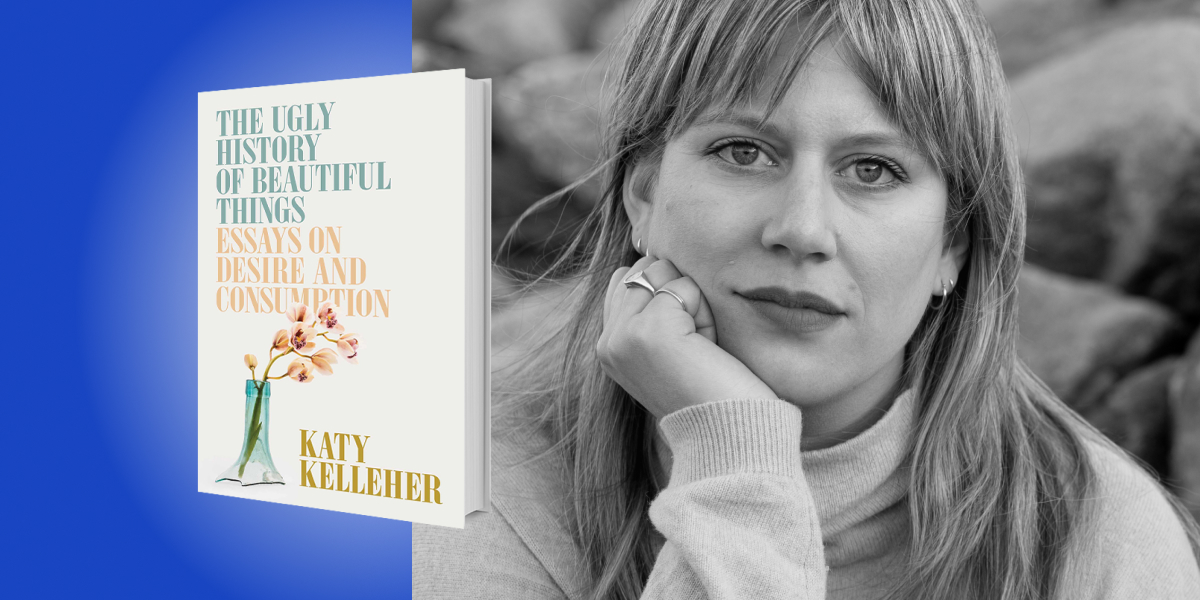

Katy Kelleher is an art, design, nature and science freelance writer whose work has been in the New York Times, The Guardian, American Scholar, and Town & Country. She is a frequent contributor to The Paris Review and spent several years writing a popular column on color called Hue’s Hue.

Below, Katy shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Essays on Desire and Consumption. Listen to the audio version—read by Katy herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Beauty is transient, life-affirming, and sacred.

There have been times throughout my life when living felt too difficult to continue. Once, as a teenager, I attempted suicide with a bottle of prescription pills because I couldn’t imagine a life without pain. I hadn’t come to accept that suffering was inevitable, but so was love, lightness, and joy.

It took years, and many hundreds of hours of therapy, to see that my life was as unremarkable as my pain. It also took years to understand that there was a reason to keep getting up and leaving my bed. That reason was looking for moments of beauty. I went through each day waiting to see something worthwhile: a glimpse of the indigo Catskills over the Hudson or a flash of butterfly wings. Or perhaps a piece of artwork, so finely made and ancient, that it made me stop and stare, marveling that human hands did this, that human genius that could produce such lasting artifacts. Now in my mid-thirties, I feel as though I finally understand what can replace God for us lapsed Catholics: we can love beauty, and that is enough.

2. Like religion and faith, beauty is cultural and malleable.

Desire can be changed and shifted. Appreciation can be learned, sharpened, and widened. Have you ever seen a diamond? It’s a stone. Obviously, a clear one that is very popular in jewelry, but it’s also a chemical marvel, one of the strongest materials on earth thanks to its tetrahedral structure. As light passes through these hunks of pure carbon, it gets bent and scattered, resulting in that famous, coveted sparkle. Sometimes, diamond dealers call this “fire” but just as often, you’ll hear it referred to as “dispersion.”

“The idea is that diamonds are useless, yet worth quite a lot, while water is necessary, yet worth next to nothing.”

This quality, attractive though it is, isn’t why diamonds are worth so much money. Both beauty and strength are part of the equation, but there are so many other factors in play, the most important of which is perceived value. Economist Adam Smith wrote of the “diamond-water paradox.” To paraphrase, the idea is that diamonds are useless, yet worth quite a lot, while water is necessary, yet worth next to nothing.

There is beauty in a diamond, but there is also beauty in ice; rigid and cold, reflecting winter’s light and turning blue in the dusk. There’s also beauty to be found in lesser-valued stones, quartz, turquoise, topaz, or malachite.

Stones have a beauty that we can’t deny, but we don’t have to follow predetermined lines of desire or consumption. We are capable of appreciating and wanting beauty that exists outside our immediate cultural sphere. Once upon a time, women didn’t wear diamond rings, they wanted color—rubies, emeralds, and turquoise. The impulse wasn’t to buy a stone that would last forever, but one that would signal their commitment and showcase their good taste. While beauty is a part of fashion, fashion also shapes beauty. No trend lasts forever.

3. Both desire and beauty are intensified by the shadow of death.

Take perfume: most people have opinions and preferences about smell that seem, to them, to be inherent, or at least, logical, and perhaps even influenced by evolution. Some of them may be, but perfume is an art form that can upend what we know about desire and repulsion. For a long time, we assumed that it was in our nature to dislike certain scents, like that of rotting corpses or human feces. Disgust serves an evolutionary purpose, right? Well, it’s much more complicated than that.

“Perfume is an art form that can upend what we know about desire and repulsion.”

Jasmine, one of the most prized scents in perfumery, contains a compound that can also be found in decomposing bodies and toilets. It’s part of the bouquet, part of the aroma of jasmine, yet when we smell a jasmine-heavy perfume, we often think of it as “sexy,” “erotic,” “warm,” or even “clean.” Our brain registers the familiar foul smell but it also registers the rest of the scent: the prettiness and the sweetness. One of my favorite perfumes is called Jasmine and Cigarettes (Jasmin et Cigarette in French). For some reviewers, this perfume is unbearable, supposedly smelling like ashtrays and bar bathrooms, but for me, it smells intoxicating.

It’s not just jasmine or tobacco that can elicit these polarizing responses; musks are also strangely compelling. Traditionally made from the anal glands of animals, we now wear synthetic versions of musk almost every day. Studies have shown that the average consumer reads white musk as “clean” or even “soapy.” It’s amazing how much and how little our noses know, but that’s part of beauty. It’s complicated and strange and so often more than the sum of its parts.

4. Beauty is damaging and dangerous.

Throughout history, our lust for beautiful objects has caused incredible damage. For example, mining scars and pits at the surface of the earth, silk-worm farming that involves boiling millions of creatures alive, or creating lab-grown gemstones that take a good deal of fossil fuel energy. Our appetite for fast fashion and the global demand for cheap clothing has caused many Americans to turn a blind eye to the slavery and abuse that happens abroad.

“You can find examples of people dying for beauty in every corner of the globe and in every chapter of history.”

Human rights violations happen closer to home too. For example, engineered stone countertops are becoming more popular, yet in the making of these slabs, workers choke from silica dust. Their lungs get scarred by the white powder and they can die untimely deaths. You can find examples of people dying for beauty in every corner of the globe and in every chapter of history: some of them choose this fate, while others are forced into it.

5. Beauty doesn’t need to be so hard-won or fraught.

You don’t have to be plagued with guilt. The world doesn’t have to work this way—those of us who love beauty have options. You don’t have to deny what you find beautiful or retrain yourself to find different things beautiful. This of course can happen and can be a really wonderful thing to do. It’s always great to expand our possibilities of pleasure!

Beauty doesn’t need to be accumulated or owned. If you view beauty as an action, a moment, a thing that happens between a person and an object, then you can also view beauty as an event worth seeking out. You can recreate it and because of that, ownership becomes a lot less important.

People visit museums, cemeteries, gardens, and parks for many different reasons; beauty is just one of them. It’s worth remembering that we’re incredibly lucky to have access to public spaces, where beauty exists. That is no accident either, as these are some of America’s best public projects, designed to raise the quality of life for all people. It’s worth remembering that our civic duty to one another isn’t all drudgery and sacrifice. Sometimes, it’s about sharing beauty and experiencing it together.

To listen to the audio version read by author Katy Kelleher, download the Next Big Idea App today: