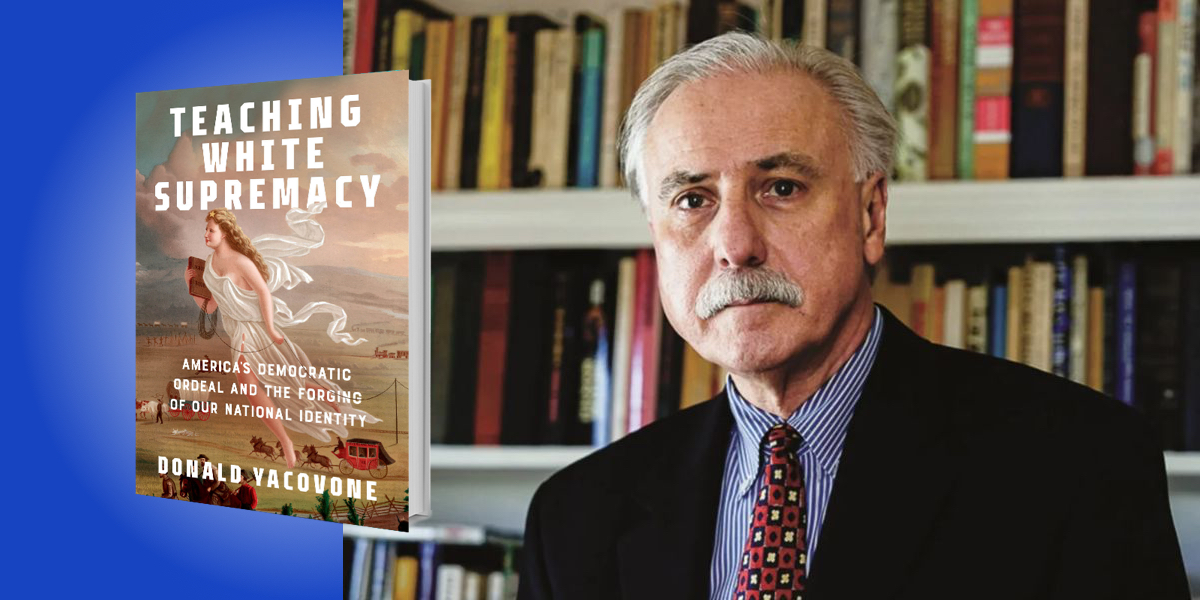

Donald Yacovone is an associate at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University. He has spent has career studying the antislavery movement, the African American role in the Civil War, and race and gender in American history. In 2013, he received the W.E.B. Du Bois medal, Harvard’s highest honor in the field of African American studies. Teaching White Supremacy is his ninth book.

Below, Donald shares 5 key insights from his new book, Teaching White Supremacy: America’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our National Identity. Listen to the audio version—read by Donald himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Understanding our current crisis.

Far too many Americans, as the famed author and critic James Baldwin explained in The Fire Next Time, remain “trapped” in a past “which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.” We have underestimated the challenge of releasing Americans from their past because, as Baldwin emphasized, “the danger, in the minds of most white Americans is the loss of their identity.”

This is the underlying issue confronting society today, the submerged tectonic plate that is now cracking, and perceived as being washed away by demographics and “liberalism.” To many it is a terrifying loss of the known universe, an attack, as Baldwin wrote, on “one’s sense of one’s own reality.”

2. White identity has been fused to American identity.

Responsibility for a popular consciousness of exclusion, an enduring identity of true Americans as only descendants of white Europeans, rests broadly and profoundly in our history. The principles of white supremacy predate the American republic and ironically helped shape the commitment to democratic republicanism and national identity that later emerged.

“The understanding of African Americans as a people who exist outside of mainstream white consciousness and identity remains painfully with us.”

As the legendary 17th century judge of the Salem Witchcraft trials, Samuel Sewall explained, African Americans “still remain in our Body Politick as a kind of extravasat Blood,” that is blood existing outside of society’s regular veins and capillaries. Although an antislavery advocate, Sewall remained forever unnerved by the mere presence of Africans in New England, harboring fear that people would not retain their cherished whiteness “after the resurrection.”

The understanding of African Americans as a people who exist outside of mainstream white consciousness and identity remains painfully with us.

3. A Northern, not a Southern creation.

Most Americans understand the persistence of “racism” as the legacy of Southern slavery. But the ideology of slavery is only a subset of the larger, more enduring, and specifically Northern ideology of white supremacy. From the earliest colonial days to the full blossoming of white supremacy in the nineteenth century, Northern thinking has propelled racial subordination—so not just defenders of slavery and Southern resistance to the Civil Rights Movement.

In every important field of thought and culture—literature, religion, science, law, education—it has been Northerners (especially from New England and New York) who have most aggressively suppressed African Americans and created the ideology of “white supremacy.” Any hope for national unification today depends upon recognition of collective responsibility.

4. The most dangerous tool, with the greatest influence.

History textbooks have been the “prayer-books” of our national civil religion, engines of democracy and equality. By design, they contain our national aspirations, proud legacy, and professed ideals. But we have been selective in what we cherish within them and blind to what, has proven disconcerting, if not shameful and humiliating.

“Most textbooks, and certainly those appearing since the beginning of the twentieth century, presented African Americans as a foreign, unwanted presence, a necessary evil, or a threat.”

Textbooks acted as syringes, injecting cultural poison into the brains of generations of students. The very first page of one 1930 textbook shrieked: “THE STORY OF THE WHITE MAN.” In 1939, the NAACP surveyed popular American history textbooks and revealed that textbooks “drilled” white supremacy into children’s minds. One could see plainly “how hate and disgust is motivated against the American Negro.” Most textbooks, and certainly those appearing since the beginning of the twentieth century, presented African Americans as a foreign, unwanted presence, a necessary evil, or a threat, and always as one 1914 textbook asserted, “a problem that it took many years to solve.”

5. What we have been teaching.

Before the 1960s, schoolbooks presented the institution of slavery as the white man’s burden, a responsibility to “save” the African from barbarism and despair. It appeared as a benevolent institution, little more than a series of picnics, barbecues, singing, and dancing. Slaves rarely fretted over their lives and often felt “deeply devoted to their master and his family,” and in return “white children loved their mammies.” Heaven, to the “Negro,” was a place of rest from all labor, “the fitting reward of a servant who obeyed his master and loved the Lord.”

Such history, what one parent labeled “curricular violence,” has been pounded into the consciousness of generations of students. Even when modern schoolbooks offer the actual history of the institution, teachers either avoid it due to lack of training or from fear of losing their job. As modern commentators have observed, despite a ghastly war fought over slavery and over 150 years of concerted efforts by civil rights activists, “the notion of America as white and Christian has stubbornly refused to dissipate.” The soul of the nation remains white.

To listen to the audio version read by author Donald Yacovone, download the Next Big Idea App today: