Clive Lewis is a business psychologist specializing in individual, team, and organizational behavior. He has worked with executive teams and governments for over 20 years, mediating and facilitating hundreds of one-on-one and team discussions for thousands of people.

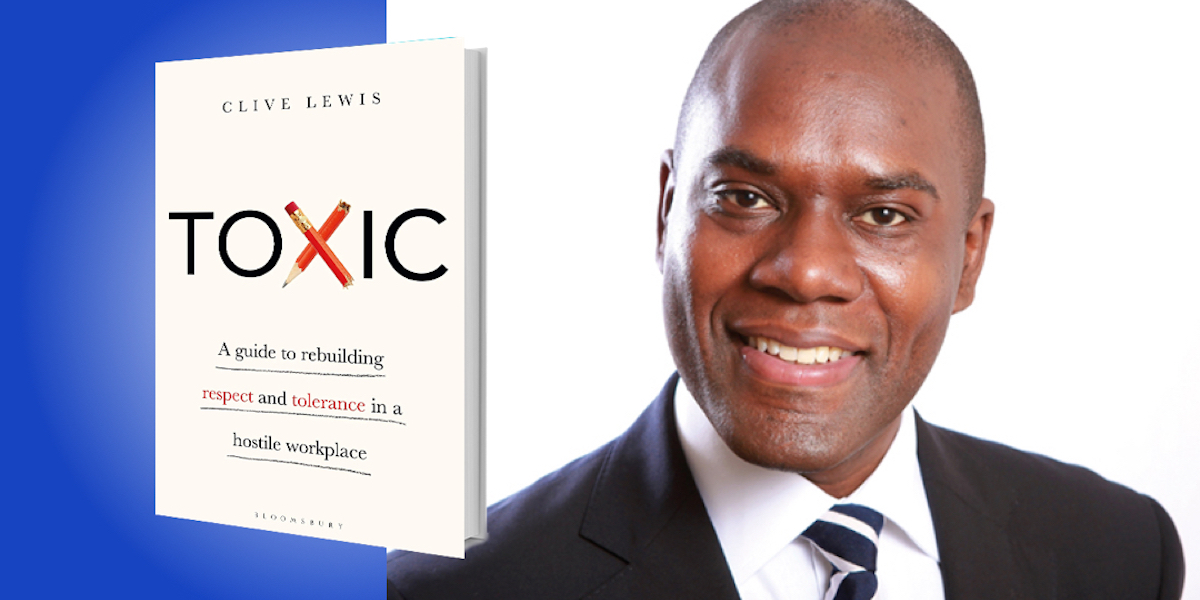

Below, Clive shares 5 key insights from his new book, Toxic: A Guide to Rebuilding Respect and Tolerance in a Hostile Workplace (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Clive himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The Toxic Triad.

There are usually three strands that are consistent and interconnected when significant difficulties surface in the workplace: organization systems, line management capability, and attitude of the employee. These all contribute toward a toxic environment.

A toxic organization exhibits low levels of trust, has misaligned organization systems, and incapable line managers who work hard to preserve their status at all costs. Employees are unwilling or fearful to take responsibility for their actions. A toxic organization is likely to have slow, painful, bureaucratic and non-inclusive decision-making. It likely fails to make adequate resources available to carry out job roles, as opposed to a non-toxic organization having fully aligned systems and structures with a clear purpose.

A toxic line manager lacks the competence required to fulfill their role. Their ethical deficit is characterized by a pattern of behavior that includes a demonstrable lack of regard and compassion for the well-being of team members. This might look like someone who is unable or unwilling to conduct routine one-on-one conversations, or is focused on micromanagement, versus someone who demonstrates confident vulnerability, or perhaps is exceptionally knowledgeable about their functional area of expertise.

A toxic employee is prone to seek opportunities to sow discord and division. They can be characteristically uncivil and are far more likely to seek retribution than offer forgiveness. Their delivery of results can be questionable. They can also endeavor to keep furtive actions against colleagues away from attention, and they might have a series of dysfunctional relationships.

“When a tackler senses danger and deals with it, the dodger will avoid it and hope that it goes away or is dealt with by someone else.”

2. Demonstrate civility and respect.

There is a golden rule, which is “Do to others as you would have them do to you.” Rather than focus on negative behaviors to avoid in the workplace, organizations would do well to emphasize positive behaviors to adopt.

To enhance civility and respect in the workplace, it helps to embrace a few simple ideas. For instance, say “please” and “thank you.” Recognize the work of others, rather than suggesting it is your own. Listen to colleagues, making sure everyone feels like part of the team. Speak respectfully to others, giving them a smile or being attentive in meetings rather than catching up on emails and texts. Choose face-to-face communication over electronic messaging. Be punctual. Hold the door open for someone, or ask colleagues if they would like a coffee or water as you go to get one for yourself. Research indicates that these gestures—referred to as “thin slices”—contribute a great deal towards making workplaces less toxic and far more civil.

3. Are you a tackler or a dodger?

There is a spectrum when it comes to having difficult conversations, with dodgers on one end—that’s people who procrastinate dealing with issues—and tacklers on the other end, who tackle situations head on and very quickly. Many of us fall somewhere in between.

Recognizing the need to have a difficult conversation about a behavior in the workplace will depend largely on how you came across the problem. As has been well documented in the press and elsewhere, toxic behavior happens at all levels. Witnessing behavior you find questionable can bring about deep conflict, as you may not be quite sure how to approach the issue, or whether you should report it at all. A good rule of thumb is to ask yourself how you would feel if you were the victim in the case. How would it make you feel to be on the receiving end of that behavior?

When a tackler senses danger and deals with it, the dodger will avoid it and hope that it goes away or is dealt with by someone else. This might work one time out of four or five, but it only takes one person in the affected chain—which grows larger with every ignored opportunity to deal with it—to realize that someone, including you, had the opportunity to stop it and didn’t. So your respite is only short-lived, and the end result is usually far worse. Spending your days trying to avoid certain people and hoping you don’t get found out is not a fun way of living your life.

“Many managers can be stuck fighting the small fires, and have lost the ability to collect and analyze data that would shed light on the larger problem.”

In terms of the actual conversation, there are some practical guidelines: Hold the meeting in private, maintain eye-contact, avoid accusations, and stick to the facts. Don’t accuse or create motives where none were present.

Another category is the “reckless tackler.” The reckless tackler is someone who recognizes that a conversation needs to be held and jumps in with both feet—often leaving a trail of carnage in their wake, as they haven’t thought through the right way to prepare, perhaps by gathering evidence and facts to call on throughout the conversation.

4. Organization diagnosis.

It isn’t straightforward to answer why organizations become toxic, or what the impact might be, or indeed the prescription that is required for recovery. Human behavior can be convoluted and incredibly complicated. It requires an understanding of human social behavior and in many cases, abnormal human social behavior. It also requires an understanding of psychology, sociology, neurobiology, sensory cues, hormones, early experiences, and so on.

One of the founders of behaviorism, John Watson, suggested that behavior is completely malleable, and that it can be shaped into anything in the right environment. I’m sure there are many Chief Executives and Chief Human Resource Officers that wish it were that simple. In a normal workplace, you are likely to witness a range of behaviors including cooperation, competition, aggression, violence, empathy, sympathy, schadenfreude, spite, forgiveness, reconciliation, revenge, and reciprocity. These can all be experienced within a week at a large business employing thousands of people.

Some of the steps an organization can take to look at this area of organization diagnosis includes data collection, data interpretation, a preliminary diagnosis, and then testing to see whether potential solutions will work. Many managers can be stuck fighting the small fires, and have lost the ability to collect and analyze data that would shed light on the larger problem.

“The longer conflict rumbles on, the more difficult it can be to break deadlock.”

There are plenty of ways that data can be collected and analyzed to benefit an organization. For example, exit interviews can show termination and retention trends. And how many grievances lead to where the conflict lives? An opportunity exists to analyze data over a period of time. The data will suggest where the problems are, and should be analyzed prior to the issues being presented at board level.

Bringing organization diagnosis back into the spotlight holds many benefits for everyone. Introducing a scientific process for diagnosing problems will give a more accurate and customized report of the symptoms, and reveal where attention is needed. The more accurate the diagnosis, the smoother the recovery.

5. Reap the positive results of mediation.

There are a number of tools that can help resolve conflict situations. Since becoming an accredited mediator nearly 20 years ago, I’ve been astonished by the transformational impact mediation can have. My own case load has led to savings of over ten thousand days of management time, hundreds of people choosing to come out of grievance or rights-based processes, and numerous people returning to work after long periods of sickness and absence. I have also seen results at a strategic level, which have involved passenger planes being able to continue flying, pharmaceutical drugs remaining on the market, and retail stores staying open.

Mediation is a process used for resolving disputes in which a third person helps the parties negotiate a settlement. It can be unbelievably liberating to resolve issues that arise from toxic relationships. If your organization is not yet using mediation to help solve disputes, you are well behind the curve. It only takes place over one day, and is essentially a facilitated, future-focused conversation.

Unfortunately, the longer conflict rumbles on, the more difficult it can be to break deadlock. If you imagine two people standing and facing each other, when a dispute occurs, the two people turn their backs. Over time, with their backs still turned, they move further and further apart. The longer they refuse to speak to each other, the further apart they drift.

When a mediator is commissioned, she or he will reach out and attempt to draw the parties toward each other, with their backs still facing each other. Eventually the mediator builds enough trust to prompt them to turn and face each other to allow conversation and dialogue to begin.

To listen to the audio version read by Clive Lewis, download the Next Big Idea App today: