worry, and struggle than people who say their lives are happy. Second, the countries whose citizens report the most meaning—that is, they say they live the most meaningful lives—tend to be poor countries where life is relatively difficult, and this is different from the happiest countries, which tend to be prosperous and safe. Third, the jobs that people say are the most meaningful, such as being a medical professional or member of the clergy, often involve dealing with other people’s pain. Fourth, when asked to describe the most meaningful experiences of our lives, we tend to think about extremes; this includes very pleasant events, but also very painful events. Finally—and I think most importantly—we often choose pursuits we know will test us, everything from training for a marathon to raising children, because we know, at a gut level, that these pursuits matter. As the novelist Julian Barnes put it, “It hurts as much as it’s worth.”

4. Effort sweetens life.

Psychologists like to talk about the effort paradox. We normally seek to reduce effort, and try to make things easy for ourselves. But sometimes effort is the secret sauce that makes things better. One of the classic findings in psychology is that the more effort you put into something, the more you value it. This is the logic of Benjamin Franklin’s classic advice on how to turn a rival into a friend: Ask him or her to do you a favor. Having worked to help you, they’ll like you more. Or take Mark Twain’s story of when Tom Sawyer had to whitewash his fence. When Tom’s friends come by, he pretends to be delighted at the task, and soon his friends end up paying him for the privilege of working on the fence. As Twain puts it, “Tom Sawyer had discovered a great law of human action, namely that in order to make a man or a boy covet a thing, it is only necessary to make that thing difficult to attain.”

“People prefer objects that they helped create. They became especially attached to it, and the more work, the better.”

Now those are anecdotes and stories, but there’s laboratory support for this. Michael Norton and his colleagues at Harvard Business School did a series of experiments where they found that people prefer objects that they helped create. They became especially attached to it, and the more work, the better. They call this the IKEA effect, after the big-box store where people assemble their own furniture and seem to value it more.

Another manifestation of the pleasures of effort is what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls flow. You might think that the perfect life is sitting on the sofa, watching Netflix, and relaxing. But Csikszentmihalyi discovered that people actually get enormous amounts of pleasure, satisfaction, and richness when they’re immersed in an activity. You know you’re in flow when time goes by, yet you don’t notice it. You forget to eat, and miss appointments. For this to happen, though, the activity has to hit a certain sweet spot. If it’s too easy, you’ll get bored. If it’s too difficult, you’ll get anxious. But the power of flow, which is experienced by great athletes, by musicians, by writers, and at times by all of us, is a nice illustration of the centrality of effort in human satisfaction.

5. Don’t try to be happy.

There are two reasons for this. The first is that it’s self-defeating; you can screw up being happy by trying too hard. There are studies that look at the extent to which people are motivated to pursue happiness. They might ask people questions like, “To what extent do you agree with the statement, ‘Feeling happy is extremely important to me,’ or ‘How happy I am at a given moment says a lot about how worthwhile my life is’?” It turns out that people who agree with those items are more likely to be depressed and lonely. There are a few reasons for this. By setting unrealistically high expectations for themselves, people who pursue happiness set themselves up for failure—or maybe the self-conscious pursuit of happiness makes you think a lot about how happy you are, and that gets in the way of being happy. It’s like how thinking about how good you are at kissing probably gets in the way of being a good kisser.

The second part of the problem is that when we are asked what makes us happy, we’re usually wrong. It turns out that pursuing extrinsic goals—that is, goals related to praise and reward, like looking good and making money—makes you less happy, less fulfilled, and is linked to depression, anxiety, and mental illness. Somewhat paradoxically, if you want to be satisfied with your life, if you want to experience pleasure and joy and meaning, you may need to try less hard at attaining these things.

To listen to the audio version read by author Paul Bloom, download the Next Big Idea App today: