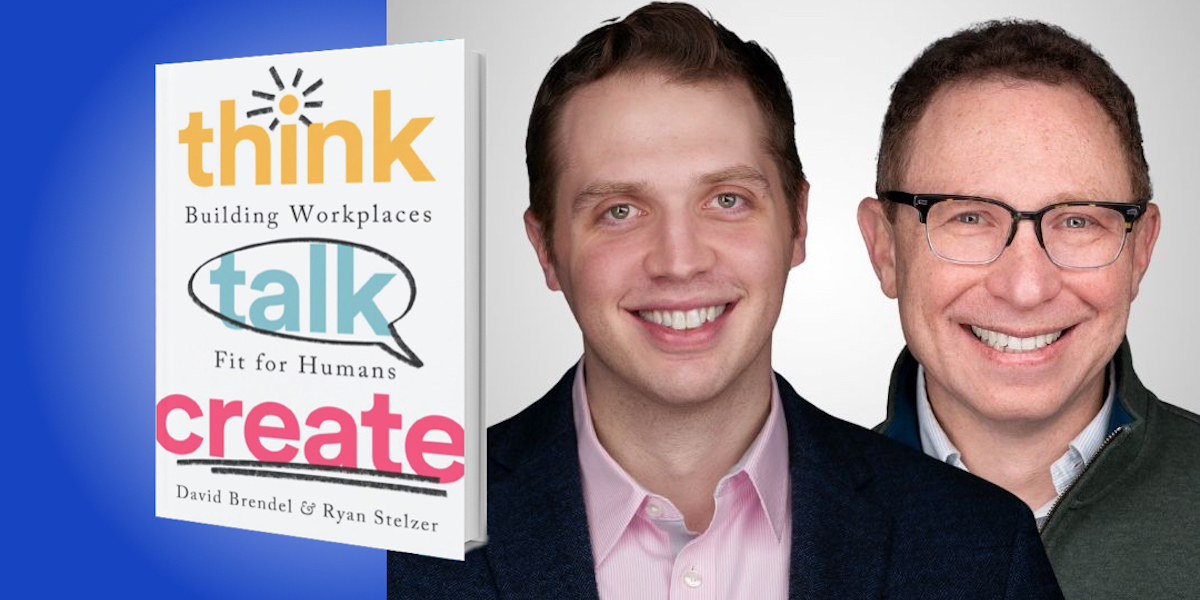

David Brendel is the co-founder of Strategy of Mind, an executive coaching, consulting, and leadership development firm rooted in philosophy and psychology. He is a board-certified psychiatrist with an MD from Harvard Medical School and a PhD in philosophy from the University of Chicago. Ryan Stelzer is co-founder of Strategy of Mind. He served in the Obama White House as a presidential management fellow, where his team was responsible for improving and sustaining high levels of performance across federal agencies.

Below, David and Ryan share 5 key insights from their new book, Think Talk Create: Building Workplaces Fit for Humans. Listen to the audio version—read by David and Ryan themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The CEO should be a custodian.

A few years ago, we ran a half-day workshop for a property management company that ran assisted living facilities. They were struggling with low morale, high employee turnover, and a plateau in their earnings. In a large catering hall, we arranged for the members of each division of the company to sit together at round tables. After a mini-lecture, we pivoted to our favorite open-ended question: “What keeps you up at night?” At first, we heard a bunch of common workplace grievances: heavy workloads, too many emails, a lack of communication from leadership.

At the last table to go sat the custodians. Their designated summarizer reported that what kept them up at night was loss. These custodians didn’t just fix leaky faucets—they also became friends and confidants. With tears in his eyes, the custodian told a story about how an elderly resident called him regularly to open a pickle jar that she was too weak to open herself. They would then sit together and warmly talk about each other’s families. They came to care about each other over a number of years. And when the calls to help with the pickle jar ceased, he was devastated.

“The path to psychological safety and high performance runs through open-ended questions.”

The floodgates then opened across the room, as participants dove into energized discussions about reconnecting with the company’s core human values. Months later, we learned that many of their relevant metrics had improved significantly: higher employee engagement scores, less turnover, greater quarterly earnings. They attributed the turnaround in large measure to the workshop. An open-ended question—”What keeps you up at night?”—had transformed things.

This company’s experience reflected the findings of Google’s Project Aristotle study. Google learned a few years earlier that the thing which best distinguished its highest-performing teams was the “psychological safety” people experience when they are free to brainstorm and speak openly, without fear of negative judgment or reprisal. The path to psychological safety and high performance runs through open-ended questions. One such question revealed that custodians may be the most reliable stewards of an entire corporate enterprise.

2. Conversation is a hard science.

Ensuring that custodians contribute to overall company growth shouldn’t be serendipitous; it’s best to be proactive and intentional about fostering great conversations with everyone at work. Those conversations should start with carefully constructed open-ended questions, which is harder to do than it might appear—especially when we’re overwhelmed by our to-do list. But we should be as rigorous with how we talk to each other as we are with the more technical aspects of our jobs.

Recent research shows that the vast majority of conversations wind down and end with one or both people feeling dissatisfied. We live in a world where people seem more interested in barking orders or expressing opinions than in curiously asking questions, genuinely listening to the replies, and having enough self-restraint to foster an exchange of ideas. The problem occurs everywhere we look, from the workplace to the kitchen table to the halls of government power.

“People seem more interested in barking orders or expressing opinions than in curiously asking questions, genuinely listening to the replies, and having enough self-restraint to foster an exchange of ideas.”

Other research shows that infants experience significant development of Broca’s area, the brain region responsible for expressive language, when adults talk with them rather than talk to them. Good parents know this intuitively, and engage continually in linguistic back-and-forth that promotes healthy development. Adults reap similar benefits, as we know from Project Aristotle and related studies. But fostering psychological safety is no easy task; it requires a disciplined methodology to be effective and sustainable.

The methodology we’ve developed, which we call “active inquiry,” can be fine-tuned through practice. It entails a meticulous and nearly exclusive focus on asking open-ended questions and making clarifying statements. Active inquiry breeds neural synchrony and interpersonal harmonization. It gives people the space to slow down, reflect on pesky problems, and construct novel solutions. Closed-ended questions (which result in little more than yes/no responses) and leading questions (where the inquirer already thinks they know the right answer) do just the opposite.

3. Humanism is an overlooked technology.

Active inquiry is a key skill not just in business, but in all areas of professional practice, including medicine. Physicians are trained to deploy their wealth of scientific knowledge to render a diagnosis and make a treatment plan. But without active inquiry as part of their skill set, opportunities for treatment may be lost. Sociologist Thorstein Veblen talked about the “trained incapacity” of experts—the blind spots created when outsize knowledge in one area obstructs the view of other salient human phenomena.

Dr. C. Miller Fisher was a pioneer of the field of neurology and an expert on abulia, a syndrome of apathy and absence of spontaneous speech in patients with a stroke in a particular brain region. Fisher held a weekly case conference for Harvard Medical students working on the neurology ward at Massachusetts General Hospital in the 1990s. At one of these conferences, Fisher sat face-to-face for two hours with a middle-aged man with abulia. On the wall behind Fisher was a majestic painted portrait of the great doctor. And indeed, the patient hardly said a word and his facial expression was totally flat.

“Active inquiry is a key skill not just in business, but in all areas of professional practice.”

But Fisher missed something important. After the conference ended, a medical student pushed the patient’s wheelchair into the hallway. The student then paused, came around to the patient’s side, and kneeled down to be at eye level with the patient. He then kindly asked an open-ended question: “How was the conference for you?” In response to the active inquiry, the patient’s face brightened, and he blurted out, “That was quite a portrait of Dr. Fisher!”

The patient gradually improved in the coming days to the point that he could return home. Indeed, something remarkably therapeutic happened for a patient whose abulia turned out to be much more complex than even a preeminent expert in clinical neurology could understand.

4. It pays to be raised in a barn.

Professional hockey is a surprisingly good place to glimpse the power of active inquiry. Starting in 1972, the New York Islanders played in a beloved arena that, by the early 2000s, was pretty dilapidated and malodorous. Fans affectionately began to call it the “Old Barn.” But the team was raised there, starting as a hapless and underfunded team and later winning the Stanley Cup championship 4 times in a row. The Islanders were woven into the fabric of Long Island, adored by its middle-class families living in the backyard of the world’s capital of finance.

That is, until the NHL and team owners saw greater financial opportunity in the swanky Barclays Center in Brooklyn. The team was moved there in 2016, and it was quickly a calamity, in part because it was so far away from the fan base. Ticket sales and revenue plummeted.

So the new team owners began to ask a masterful set of open-ended questions. Jon Ledecky joined fans on the Long Island Rail Road to and from games in Brooklyn, and he asked them what the team should look like in the future. They gave him an earful, and he took it all in with a warm, boyish smile. Ledecky also engaged with the governor, the Nassau County executive, and other stakeholders to fashion a new deal for his loyal customers on the Island.

“Perhaps a marriage of big bank and Old Barn values may be just what we need to bring the world of professional sports, and of the entire economy, into a more sustainably human equilibrium.”

As a result, the Islanders are moving into a new arena close to their fan base on Long Island. UBS, the multinational Swiss bank, has purchased the naming rights to the arena. The bank’s leaders would do well to conduct active inquiry sessions with residents across Long Island about how they can engage the community and excite the fan base. Perhaps a marriage of big bank and Old Barn values may be just what we need to bring the world of professional sports, and of the entire economy, into a more sustainably human equilibrium.

5. Believe yourself capable.

Urban legend tells of a story in which the famed psychologist William James was asked to deliver a lengthy speech in front of a crowd of academics and researchers. Settled in for an extensive report, the crowd was shocked by James’s choice to speak for just a few seconds. “They’ve asked me to talk about the last hundred years of psychological research,” he allegedly told them. “It can be summed up in this statement: People, by and large, become what they think of themselves. Thank you and good night.”

James’ notion is backed up by cognitive psychology research, that we can (and must) choose what we think and how to live. Each of us—regardless of our status at work or station in life—can make meaningful choices with outsize influence. We all need to use our choice and agency to ask good questions and promote psychological safety. You don’t have to be the CEO to make a profound difference; we all have agency.

“‘I am capable of changing the world,’” James said, “can only be true—or become true—if you first adopt the belief without prior evidence.” In other words, if you haven’t changed the world yet, the first step in doing so is believing that you can.

To listen to the audio version read by co-authors David Brendel and Ryan Stelzer, download the Next Big Idea App today: