Kyo Maclear is an essayist, editor, author, and children’s book author. She teaches creative writing with The Humber School for Writers and the University of Guelph Creative Writing MFA. She received a Ph.D. from York University in the environmental humanities. Her short fiction, essays, and art criticism have been published in Orion Magazine, Asia Art Pacific, LitHub, Brick, The Millions, The Guardian, Shambhala Sun, and The Globe and Mail (Toronto), among other publications.

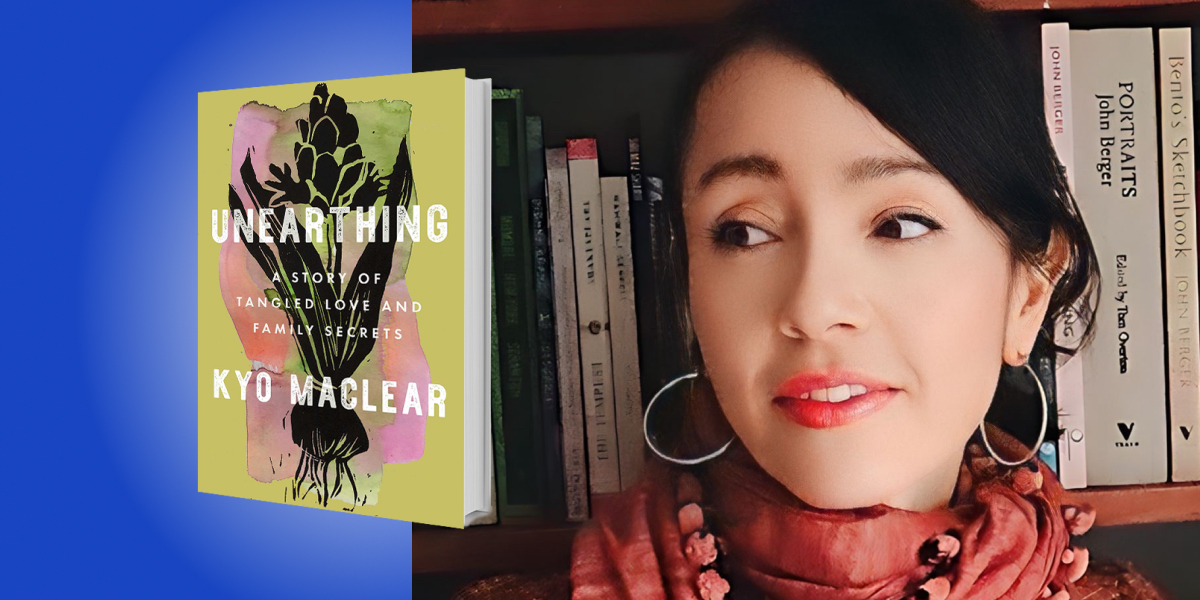

Below, Kyo shares 5 key insights from her new book, Unearthing: A Story of Tangled Love and Family Secrets. Listen to the audio version—read by Kyo herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Our common stories connect us.

In 2019, I took a DNA test and discovered that my father, who had died just three months earlier, wasn’t biologically related to me—and so began a journey to uncover what happened. As exceptional as the experience seemed, I knew I was far from alone. Forty million people have participated in recreational DNA testing over the past decade. There has been an explosion of DNA surprises as a result—one of the most common surprises being the discovery of misattributed parentage.

In other words: Family secrets, even life-shifting ones, are very common.

Realizing that our stories are not rare, that they often belong to an entire social and cultural environment, can be freeing. I was raised in a family that said, “We don’t talk about private things.” As an only child, I was taught to be aggressively self-reliant and to see sharing as weak and even shameful. It took me a long time to realize that shame is propagated through enclosure rather than disclosure. Shame multiplies when we close windows and stop ourselves from expressing connection, vulnerability, or need—when we create social taboos around sharing the hard but common stuff.

All to say: I believe in sharing the common. I believe in reading as a Commons.

2. It’s okay to have an identity crisis!

In 2019, as I crawled out of a story I had known into a new, unfamiliar one, everything seemed wobbly and uncertain. “Identity crisis” is the term often used for such moments of flux and change but the truth is identity is never static. If we’re lucky, growth will pull at the contours of the self and we will continue to go through life having encounters that expand and even dissolve us.

“Reading can invite us to move beyond our narrow identity borders.”

In other words: the quake and tilt are okay. Of course, that doesn’t mean flux is easy. In the period when my biological father was still a mystery, I definitely felt unsettled but I also felt, in a small but significant way, that I belonged to the entire world. When I stopped thinking of the experience in terms of a “crisis” that needed to be resolved, something in me softened. I remembered a sense of suppleness, a feeling that my coastlines were pliant and I could be, and include, many things—even five late-arriving siblings!

The good news is that reading can invite us to move beyond our narrow identity borders, to bump into others we might rarely meet in the normal run of things—other people and our other selves—to catch the sound of this other breathing.

3. Every story has an understory.

Every story had an understory and sometimes a hidden, teeming world of substories. There may be underseen players who are overshadowed by the big actors.

In my own case, I grew up with a white reporter father who had Big Protagonist energy. While my father zoomed around the world on his news missions, impossibly active, my mother and her Asian friends (many of whom were married to white reporters) were relegated to supporting roles.

Well, it turns out my mother had her own Big Story.

Turning my attention to the understory of my family was a reminder that our versions of reality are always partial; dominant stories are often driven and overturned by underestimated actors. I’ve come to accept and even love the idea that we “see” only a tiny fraction of what’s actually going on around us.

4. Life is about welcoming the stranger.

When I was little, I was fascinated by a book called The Moomins and the Great Flood by Tove Jansson. It was the tale of a terrible disaster but it was also a story about the formation of an extended family where misfits and orphans were welcomed into the fold. Survival for the Moomins meant pitching a large tent and practicing care beyond the Moomin family sphere. I think about this book a lot, about what it means to pitch a large tent and to proceed with the idea that there are infinite forms of family making.

“I sometimes imagine everyone is a cousin or sister who has arrived in my inbox.”

Every day I receive a notification about new DNA matches. Usually, they are second, third, and fifth cousins. I no longer check them. For all I know, I have a new sibling. As a thought experiment, I sometimes imagine everyone is a cousin or sister who has arrived in my inbox. (Try doing this in an overcrowded and tense waiting room.) I think of this as a secular version of Judaism’s “welcome of the stranger.” I try to invite that spreading, inclusive sense of belonging. That open door that says permeability is our strength.

5. Ancestry is also what you carry forwards.

My parents were very caring but they were also catastrophists who made me believe the next tide would surely wash us all away. My father was a child of the Blitz who went on to become a war reporter, so you could say large-scale emergencies were his métier. My mother lived through the firebombing of Tokyo. They both knew explicit danger so their ambient sense of worry and their doomier sense of preparedness made a degree of sense. I grew up in London and Toronto, however, so it was a little unusual to walk around waiting to be carried away to sea. In other words, their blueprint wasn’t a bad one for wartime survival but felt anomalous in relative peacetimes.

As a parent, I have had to constantly check my (innate? inherited?) catastrophic tendencies. I’m grateful for all my parents gave me. How they equipped me. But I also know I don’t want to pass a lot of that down the line.

Ask yourself: How can you unspool your histories and long lines of lineage into the future in a friendlier way? What do we inherit? And what do we reproduce?

To listen to the audio version read by author Kyo Maclear, download the Next Big Idea App today: