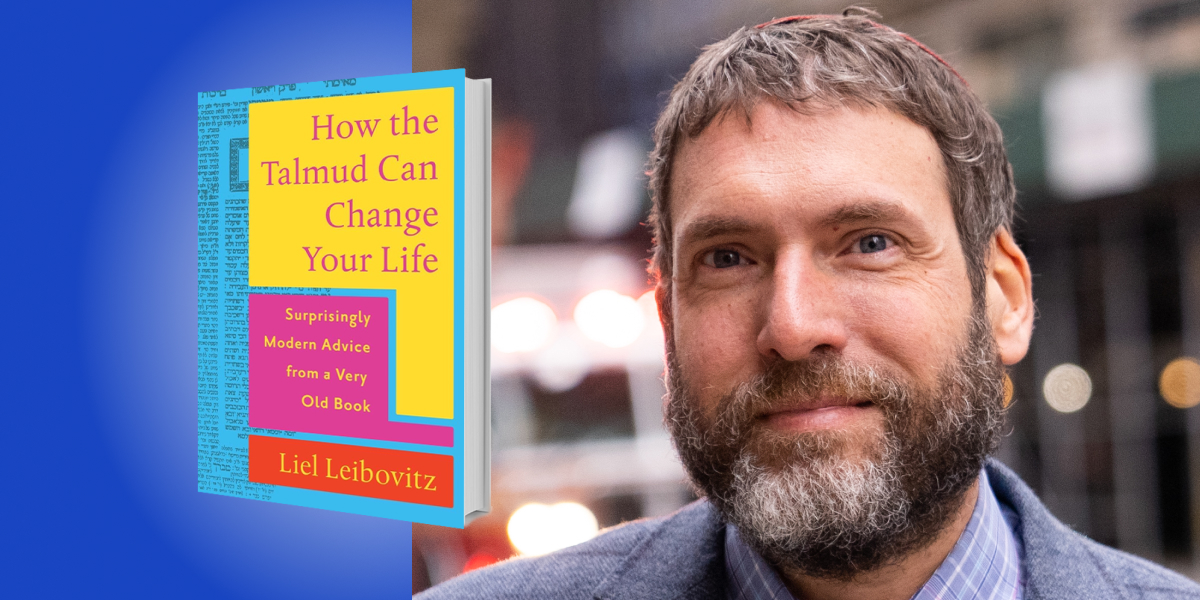

Liel Leibovitz is a podcast host and author. He is cohost of Unorthodox, a popular Jewish podcast, as well as Tablet’s daily Talmud podcast Take One.

Below, Liel shares five key insights from his new book, How the Talmud Can Change Your Life: Surprisingly Modern Advice from a Very Old Book. Listen to the audio version—read by Liel himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. It’s never too late to do the right thing.

There’s always, always, always hope for redemption. You might have squandered every opportunity you ever got, you might have hurt the ones you love, you might have made one bad life decision after another, but as long as you can see the error of your ways and summon just one moment of pure intention, of real remorse, of genuine dedication to doing better, you will be forgiven and rewarded with your happily ever after.

The Talmud is chock-full of such tales of late bloomers, none more famous than its absolute greatest hero, a gentleman by the name of Rabbi Akiva. Akiva is mentioned in the Talmud 1,341 times, far more than any other sage. Yet, unlike any other epic hero, we know almost nothing about his early life. Why? Well, because this GOAT—greatest of all time—was an illiterate goat shepherd until he was forty. One day, Rachel, the beautiful young daughter of his rich and mean boss, sees Akiva and is moved by how kind and lovely he is to his animals. She agrees to marry him on the condition that he goes back to school and becomes a scholar. Her father, of course, throws a fit, disowning the poor Rachel, but she doesn’t care. She lives in a barn with her husband, and their love is more precious to her than all the luxuries of her childhood home. Then, Akiva leaves. He spends 14 years away, not only learning Torah—the Five Books of Moses—but becoming by far the most famous and celebrated scholar of his day. When he returns, he is surrounded by tens of thousands of followers, like a second-century rock star, and some of these groupies push Rachel aside as she runs to greet her husband. “Stop,” Akiva tells them, “everything that I have or that you have truly is hers.”

It’s a romantic story, but its lesson is unmistakable: You can be middle-aged, broke, and illiterate, but if you believe in yourself, and if you are lucky enough to have someone who loves you and believes in you, you can still turn it all around. It’s never too late.

By now, all this talk of rabbis and learning is probably making you think that the Talmud advocates a life of monkish abstinence from everything that’s beautiful and enjoyable. That, hallelujah, couldn’t be further from the truth.

2. Fun is holy.

Faith, the rabbis understood, can be tricky. Spend too much of your time thinking about God and heaven and a bunch of other concepts so big and otherworldly you couldn’t possibly understand them, and, well, you’ll miss out on a lot of the great pleasure of just being alive, right now and right here, on earth. Enjoying life, they argued, is very much the point; why else would the Almighty create this amazing planet if not for us to enjoy every wonderful thing it has to offer?

To that end, they perfected the concept of Hiddur Mitzvah, which, loosely translated, means that everything that you are commanded to do, you should do in the most stylish, pleasurable, and wonderful way you could possibly afford.

“We should live every day as if it’s a special occasion.”

This idea eventually led to a fight between two of the Talmud’s greatest frenemies, the ancient sages Hillel and Shammai, who both lived around the time of Jesus’s birth. Shammai was the hard-core one, a stickler for the rules, and he wanted to make sure he celebrated the Sabbath in the most spectacular fashion possible. So, he would spend every day of the week looking for special things—meat, treats, and other delicacies—to buy and save for Friday night, just so, come the Sabbath, he may have the most festive feast in town.

His pal, Hillel, the more lenient one, was having none of it. Sure, he said, the Sabbath is holy, but so is every minute of our very short stay here on earth, so rather than walking around and saving all the best stuff for a special occasion, he taught us, we should live every day as if it’s a special occasion. And we should treat ourselves to the best things our money can buy, not because we’re shallow or materialistic or care only about accumulating more stuff. We should do so because being surrounded by nice things—treating ourselves to a nice bag, say, or enjoying a great bottle of wine with a lovely dinner—better prepares both our bodies and our souls for their ultimate job, which is being mindful of and grateful for all the wonders that were created just for our pleasure.

But Hillel didn’t just stop there. He had other ideas, ideas of a more scatological nature.

3. If you can’t poop, you can’t pray.

Hillel, as I mentioned before, was a very big deal. You may recognize him from his very famous saying—”that which is hateful to you, do not do unto others.” Naturally, he had a lot of students who spent every day observing and admiring their great teacher. One day, the Talmud tells us, Hillel got up in the middle of a lesson and announced that he was going to perform a great mitzvah, or righteous deed. This excited the students! What great deed was the famous rabbi going to do? What priceless lesson will he teach? Without saying a word, Hillel got up, and… went to the bathroom. The students, stunned, stood outside the door, listening as their teacher relieved himself. And when he came out, they were confused and maybe even a little bit mad.

“Rabbi,” they asked, peeved, “was this really a righteous deed you just did?”

“Yes,” Hillel answered, “because otherwise, my body would break down.”

He wasn’t being cute. He was teaching his students a key philosophical lesson. There’s no two of us—our mind and our body. We’re one beautiful, holistic, flawed, amazing, disgusting, and absolutely sacred creation, and there’s no way for us to separate our basest appetites from our loftiest aspirations. If we can’t poop, we can’t pray, which makes both actions holy and wholly worthy of our consideration.

How should we approach our actions, then? Is there some organizing principle for going through life? Yes, say the rabbis.

4. Don’t Netflix and chill.

The rabbis of the Talmud obviously didn’t have Netflix, and, from what we know about them, chilling wasn’t their strong suit, either. But they begin the Talmud with the following teaching: Jews, they remind us, are required to pray three times a day, morning, noon, and night. And even though the evening prayer can technically be recited at any point until the dawn of the following day, you should absolutely do it before the clock strikes midnight. Why?

Well, say the rabbis, imagine the following scenario: It’s late afternoon. You come home from work. You’re dead tired because it’s been a heck of a day at the office. So, you grab a bite to eat, maybe a glass of wine to take the edge off. You play with the kids, talk to your spouse, and then tell yourself, “I’ll just sit on this couch for a minute.” Which is what so many of us moderns do when we Netflix and chill. Then, the rabbis continue, next thing you know, you wake up, startled, to discover that you’ve fallen asleep, and now it’s already morning and you’ve missed your chance to pray.

“Block off at least 10 minutes every day—same time each day, please!—for something that you find immensely important.”

If there’s something that’s really important to you, the rabbis teach us, you have to make time for it. Don’t say, “I’ll do it later.” Don’t leave it to chance. Make it a priority. Schedule a specific time to do it, and do it before you do anything else. It’s a life hack as easy as it is profound: Switch on your Google calendar, or paper day planner, or whatever else you use, and block off at least 10 minutes every day—same time each day, please!—for something that you find immensely important. I, of course, recommend Talmud study, but it can be meditation, time with a loved one, or anything else that moves you, nurtures you, and reminds you of what truly matters in life. The key is to make time rather than let time take you over.

That all is very nice, but we’re human beings, and when we do things, we don’t like to do them alone. We’re social creatures, which means we need friends. But how should we go about making friends?

5. Buy yourself some friends.

It sounds weird, right? Our entire lives, we’re taught that friendship is this ephemeral thing, that we gravitate to our friends as if by magic because we both like the same things or dislike the same things or share some other strange, almost mystical, bond. Nah, say the rabbis: In Pirkei Avot, the part of the Talmud that deals with ethics, they tell us very explicitly: if you want a friend, you’re going to have to buy yourself that friend.

What do they mean? They’re not suggesting, of course, that you should go around handing out ten-dollar bills hoping that folks would take a liking to you. Instead, they’re reminding us of something so many of us busy, hurried moderns tend to forget: friendship is work. It doesn’t just happen. It requires effort. It is, put crudely, an investment.

Did you bother calling your friend today, knowing she had an unpleasant doctor’s appointment earlier? Did you take some time off your crazy, hectic schedule to go hang out with your friend because he sounded a little bit down? Did you see something nice you thought your friend would like and then went ahead and bought it as a gift, just to be sweet and thoughtful? Because the rabbis think you should do all of the above and then some. They chose the crassest metaphor available to them—that of making a purchase—to remind you that unless you’re paying—with your time, with your attention, with your cash—you’re not really rockin’ this whole friendship thing right.

To listen to the audio version read by author Liel Leibovitz, download the Next Big Idea App today: