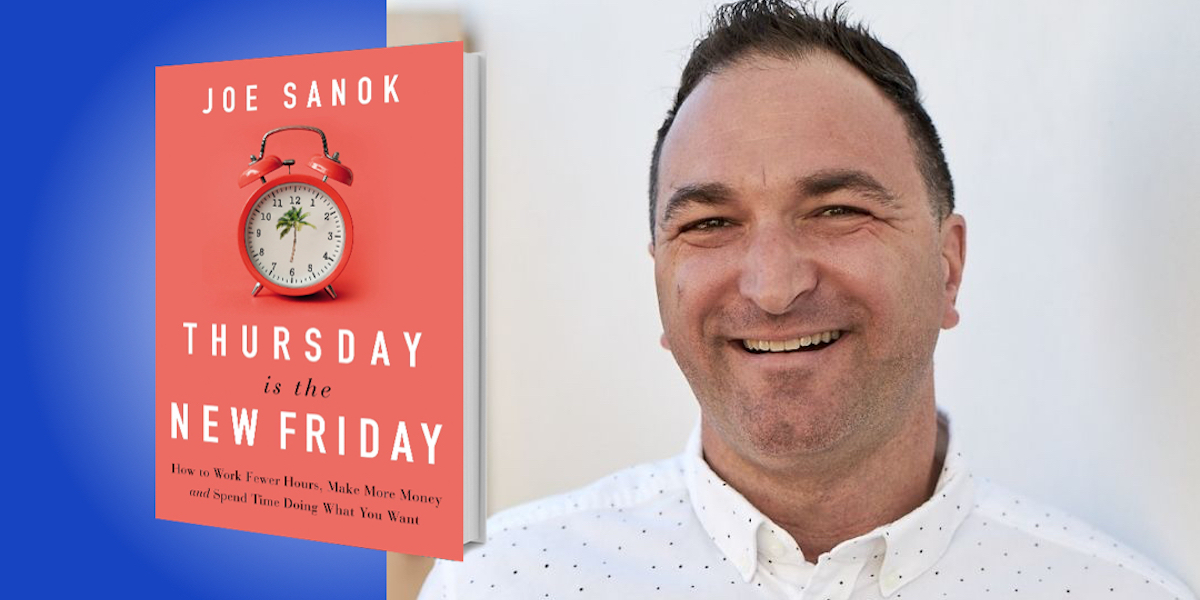

Joe Sanok is a keynote and TEDx speaker, business consultant, and podcaster. He writes for the PsychCentral website, and his writing has been featured in the Huffington Post, Forbes, GOOD Magazine, Reader’s Digest, and Yahoo! News. He is the author of five books.

Below, Joe shares 5 key insights from his new book, Thursday Is the New Friday: How to Work Fewer Hours, Make More Money, and Spend Time Doing What You Want. Listen to the audio version—read by Joe himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Time is an invention.

The ancient Babylonians created the seven-day week based on seven major celestial figures: the Sun, the Moon, Earth, Mercury, Venus, Mars, and Jupiter. The Romans, meanwhile, had a 10-day week, and the Egyptians had an eight-day week. So while a day and a year mark real events in the solar system, the week is a completely arbitrary human invention.

The length of the workweek has varied, too. In the 1800s and early 1900s, the average person worked 10 to 14 hours a day, six to seven days a week. It wasn’t until 1926 that the 40-hour workweek became an American standard.

At a certain point, it started becoming acceptable for Friday to be a less productive day in the office. People would leave early, or we would have birthday parties or baby showers, or we might do a team-building activity. I often say that for a long time, Friday has been cheating on the workweek with the weekends.

So why not just call it what it is? Why not make Friday part of the weekend, and have a very productive four-day workweek? It’s up to us to make this work by learning how to be more productive Monday through Thursday, and to really slow down Friday through Sunday.

“In the 1800s and early 1900s, the average person worked 10 to 14 hours a day, six to seven days a week.”

2. Know your internal inclinations.

Top performers do three things well. And if they don’t do them naturally, they figure out where they need to grow. These three things are:

- Curiosity: While this trait comes naturally to children, business leaders need to cultivate it. When things don’t go their way, they need to train themselves to ask questions, dig into the data, and experiment with a new approach.

- An outsider perspective: Studies have shown that outsiders have unusual influence on groups and can prod insiders to be more creative. Leaders need to practice bringing this perspective to their teams.

- The ability to move fast: While accuracy is valuable, top performers show a bias toward speed, knowing that perfection is the enemy of progress. Getting a minimum viable product to market is almost always preferable to endless tinkering.

Ask yourself which of these tendencies come naturally to you, and which you need to work on.

3. Slow down to speed up.

We’re not our best and most innovative when we’re stressed. When I was starting a trek through the Chetwan National Park in Nepal, my guide said, “If we get chased by a wild rhinoceros, climb a tree.” And yet, an hour later when a rhino I was photographing decided to charge me, I took off running. In high school I had been a sprinter, and I just ran for my life, pushing the jungle out of the way and running as fast as I could. Luckily, I survived. But when I walked back, I found my guide up in a tree yelling down at me, “Why didn’t you climb a tree?”

Why didn’t I climb a tree? Because running was what was familiar to me, and when stressed out, I reverted to the familiar.

“When we rest our brains, our best work comes out.”

I host an annual week-long event called Slow Down School for entrepreneurs on the beaches of Northern Michigan. For the first few days, we just slow down. We go hiking. I bring in massage therapists and yoga teachers. And we genuinely let our brains rest, with the idea that when we rest our brains, our best work comes out. Then, during the latter part of the week, the participants do creative sprints related to their work projects. One participant had been struggling for months with outlining a book he wanted to write. After those first few days of slowing down, when it came time to work, he outlined his first nine chapters in a single 20-minute sprint. It just flowed. Amazingly, slowing down actually helps us speed up.

4. Know your sprint type.

Sprinting isn’t a new idea. Maybe you’ve already tried sprinting or batching in your own work, with mixed results. We’re learning now, however, that different people have different styles of sprinting that work best for them.

A time block sprinter will set aside a minimum of one hour and a maximum of four hours at a time to work on one specific task, usually broken up into 20-minute increments. This person tends to stay highly focused during this time and take minor breaks.

A task switch sprinter, on the other hand, does better by intentionally switching tasks every 20 minutes or so. They set a timer and determine each sprint’s purpose. For example, they may work on copy for a blog post for 20 minutes, then do a call with a client lead. Next they’ll check email, maybe walk outside during another call, and then maybe approve a project’s final stage.

The other factor to consider is when you sprint best. Automated sprinters set a regular (usually weekly) sprint time. For example, I did all of my writing for this book on Thursdays, saving other days for my consulting, podcasting, and other projects. Intensive sprinters, on the other hand, schedule periodic, multi-day retreats to get their sprints done. A friend of mine does this by renting an Airbnb that’s walking distance from a vegan restaurant and has a nice backyard, and he’s super productive.

“Different people have different styles of sprinting that work best for them.”

So to get more done, figure out what sprint type is best for you.

5. Start your “Thursday Is the New Friday” experiment.

So how do you actually start a movement toward a four-day workweek? The best way is by experimenting. Get together with the people you work with, and propose a four-day workweek experiment for a certain period of time. I would suggest a minimum of two months. Also decide how you will measure success: Will it be based on monetization? Will it be based on customer acquisition? What is it going to be based on that is meaningful to your company?

Next, agree on some rules that will help your team fully slow down over your three-day weekend. For example, no checking email on the weekend. No returning work texts until Monday morning. And decide what you will do on the weekends as well—“I’m going to shop for groceries for my family,” for example, or “I’m going to get all the laundry done.” What things will you do to optimize your brain over the weekend, so that you can come to work on Monday morning and work as hard as you can for those four days?

During your experiment, look at your weekly metrics and measurements, and report them to the team. If productivity is dropping, see if you can make some corrections to your team’s workflow. While the four-day workweek won’t be a good fit for every team, experiments around the U.S. and abroad have shown that it leads many workers to be happier and more productive.

To listen to the audio version read by Joe Sanok, download the Next Big Idea App today: