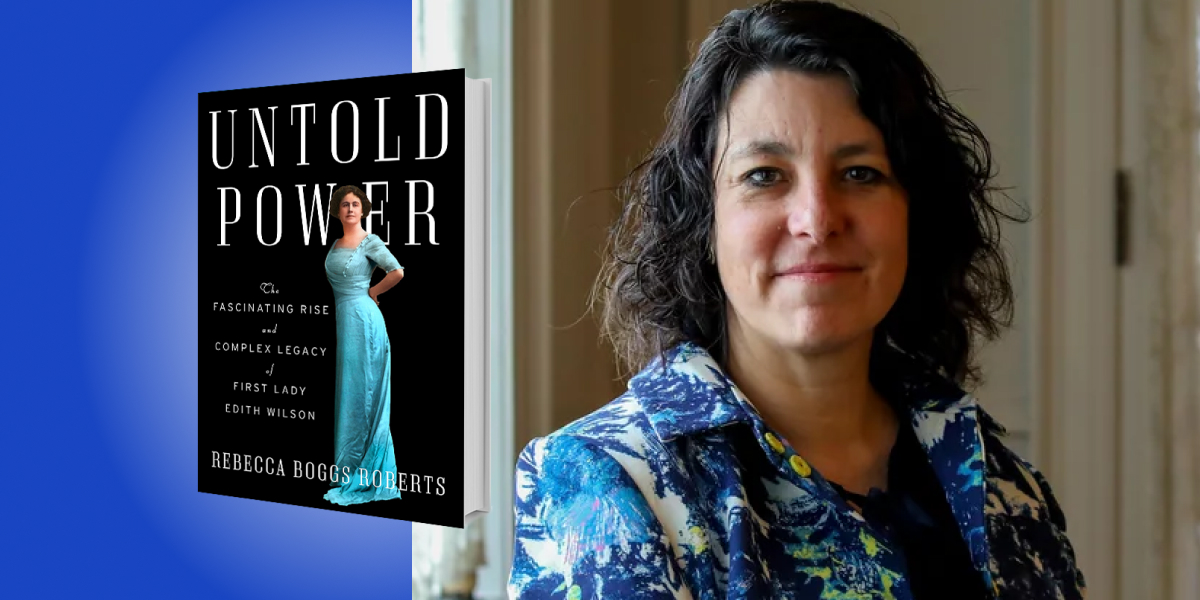

Rebecca Boggs Roberts is an award-winning educator, author, and speaker, and is a leading historian of American women’s suffrage and civic participation. She is currently deputy director of events at the Library of Congress and serves on the board of the National Archives Foundation, on the Council of Advisors of the Women’s Suffrage National Monument Foundation, and on the Editorial Advisory Committee of the White House Historical Association.

Below, Rebecca shares 5 key insights from her new book, Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson. Listen to the audio version—read by Rebecca herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. You can’t judge someone from just ten percent of their lives.

Edith became the first lady in 1915 when she married President Woodrow Wilson. The Wilsons stayed in the White House until 1921, when Warren and Florence Harding moved in. Edith had, of course, a life before and after her stint at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. But you can’t get the full picture of someone’s life from an isolated sliver.

If you know one thing about Edith Wilson, it is probably that in 1919, when Woodrow Wilson suffered a massive stroke, she secretly seized control of the executive branch and effectively acted as the nation’s president for months. This is true, and I don’t blame biographers for focusing on this chapter of her life—it is fascinating. But if you only look at that moment, Edith inevitably comes off as one of three stock characters: a naïve rube who was manipulated by savvy political men; a single-mindedly devoted wife who was thinking only of her husband, consequences be damned; or a Lady Macbeth who craved power for her own ambition and seized it when she saw her chance. None of these options are the whole truth, as no stock character can be.

If you are surprised by what Edith did in 1919, you know nothing of who she was before that moment when her husband collapsed. Throughout her life, she showed again and again that she was smart, confident, independent, unafraid to voice her opinion, and not overly invested in telling the truth. If you watched her before 1919—how she got out of her small Appalachian town to Washington DC, became the first woman in the city to get a driver’s license, ran a high-end, well-respected business, and traveled the world—you would have a much better sense of who she was and what she was capable of. That is, if you can find the right sources.

2. A person can be an unreliable narrator of her own life story.

Since no one was paying much attention to Edith Bolling Galt before she met the president in 1915, sometimes the only source for certain events is Edith’s memoir. The memoir itself is a delight—funny, frank, and full of personal details. She was the first first lady to write a memoir, and it became the must-read Washington book of 1939.

It is also, at times, demonstrably untrue. Edith claimed she began writing it in a fury, incensed at the version of events other members of the Wilson administration were publishing in their own memoirs. She claimed she was trying to set the record straight, but she was clearly trying to protect the version of events that put herself and her husband in the best possible light. More than once, she twisted the facts. Therefore, it’s risky to lean on her memoir as a source of truth, even for the years for which it is the only primary source available.

“She was the biggest disseminator of that version of herself.”

Beyond simple accuracy, Edith’s memoir needs to be filtered for a certain amount of myth-making. That dutiful wife stock character? The one where she was only thinking of her ailing husband, fighting for his very life, not at all interested in politics? She was the biggest disseminator of that version of herself. According to Edith’s memoir, the doctors came to her after Woodrow’s stroke and laid it out in stark terms: if her husband did his job, he would die. If he resigned, he would die, because ratifying the Treaty of Versailles and seeing the US join the League of Nations was all Woodrow was living for. Her only option, as she saw it, was to do his job for him until he improved enough to do it himself. What else could a devoted wife do? She did not apologize. She was fighting for her husband first, she said, and the needs of the nation had to take second place.

She also insisted that her “stewardship”, as she called it, was very brief since after the initial crisis had passed, her husband’s mind returned quickly to its characteristic razor sharpness. Some contemporaries dispute this fact and others corroborate it. But since Edith tightly controlled who saw the president, objective descriptions are hard to come by. Interestingly, the version of Edith as an apolitical woman, devoted only to the needs of her heroic husband, is undermined by her own words in another context.

3. Personal letters can be the best way to understand what someone was truly like.

Anything written for publication is curated for a broad audience. Private letters are curated for an audience of one. Throughout their courtship in 1915, Woodrow and Edith wrote to each other constantly. Of course, they certainly didn’t expect me to be reading their mail over a hundred years later. What do those letters reveal? For one, Woodrow Wilson was an over-the-top romantic. Truly. Professor Wilson, who cultivated an image of intellectual detachment, and moralistic to the point of priggishness, wrote absolutely gushy, even racy letters. He fell hard and fast for Edith and was not afraid to tell her so. He did not tease or crack wise, he simply, earnestly poured out his sincere devotion.

As for Edith, her letters are funny and gossipy and much less ardent. From the very beginning, she wanted to know all about the inner workings of politics. Woodrow first proposed to Edith only five weeks after they met. She initially turned him down. She thought it was too soon, but they agreed to keep seeing each other and get to know each other better. The next day, Woodrow wrote her a note extolling her wonderful loveliness and insisting his heart could not breathe without her. She wrote back, wondering what he really thought of William Jennings Bryan. Would he resign as secretary of state? If so, who would take his place? She even offered herself for the job. She was kidding—mostly—but again and again throughout their correspondence he would gush forth his fervor and she would bring the conversation back around to politics. She told him his second letter to Germany, after the sinking of the Lusitania, was not up to his usual standards. She did not think he was getting good advice from his friend Edward House. She pointedly did not tell him that he was perfect and wonderful in every way, and she was flattered just to be in his presence. Meanwhile, he admitted to her that he snuck into the Green Room while she attended a ladies tea at the White House, just so he could steal a glimpse of her lovely form through the lace curtains.

“Professor Wilson, who cultivated an image of intellectual detachment, and moralistic to the point of priggishness, wrote absolutely gushy, even racy letters.”

Finally, Woodrow caught on that policy analysis was a likelier path to Edith’s heart. He began to send, along with his love letters, big envelopes full of legislation and political correspondence. He taught her his personal cipher so she could decode messages from diplomats. She loved it. And eventually, she admitted that she loved him. So why did this astute, politically savvy woman cloak herself in the guise of the perfect wife with no interests outside of her husband’s welfare?

4. Sometimes women who make history have to pretend they didn’t make history.

For a very long time, women simply could not hold positions of power while being female. Even today, when women can hold public office or run large corporations or influence millions, they have to be careful not to be seen as too ambitious, abrasive, or shrill.

Edith grew up in Wytheville, Virginia at the end of the 19th century. Her mother and grandmother schooled her in the precepts of the Victorian-era cult of true womanhood—piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness. Edith’s self-confidence and strong opinions chafed against those ideals, but she still believed she should strive for them, or at least be seen to be striving for them. She had to strike the same bargains women throughout history have struck; make your own priorities look like someone else’s ideas. Accomplish what you can without taking credit for it. Wield “soft power” behind the scenes. Let a powerful man think of you as his secret weapon, instead of the agent of your own power.

Edith was totally complicit in the sexist minimization of her impact on American history. That was the only way she could make her actions, which, let’s be clear, were totally unconstitutional—no one elected Edith to anything—seem acceptable, even admirable. It’s one of the reasons women’s history is defined by so many untold stories. Sometimes it served the women best for their stories to remain untold.

Our hall-of-fame model of history, which lionizes great men who do great things, is not subtle enough to recognize that for most of history, women have wielded power differently than men, and have often covered their own tracks. It’s also not subtle enough to recognize that those great men weren’t always so great.

5. The hero/villain binary of historical narrative is wrong, boring, and destructive.

Very few people are purely saints or unrelenting sinners. We’re more complicated than that. People who accomplish big things and effect huge social change can still have flaws, make mistakes, and be slow to learn. Telling their full, complex stories does not take anything away from their impacts on history. Insisting on using an uncritical eye on historic figures is simply bad scholarship.

“Finding out that the people who have changed the world are flawed is liberating.”

Yet, there are still those who only want the heroic parts of our nations story to be told. That simplistic narrative is not only bad history, it’s pretty boring. Saints are kind of dull. I’d rather know that Alexander Hamilton was vain and insecure, and Abraham Lincoln suffered from depression, and Franklin Roosevelt hated being alone. It makes them much more interesting characters. Knowing those things about them doesn’t in any way change the fact that Hamilton revolutionized the nation’s finances, Lincoln saved the union, or Roosevelt led the nation through two of the greatest crises of the 20th century.

Edith Wilson was no saint. She was petty, bigoted, casual with the truth, and prone to holding grudges. She was also clever, funny, self-deprecating, and the absolute bedrock support of her large number of family and friends. The most momentous thing she did can be seen, depending on your perspective, as misguided, scheming, stupid, brilliant, naïve, or un-American, among many other adjectives.

Which brings up the other reason to present figures from history as real, three-dimensional people: we should be able to see ourselves in them. We should be able to judge whether we find them admirable. We should also feel empowered to make history ourselves. Finding out that the people who have changed the world are flawed is liberating. It means that all of us, with all our flaws, can change the world too, not just once-in-a-generation geniuses. Edith Bolling Galt Wilson was deeply flawed. But she was also totally fascinating.

To listen to the audio version read by author Rebecca Boggs Roberts, download the Next Big Idea App today: