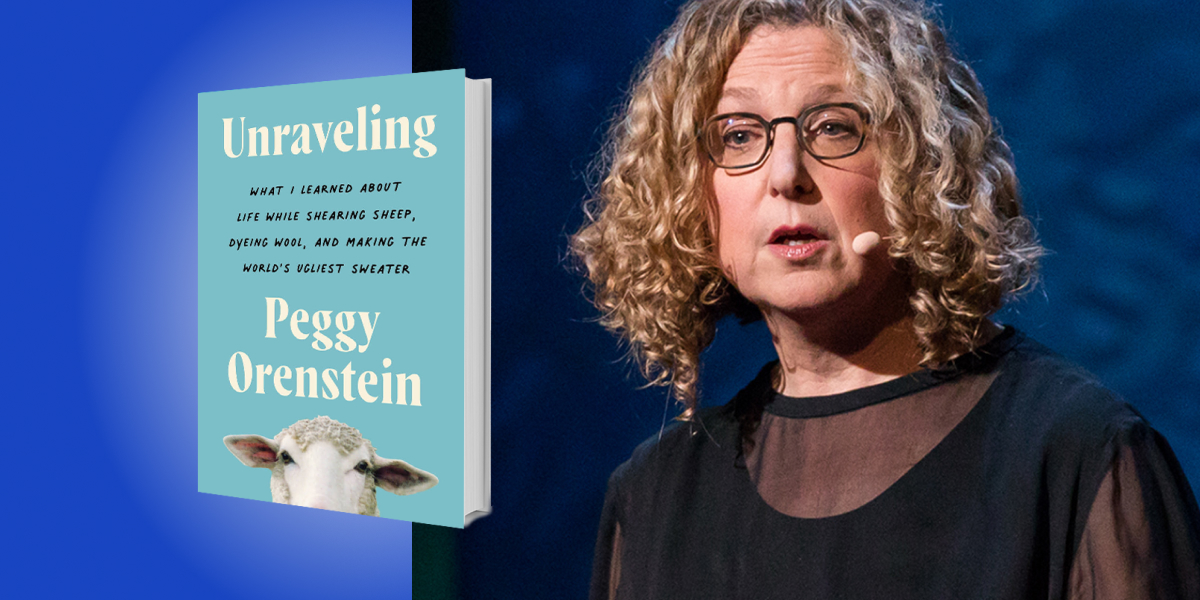

Peggy Orenstein is a New York Times bestselling author of Cinderella Ate My Daughter, Waiting for Daisy, Flux, and Schoolgirls. A contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine, she has been published in USA Today, Parenting, Salon, the New Yorker, and other publications, and has contributed commentary to NPR’s All Things Considered.

Below, Peggy shares 5 key insights from her new book, Unraveling: What I Learned About Life While Shearing Sheep, Dyeing Wool, and Making the World’s Ugliest Sweater. Listen to the audio version—read by Peggy herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Start thinking about your clothing the way you think about your food.

Breaking down a garment to its basic “from scratch” components, learning to shear sheep and process fleece, or spin and dye yarn makes you start asking, “Why don’t we think about our clothes the way we think about our food?” In terms of ethics and sustainability, the impact on the planet or on the people who make our clothing isn’t always something we think about before buying clothes. In our lifetimes alone, there has been a decline in the quality of natural fabrics. Synthetics are now in 70 percent of the clothing we wear. Nylon, polyester, viscose, rayon, Dacron, acetate, Lycra spandex—are all just fancy words for petroleum-derived plastics.

In the past, new clothing lines came out a few times a year; you got your school clothes, and your summer clothes and you were done. Those synthetics along with draconian labor practices have made room for fast fashion outlets like H&M and Zara, which produce hundreds of styles a week. More recently, ultra-fast online stores like Shein and Boohoo make thousands a day, meant to be worn once or maybe twice then tossed into a landfill. The fashion industry is responsible for more greenhouse gases than international flights and maritime shipping combined. It also makes up a fifth of global plastics and trillions of microfibers: tiny plastic threads shed by clothing when laundered that have become one of the biggest threats to the ocean.

However, there are changes being proposed in the European Union to regulate the completely unregulated fashion industry. In the US, we can support the Fashion Act in New York State or the FABRIC Act in the U.S. Congress. The truth is, if we want to address climate change, we absolutely have to address the fashion industry.

2. Change is the only constant.

Ancient cultures rose and fell on color. For example, red was one of the foundations of the Spanish empire. When they were off marauding and colonizing they came across these bugs called cochineal in Central America. If you squished the females, you’d get one drop of pure durable, lightfast carmine, the most brilliant red that had ever been. It took hundreds of thousands of them to dye a pound of cloth. They were worth more than their weight in gold, and the Spanish kept the source of this color secret; nobody knew it was insects. Color could be cutthroat in those days. Blue was gaining popularity—indigo was more easily imported to Europe, which was affecting red’s profits. So the red merchants would bribe those who made stained glass windows for churches to make devils blue, so consumers would associate blue with hell and not buy it. But that didn’t work.

“Dyeing and finishing textiles is responsible for a fifth of the world’s industrial water pollution.”

It was in the 19th century that the whole thing collapsed. An eighteen-year-old college student at the Royal College of London was home for spring break trying to do an experiment that would impress his chemistry professor. There was a pinkish-purple residue in his test tube, so he wiped it out with a white cloth. When he went to wash the cloth, it wouldn’t wash out; without realizing it, he’d invented chemical dye. This first one was called mauve, and within fifteen years the natural dye industry had collapsed. All that money, all that knowledge, all that history, gone. Dye made of fossil fuel has had profound environmental implications of course, and dyeing and finishing textiles is responsible for a fifth of the world’s industrial water pollution.

As an aside, it’s a fascinating thing to look at this moment in history. The invention of chemical dye was another of those nothing-lasts-forever moments, when something that seemed so permanent, so eternal, just disappears almost overnight. In our time, the tech industry has bulldozed print newspapers, books, taxicabs, movie theaters, and maybe democracy. Meanwhile, there are the natural evolutions of life—children growing and leaving, parents dying, our own aging, fires and floods that alter landscapes. And there are pandemics, another reminder that change is our real constant and our greatest skill is our adaptability.

3. Let go of “is it good” and “does it suck?”

There’s an American cartoonist called Lynda Barry who wrote about how, as a child, she would draw in this freeform way, art just pouring out of her. At some point, she learned what she calls the “two questions”: “Is this good or does this suck?” These two questions are the death of creativity.

Likely, sometime in elementary school, you experience some moment of what educational psychologist Ronald Beghetto calls “creative mortification,” a phrase so evocative, it will carry you to your grave. When you are shamed or just too harshly critiqued for your efforts, you put down the pencil, paintbrush, baseball bat, test tube, violin, whatever it is, and you never do that thing you loved again. Mortification literally means, “to put to death.” The best defense against those psychologically lethal blows is to resist “good” and “bad” altogether and instead ask the questions, “What worked here?” or, “What might I do differently next time?” It’s recognizing that the gift of creativity is in the way it challenges you, allows you to make meaning, and enriches your life.

4. Ancient women’s work was always political.

In ancient times women spent an enormous amount of time spinning. They didn’t have the internet or TV so they would spin away the time telling each other these stories which were far bawdier before the brothers Grimm got ahold of them. Spinsters were unmarried women who were free from the demands of children or a husband. They were valuable contributors because they could spend more time spinning and it wasn’t a bad thing.

“There is a long, venerable history of using needlework as a political act.”

The industrial revolution took those tasks out of the home and along with it young women and teenage girls who, in reaction to the horrific conditions of the mills, launched the first labor strikes. Although unsuccessful, they did form the basis for the modern American labor movement and the American feminist movements. It’s no accident that years later we have young female voices—Greta Thunberg, X Gonzalez in Parkland (who is non-binary but grew up in a female body), or Malala Yousafzai. Teenage girls have always been our political voice, our conscience, and our leaders.

It’s also no accident that the first thing women did as an act of dissent when Trump was elected was knit. No matter how you feel about those pussyhats, there is a long, venerable history of using needlework as a political act. You’ve probably learned about the Boston Tea Party in school but did you learn about the importance of women’s boycott of British cloth and their public spinning bees in sparking the revolution? Did you learn that World War I was all but over after 75,000 troops had died of an epidemic of trench foot, caused by wet toes, until women on the home front saved the day, making socks by the millions? There are so many examples throughout history, here and abroad.

Today’s public knitters have mobilized against nuclear proliferation and the decimation of coral reefs. They have made blankets to welcome refugees, crafted tiny sweaters to save oil spill-damaged penguins, knitted “temperature scarves” to document climate change, stitched for racial justice, and sent handmade uteri to Congress in support of abortion rights. Do such acts of “craftivism” ultimately make a difference? Well, change starts with personal reflection, followed by connection to like-minded others, and, finally, engagement in repeated, targeted collective action. The conversations those projects inspire can jump-start that process, one stitch at a time.

5. Sing with your elders.

My mom had just died when I started this book, and my dad had dementia; he was in a facility in Minneapolis and I couldn’t visit him during the lockdown. It was hard to connect, he was hearing impaired, and often non-responsive, so talking on the phone was nearly impossible. But while doing these ancient arts, I could slow down. Especially when I was carding fleece.

When carding fleece, you use two things that look like dog brushes. You put a tiny bit on and brush back and forth to make it nice for spinning, then you roll it up into a puff and set it aside. It would take me ten minutes to make a puff and I read that you need 579 puffs for a sweater. While doing that incredibly tedious work, I’d sit with my dad on the hyper-modern technology of FaceTime and just be with him. He thought we were in the same room. He’d say “Peg can you hand me a glass of water?” and I’d say, “Dad I can’t reach it, you’ll have to get it yourself.” We would also sing because the part of the brain that stores lyrics is different from the part affected by dementia. We would sing “You Are My Sunshine,” “Give My Regards to Broadway” and others. My dad and I did not always have an easy relationship. He’s gone now, but I am so deeply grateful for that time we had together. It was one of the real gifts of the knitting process: slowing down enough to have the time together, to just love him, and to make our peace.

To listen to the audio version read by author Peggy Orenstein, download the Next Big Idea App today: