Suleika Jaouad is an author, journalist, and activist. She won an Emmy award for her New York Times column, Life Interrupted, which she wrote during her four years fighting cancer. She survived the illness, but the story doesn’t end there.

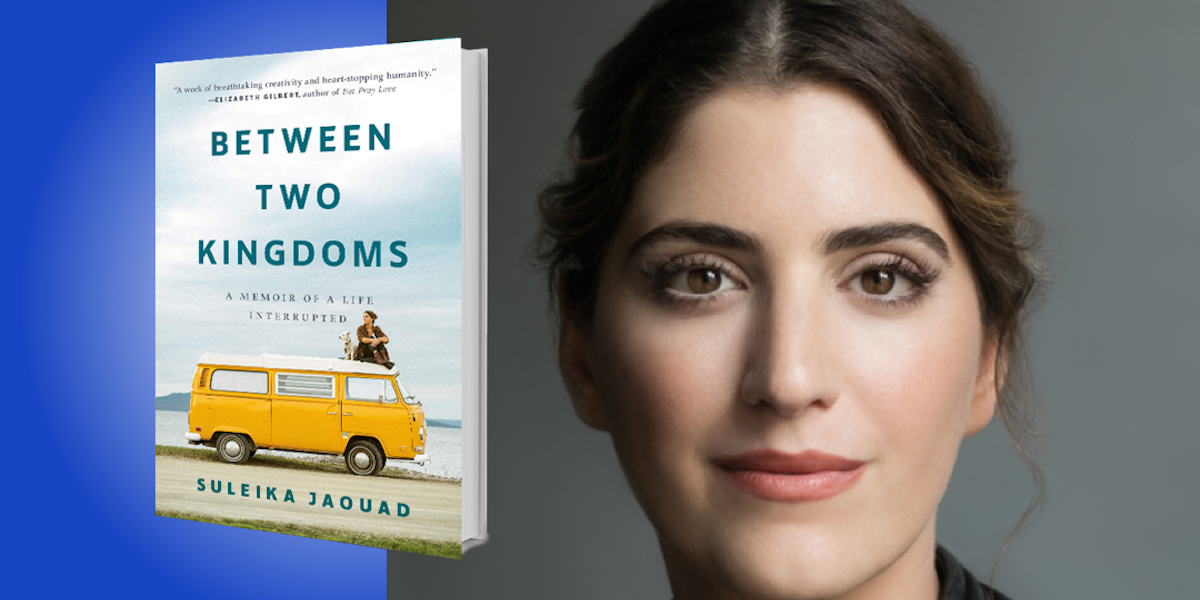

Below, Suleika shares 5 key insights from her new book, Between Two Kingdoms: A Memoir of a Life Interrupted (available now from Amazon). Download the Next Big Idea App to listen to the audio version—read by Suleika herself—and enjoy Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Moving on is a myth.

I was diagnosed with leukemia when I was 22. When I finally emerged from nearly four years of treatment, I learned the brutal lesson that surviving is not the same thing as living. It should have been a celebratory milestone, but in truth, I had never felt more lost. I was lost in a liminal space, where the survival skills I’d honed in the context of illness were no longer useful.

The outside world felt overwhelming and frightening, and I was struggling to find my place among the living. I wasn’t well enough to work a traditional job, seeing as I needed to take a break in the middle of the day for a four-hour nap. As much as I wanted to, I couldn’t live like a normal 27-year-old. I couldn’t go out dancing with friends, and if I did, I paid for it dearly with three days in bed. I was still wrestling with the wreckage, with the physical and psychological toll of illness, and with the grief of losing so much. Through my own experience, and those of dozens of others I’ve interviewed who are navigating the aftermath of a major loss or trauma, I’ve learned that moving on is a myth. It’s the delusion that you can build a barricade between yourself and your past, that you can bury your sorrows and that you’re among the lucky few who get to skip over the hard work of grieving and healing and rebuilding. Instead, I’ve come to understand that while you can’t move on, you can find a way to move forward with it.

2. Healing is a creative act.

When our lives are dramatically disrupted by illness or a global pandemic or some other sorrow, it’s important that we create new habits, goals, routines, and rituals. Trying to apply old ones in such circumstances is a recipe for frustration. We have to reassess our days and what they can contain. We have all kinds of ceremonies and rites of passage that help us honor different phases of life and move from one to the next: birthdays, bar mitzvahs, weddings, baby showers, funerals. These are all ritual experiences that help us bridge the distance between “no longer” and “not yet”—but re-entry after a traumatic experience has no such clear ceremony.

“If you are depressed, you are living in the past. If you are anxious, you are living in the future. If you are at peace, you are living in the present.”

In the aftermath of my illness, I had to invent my own healing ritual. Searching for a path forward, I embarked on a 15,000-mile, solo van trip around the United States. I traveled across 33 states and visited 22 strangers, all of whom had written to me, while I was sick, in response to my New York Times column, Life Interrupted. I visited a school teacher in California grieving the death of her son. I visited a man on death row in Texas. I visited a teenager in Florida who was also recovering from cancer. These encounters taught me the importance of community, but more than anything, they taught me that you can’t go back to how things were. Recovery is not about salvaging the old, though the word may suggest otherwise. It requires imagination to uncover the new, to discover who you are now. Healing is a creative act.

3. Whenever we travel, we actually take three trips.

When I was on that road trip, while recovering from cancer, I met all kinds of unexpected characters. One was a sculptor and psychotherapist named Rich, in Northern California. He gave me some advice that stayed with me long after our visit. He explained that when we travel, we actually take three trips. There’s the first trip of preparation and anticipation, packing and daydreaming. There’s the trip you’re actually on, and then there’s the trip you remember. The key is to keep all three as separate as possible, to be present wherever you are right now. Especially in this last year, when we’ve been mired in so much uncertainty, it’s easy for our thoughts to time-travel back to what things were like before, or to anxiously obsess about what might happen in the future.

To learn to swim in that ocean of not knowing, to learn to stay anchored in the present—this is our constant work. I’m reminded of the words of ancient philosopher Lao Tzu, who said, “If you are depressed, you are living in the past. If you are anxious, you are living in the future. If you are at peace, you are living in the present.”

“Healing is figuring out how to co-exist with pain, without either pretending it isn’t there or allowing it to hijack our days.”

4. Feel the pain.

We do all kinds of things to avoid experiencing pain. We dodge, numb, armor ourselves against it, but those tactics don’t rid us of pain—they merely delay it. I used to think healing meant purging the body and the heart of everything that hurts, but I’ve realized that’s not exactly how it works. Healing, instead, is figuring out how to co-exist with pain, without either pretending it isn’t there or allowing it to hijack our days. It’s learning to embrace ghosts, to carry what lingers, to live within an armored heart. The many losses I endured during illness comprises the loss of life as I knew it, my identity, friends and fellow cancer comrades, and the loss of a romantic relationship. All of that left me guarded and spent.

When the grief within is raw, it’s hard to open up to the possibility of a new life, new love, because it requires us to open ourselves to the possibility of new loss. Living with that openness means feeling pain, but the alternative is feeling nothing at all. And the truth is you can’t protect yourself from loss, be it a breakup, a betrayal, or something as big and blinding as death. Trying to evade heartbreak is how we miss out on our people, our purpose—and I can’t think of a better response to life’s hardships than love.

5. Our health isn’t binary.

Susan Sontag describes illness as a metaphor for how we all have dual citizenship in the kingdom of the sick and the kingdom of the well. I’ve come to understand that our health is not binary; rather, the border between the two realms is porous. For instance, I’ve been cancer-free for six years now, but I still have a compromised immune system and struggle daily with fatigue. I still feel hypervigilant and worried that my cancer might come back. I still grieve every day for my fellow cancer patients who didn’t make it. And during the pandemic, I’ve been wearing face masks and carrying around several bottles of hand sanitizer at all times.

The truth is we are not well or unwell, not whole or broken. We all exist somewhere in the messy middle, now more than ever. The pandemic has left no one unscathed. Whether you’ve had COVID and you’re suffering from the lingering long-term side effects, whether you’ve lost a loved one, or whether you’re reeling from months of disruption and isolation, embracing the in-between is the key to making that wilderness a home.

To listen to the audio version read by Suleika Jaouad, and browse through hundreds of other Book Bites from leading writers and thinkers, download the Next Big Idea App today: