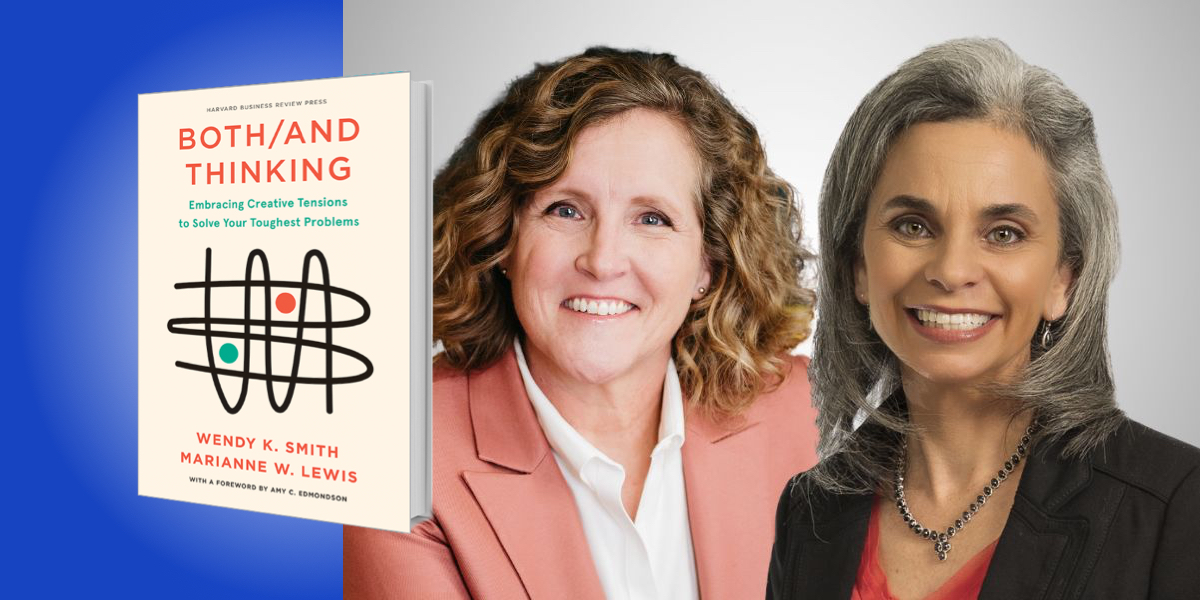

Wendy Smith is a professor of management and faculty director at the Women’s Leadership Initiative at the University of Delaware. Marianne Lewis is the dean of Carl H. Lindner College of Business at the University of Cincinnati, prior to which she was the dean of the Cass Business School in London, England.

Below, Wendy and Marianne share 5 key insights from their new book, Both/And Thinking: Embracing Creative Tensions to Solve Your Toughest Problems. Listen to the audio version—read by Wendy and Marianne themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Either/Or thinking jeopardizes problem solving.

We all face dilemmas that feel like a tug-of-war—whether in parenting or partnering, politics or leadership. These tensions lure us into either/or thinking. We want to make a clear decision—a tradeoff—to reduce ambiguity and uncertainty. To be fair, making tradeoffs can be useful, but over time, either/or thinking is limiting at best and detrimental at worst. This kind of thinking can lead to vicious cycles, which can follow three patterns: intensification, over-correction, and polarization.

First, focusing on one side of a dilemma can mean losing sight of the other. We describe this as falling down a rabbit hole. It might be fine to focus on one side for a while, but as time goes on, we get stuck. When situations change, we find that we can’t. The product design firms that I studied could survive by focusing on existing products, but when technology shifts, if they haven’t kept up with innovations, they get left behind. This pattern is called intensification.

Second, when stuck in a rabbit hole, we often swing wildly to the other side when we try to change. If you’ve ever been on a diet, you know this yo-yo between excessive discipline and excessive indulgence. This pattern is called over-correction. These swings act like wrecking balls—demolishing the good of the existing side along with the bad.

Finally, groups, teams, and organizations trigger the third pattern: polarization. This pattern defines our current political landscape, seeping into personal lives to strain families and friendships. Polarization occurs when groups make either/or decisions, picking and defending one side of an issue, diminishing, and eventually dehumanizing, the other. We use the metaphor of trench warfare because each group digs deeper into their own trench while firing at the opposition. Instead of creative problem-solving, we end up with casualties.

2. Both/and thinking enables creative, sustainable solutions.

Valuing opposing sides and seeking connections between them opens up creative and sustainable options. Consider Einstein’s theory of relativity. He developed this idea by trying to figure out how an object could be at motion and at rest at the same time. Or consider Paul Polman, CEO of packaged goods company Unilever from 2008-2018. He used both/and thinking to craft the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan, doubling the company’s profits while reducing its environmental footprint.

“Only recently has society started to think more broadly about paradox as the foundation of personal, organizational, and global challenges.”

Understanding the value of both/and thinking begins by understanding paradoxes. Paradoxes are the interdependent oppositions that lurk beneath dilemmas and persist over time. These yin-yangs underly so many of our personal and societal dilemmas: today-tomorrow, self-other, give-take, intrinsic-extrinsic motivation.

Greek philosophers learned from paradoxes over 2,500 years ago. On the other side of the world, Confucious and Lao Tsu claimed that the world rests on the ongoing interaction of these ebbs and flows. Over the past 100 years, brilliant physicists such as Niels Bohr, Michael Faraday, and others applied these ideas to the physical world. Quantum physics rests on assumptions of particles that are waves and points, are in movement and at rest, that exist and don’t exist. Similarly, psychoanalysts such as Carl Jung and Viktor Frankl point to paradoxes as the foundation of the human psyche. Only recently has society started to think more broadly about paradox as the foundation of personal, organizational, and global challenges.

Both/and thinking invites us to approach dilemmas by embracing paradoxes.

3. Start by changing the question.

We usually frame dilemmas as tradeoffs. On the top of a mountain while in college, I (Wendy) asked an either/or question: Should I study and teach ideas as an academic or use those ideas to have impact as a leader and consultant? Rather than wait for divine intervention as I looked out on the landscape, I could have flipped a coin. In time, I came to ask a different question: How can I study and teach ideas to have a positive impact on people’s lives? A whole new world of answers started to emerge.

Albert Rothenberg, a psychiatrist at Harvard Medical School, studied the diaries and writings of geniuses like Einstein, Pablo Picasso, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Virginia Woolf. He wanted to understand the inspiration behind their great ideas. They all changed the question. Their genius ideas emerged when they asked how they could bring together opposing forces.

Research shows that you don’t need to be a genius for new ideas to emerge. In one study, groups of students developed more creative objects when they were told to find ways for the object to be both novel and useful, compared with students who were told that novelty and usefulness contradict and that they should focus on one or the other.

“Their genius ideas emerged when they asked how they could bring together opposing forces.”

Imagine changing the questions asked regarding political issues. Often even everyday conversations sound like candidates arguing their cases. What if we stopped arguing over who is right and instead we assumed that people with different political views have valid and values-based perspectives? What if instead of defending our perspective, we ask them to share their experiences and understandings, and see what we can learn?

4. Find mules and try tightrope walking.

We need a set of tools for sustaining patterns of both/and thinking. These tools include practices like separating and connecting—pulling apart opposing views or competing demands to understand each, then looking for the synergies between them. Another valued tool is guardrails—building structures in our lives that prevent going too far in either direction. Tools also include finding comfort in the discomfort of paradoxes, and building habits that allow for learning and dynamic responses. These tools can enable two patterns of both/and thinking.

The first pattern is a win/win solution. We call such creative integration a mule—the hybrid that is stronger than a horse and smarter than a donkey. Einstein’s theory of relativity is a classic mule. Jeremy Hockenstein is a social entrepreneur who built his organization Digital Divide Data to bring together the desire to do good while doing well, a social mission with a financial bottom line.

When people think of both/and, they’re typically looking for ideal win/wins. Consider tensions between work and life, self and others. We might open a daycare so that our work includes caring for our own children; or we charter a fishing boat so that our life passion becomes our work. Sometimes mules can be found, but not often.

More regularly, we navigate paradoxes by being consistently inconsistent—tightrope walking. Tightrope walkers focus on a point far in the distance, then start moving forward, making microshifts between left and right. They never achieve a static balance but are constantly balancing. To avoid falling, they can’t veer too far to either side. Navigating work/life tensions involves constant shifting. We shift time and attention—some nights we stay late at the office, while other nights we make it home for dinner. If we move too far to overemphasize work, we might burn out. If we overemphasize life, we might lose our job. Alternatively, the product design teams that I studied which navigated between demands for the present and for the future did so by making ongoing decisions about how to allocate resources, structure teams, and others.

5. Navigating paradox is paradoxical.

You might ask, “Isn’t the choice between either/or and both/and an either/or itself?” Well, yes. Navigating paradox is paradoxical. The tools for embracing paradox and applying both/and thinking are themselves contradictory and interdependent.

“We need to change our mindsets to embrace both/and thinking and shift emotions to find comfort with the discomfort of paradoxes.”

For example, either/or can be a means to both/and. Either/or involves making clear decisions. In the pattern of tightrope walking, we are making clear decisions, but these microdecisions are in service of embracing competing demands over time. We want to embrace both self and other, give and take, work and life, so we adopt patterns of decisions that sometimes focus on one and at other times shift to the other. Once in a while, we find a creative integration in this process—the moment where work and life, self and other come together—a mule on the tightrope. For example, one of our colleagues learned to use travel as a chance for integration. She could sometimes bring her family with her when going on business trips. Her family could learn more about her job while also spending time together enjoying a new city.

Similarly, the tools for navigating paradoxes are paradoxical. We need tools that can be adopted individually. We need to change our mindsets to embrace both/and thinking and shift emotions to find comfort with the discomfort of paradoxes. Head and hearts, cognition and emotions, rationality and intuition—they sometimes pull us in opposite directions, but can also reinforce one another. We also need clear static boundaries, such as guardrails, to scaffold decisions. We also need to experiment and make changes over time. Stability and change, boundaries and dynamism, structure and experimentation. These tools are oppositional. Yet stable boundaries can unleash creative experimentation, while change can lead to new and clearer boundaries.

Navigating paradoxes is not for the faint of heart. We all face growing challenges individually and collectively. Embracing paradox and adopting both/and thinking have become critical tools for personal well-being and global sustainability.

To listen to the audio version read by authors Wendy Smith and Marianne Lewis, download the Next Big Idea App today: